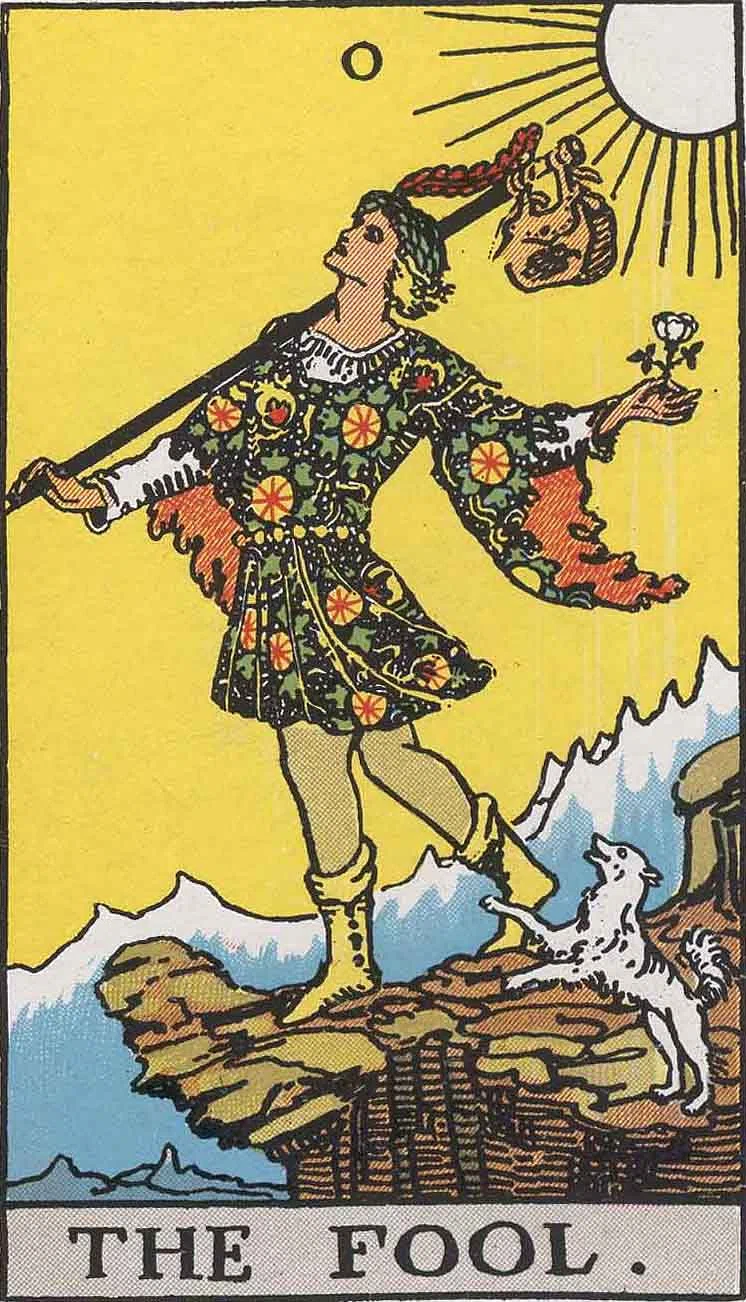

Last summer, while strolling down the main street of a secluded seaside town with friends, I stumbled upon a secondhand shop filled with witchcraft supplies. Intrigued, we decided to dive into the mysterious world of tarot reading. After several attempts at reading each other’s futures, we began to piece together (somewhat cohesive) narratives from the vivid symbolic imagery of the cards. It left me wondering—should people look to symbols like these for guidance? And more importantly, could they genuinely shape the choices we make in the future?

Last summer, while strolling down the main street of a secluded seaside town with friends, I stumbled upon a secondhand shop filled with witchcraft supplies. Intrigued, we decided to dive into the mysterious world of tarot reading. After several attempts at reading each other’s futures, we began to piece together (somewhat cohesive) narratives from the vivid symbolic imagery of the cards. It left me wondering—should people look to symbols like these for guidance? And more importantly, could they genuinely shape the choices we make in the future?

Symbols are everywhere, and they play a crucial role in how we think and communicate. They help us express complex ideas, make sense of the world, and understand things that might otherwise be too difficult to articulate. But how exactly have we come to understand symbols? Well, it all comes down to how our brains are wired. Whether it’s an object, a word, a sound, or even a living being, the brain identifies symbols through a system called resemblance-based representation (Williams & Collings, 2018). Our brains process all information in patterns, including symbols and their referents—the actual things that a word denotes. These patterns are not random; they share structural similarities that link symbols to their meanings. Take the heart symbol, for example. It represents the referent love, even though a heart isn’t literally love itself. People just learned to associate the two over time. This resemblance-based representation ties into how the brain processes and predicts the world. Rather than passively absorbing information, it actively compares new input to existing mental models formed by past experiences. Symbols, which resemble real-world objects or ideas, are quickly recognized and interpreted through these mental shortcuts, making predictions more efficient. This system helps us navigate the world effortlessly, showing how essential symbols are to understanding our surroundings. But this system of resemblance-based representation is more than just a tool for individual cognition. Symbols hold significant cultural weight, reflecting shared beliefs and values that shape the way entire societies perceive the world. Take white, for example. In the West, it’s a symbol of purity and cleanliness, while in parts of Asia, it’s traditionally worn at funerals to symbolize mourning. This was also the case in 16th-century France, where queens wore white to mourn—nothing says “grief” quite like a fancy white gown, right? Similarly, the snake is a symbol that takes on vastly different meanings across cultures. In Europe, it’s often linked to evil and temptation, rooted in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. But in India, it’s a symbol of protection and spiritual power, with a nice side gig as Shiva’s trusty neck accessory. My personal favourite culturally-contested symbol is the crossed-fingers. In Europe, it’s a symbol of luck, dating back to the 16th century, as it was believed to resemble a cross – a way to implore protection. In Vietnam, however, crossing fingers is considered very rude, as they believe it resembles female genitalia! All these examples show that the significance of symbols is far from static and can shift over time and across cultures, but whether their meanings are entirely arbitrary is still up for debate.

“Those who define symbols—governments, institutions, and dominant social groups—establish their meanings, shaping collective identity, values, and norms.”

Symbols are deeply rooted in human nature, unconsciously shaping thoughts and decisions beyond disputed cultural significance . Their power lies in their ability to evoke emotions, associations, and biases that influence behavior without individuals realizing it (Lizardo, 2016). Those who define symbols—governments, institutions, and dominant social groups—establish their meanings, shaping collective identity, values, and norms. However, once symbols gain cultural momentum, they operate independently, subtly guiding actions. For example, imagine walking into a polling station as an undecided voter and seeing the Union Jack prominently displayed. If you have a strong connection to the United Kingdom, the flag might evoke pride and belonging; if you don’t, it could create a sense of exclusion. In that moment, the flag is no longer just decoration—it becomes a subconscious cue that may influence your decision-making. Carl Jung offers a fascinating take on the power of symbols. While Freud focused on the personal unconscious, Jung proposed the concept of a collective unconscious, populated by universal archetypes. These include figures like The Hero, The Wise Old Man, and The Shadow—the latter representing the part of ourselves we’d rather not acknowledge. These archetypes show up across all cultures in myths, religions, and dreams, subconsciously shaping our decisions by tapping into emotions and impulses we might not fully understand. For instance, The Hero archetype often drives people to take risks or pursue challenges without fully realizing why. A soldier enlisting in the army may feel a deep sense of duty and purpose, not just because of personal beliefs but because society glorifies the Hero through myths, movies, and national narratives. This unconscious influence pushes individuals toward bravery even when the risks are high. Both Jung’s and Lizardo’s theories suggest that decision-making isn’t entirely rational; it’s shaped by deeply ingrained symbolic patterns. But could symbols also influence our conscious decisions? Symbols do more than passively influence behavior—they actively engage the conscious mind, prompting deliberate decision-making. Research suggests that symbols tied to moral values can act as deterrents to unethical behavior by increasing self-awareness (Desai & Kouchaki, 2017). Unlike subconscious cues, these symbols serve as reminders, encouraging individuals to reflect before they act. Consider the workplace. A study by Sreedhardi Desai and Maryam Kouchaki showed that a simple object—a cross necklace, an ethical slogan pinned to a board—might seem insignificant at first glance, but its presence has a tangible impact by heightening an individual’s awareness of their own values. The effect was even stronger for those who displayed such symbols themselves; wearing a visible sign of moral affiliation heightens personal accountability, making individuals more likely to consciously resist unethical demands.

“Symbols of authority, like a government seal, do not just passively suggest legitimacy—they make individuals actively assess the importance of a document before signing. In both cases, the symbol forces a moment of consideration, ensuring decisions are intentional rather than instinctive.”

Beyond morality, symbols can shape choices in more spontaneous ways. Some operate through the direct route of processing (Meis & Kashima, 2017), where universally recognized meanings lead to immediate but conscious decisions—such as stopping at a red sign. The danger symbol (⚠️) was actually designed with the intent of following universal design principles. The high contrast of yellow and black conventionally conveys caution, while the sharpness of the triangle signals our brain to be alert. Other symbols take an indirect route, requiring interpretation based on context and culture. For example, the rooster symbolizes national pride in France, but to someone outside that cultural framework, it would not evoke such feelings. Additionally, symbols play a key role in reinforcing social norms. A green recycling logo doesn’t simply trigger automatic behavior—it serves as a conscious prompt, reminding individuals of their environmental responsibility and encouraging a deliberate choice. Symbols of authority, like a government seal, do not just passively suggest legitimacy—they make individuals actively assess the importance of a document before signing. In both cases, the symbol forces a moment of consideration, ensuring decisions are intentional rather than instinctive. Ultimately, symbols don’t merely shape behavior; they guide our conscious navigation of the world. Whether it’s reinforcing moral accountability, encouraging social responsibility, or respecting authority, symbols demand our engagement, proving that while our choices are influenced, they remain ultimately our own. Does that mean we should rely on tarot cards for decision-making? Well, maybe—after all, they could reveal unconscious insights, according to Jung. But perhaps these symbols are simply there to remind us that it’s okay to lean on them in moments of uncertainty. After all, isn’t that how we’re wired?

References

Desai M. N. Kouchaki M. (2017). Moral symbols: a necklace of garlic against unethical requests. The Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 7–28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26157390

Jung C. G. (1934). Collected works of C.G. Jung, volume 9 (Part 1): archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhrnk

Lizardo O. (2016). Cultural symbols and social structures: The role of meaning in shaping behavior. Qualitative Sociology, 36(3), 199–204. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11133-016-9329-4.pdf

Meis J., & Kashima Y. (2017). Signage as a tool for behavioral change: Direct and indirect routes to understanding the meaning of a sign. Plos One,12(8), e0182975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182975

Williams D., & Colling L. (2018). From symbols to icons: the return of resemblance in the cognitive neuroscience revolution. Synthese, 195, 1941–1967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1578-6

Symbols are everywhere, and they play a crucial role in how we think and communicate. They help us express complex ideas, make sense of the world, and understand things that might otherwise be too difficult to articulate. But how exactly have we come to understand symbols? Well, it all comes down to how our brains are wired. Whether it’s an object, a word, a sound, or even a living being, the brain identifies symbols through a system called resemblance-based representation (Williams & Collings, 2018). Our brains process all information in patterns, including symbols and their referents—the actual things that a word denotes. These patterns are not random; they share structural similarities that link symbols to their meanings. Take the heart symbol, for example. It represents the referent love, even though a heart isn’t literally love itself. People just learned to associate the two over time. This resemblance-based representation ties into how the brain processes and predicts the world. Rather than passively absorbing information, it actively compares new input to existing mental models formed by past experiences. Symbols, which resemble real-world objects or ideas, are quickly recognized and interpreted through these mental shortcuts, making predictions more efficient. This system helps us navigate the world effortlessly, showing how essential symbols are to understanding our surroundings. But this system of resemblance-based representation is more than just a tool for individual cognition. Symbols hold significant cultural weight, reflecting shared beliefs and values that shape the way entire societies perceive the world. Take white, for example. In the West, it’s a symbol of purity and cleanliness, while in parts of Asia, it’s traditionally worn at funerals to symbolize mourning. This was also the case in 16th-century France, where queens wore white to mourn—nothing says “grief” quite like a fancy white gown, right? Similarly, the snake is a symbol that takes on vastly different meanings across cultures. In Europe, it’s often linked to evil and temptation, rooted in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. But in India, it’s a symbol of protection and spiritual power, with a nice side gig as Shiva’s trusty neck accessory. My personal favourite culturally-contested symbol is the crossed-fingers. In Europe, it’s a symbol of luck, dating back to the 16th century, as it was believed to resemble a cross – a way to implore protection. In Vietnam, however, crossing fingers is considered very rude, as they believe it resembles female genitalia! All these examples show that the significance of symbols is far from static and can shift over time and across cultures, but whether their meanings are entirely arbitrary is still up for debate.

“Those who define symbols—governments, institutions, and dominant social groups—establish their meanings, shaping collective identity, values, and norms.”

Symbols are deeply rooted in human nature, unconsciously shaping thoughts and decisions beyond disputed cultural significance . Their power lies in their ability to evoke emotions, associations, and biases that influence behavior without individuals realizing it (Lizardo, 2016). Those who define symbols—governments, institutions, and dominant social groups—establish their meanings, shaping collective identity, values, and norms. However, once symbols gain cultural momentum, they operate independently, subtly guiding actions. For example, imagine walking into a polling station as an undecided voter and seeing the Union Jack prominently displayed. If you have a strong connection to the United Kingdom, the flag might evoke pride and belonging; if you don’t, it could create a sense of exclusion. In that moment, the flag is no longer just decoration—it becomes a subconscious cue that may influence your decision-making. Carl Jung offers a fascinating take on the power of symbols. While Freud focused on the personal unconscious, Jung proposed the concept of a collective unconscious, populated by universal archetypes. These include figures like The Hero, The Wise Old Man, and The Shadow—the latter representing the part of ourselves we’d rather not acknowledge. These archetypes show up across all cultures in myths, religions, and dreams, subconsciously shaping our decisions by tapping into emotions and impulses we might not fully understand. For instance, The Hero archetype often drives people to take risks or pursue challenges without fully realizing why. A soldier enlisting in the army may feel a deep sense of duty and purpose, not just because of personal beliefs but because society glorifies the Hero through myths, movies, and national narratives. This unconscious influence pushes individuals toward bravery even when the risks are high. Both Jung’s and Lizardo’s theories suggest that decision-making isn’t entirely rational; it’s shaped by deeply ingrained symbolic patterns. But could symbols also influence our conscious decisions? Symbols do more than passively influence behavior—they actively engage the conscious mind, prompting deliberate decision-making. Research suggests that symbols tied to moral values can act as deterrents to unethical behavior by increasing self-awareness (Desai & Kouchaki, 2017). Unlike subconscious cues, these symbols serve as reminders, encouraging individuals to reflect before they act. Consider the workplace. A study by Sreedhardi Desai and Maryam Kouchaki showed that a simple object—a cross necklace, an ethical slogan pinned to a board—might seem insignificant at first glance, but its presence has a tangible impact by heightening an individual’s awareness of their own values. The effect was even stronger for those who displayed such symbols themselves; wearing a visible sign of moral affiliation heightens personal accountability, making individuals more likely to consciously resist unethical demands.

“Symbols of authority, like a government seal, do not just passively suggest legitimacy—they make individuals actively assess the importance of a document before signing. In both cases, the symbol forces a moment of consideration, ensuring decisions are intentional rather than instinctive.”

Beyond morality, symbols can shape choices in more spontaneous ways. Some operate through the direct route of processing (Meis & Kashima, 2017), where universally recognized meanings lead to immediate but conscious decisions—such as stopping at a red sign. The danger symbol (⚠️) was actually designed with the intent of following universal design principles. The high contrast of yellow and black conventionally conveys caution, while the sharpness of the triangle signals our brain to be alert. Other symbols take an indirect route, requiring interpretation based on context and culture. For example, the rooster symbolizes national pride in France, but to someone outside that cultural framework, it would not evoke such feelings. Additionally, symbols play a key role in reinforcing social norms. A green recycling logo doesn’t simply trigger automatic behavior—it serves as a conscious prompt, reminding individuals of their environmental responsibility and encouraging a deliberate choice. Symbols of authority, like a government seal, do not just passively suggest legitimacy—they make individuals actively assess the importance of a document before signing. In both cases, the symbol forces a moment of consideration, ensuring decisions are intentional rather than instinctive. Ultimately, symbols don’t merely shape behavior; they guide our conscious navigation of the world. Whether it’s reinforcing moral accountability, encouraging social responsibility, or respecting authority, symbols demand our engagement, proving that while our choices are influenced, they remain ultimately our own. Does that mean we should rely on tarot cards for decision-making? Well, maybe—after all, they could reveal unconscious insights, according to Jung. But perhaps these symbols are simply there to remind us that it’s okay to lean on them in moments of uncertainty. After all, isn’t that how we’re wired?