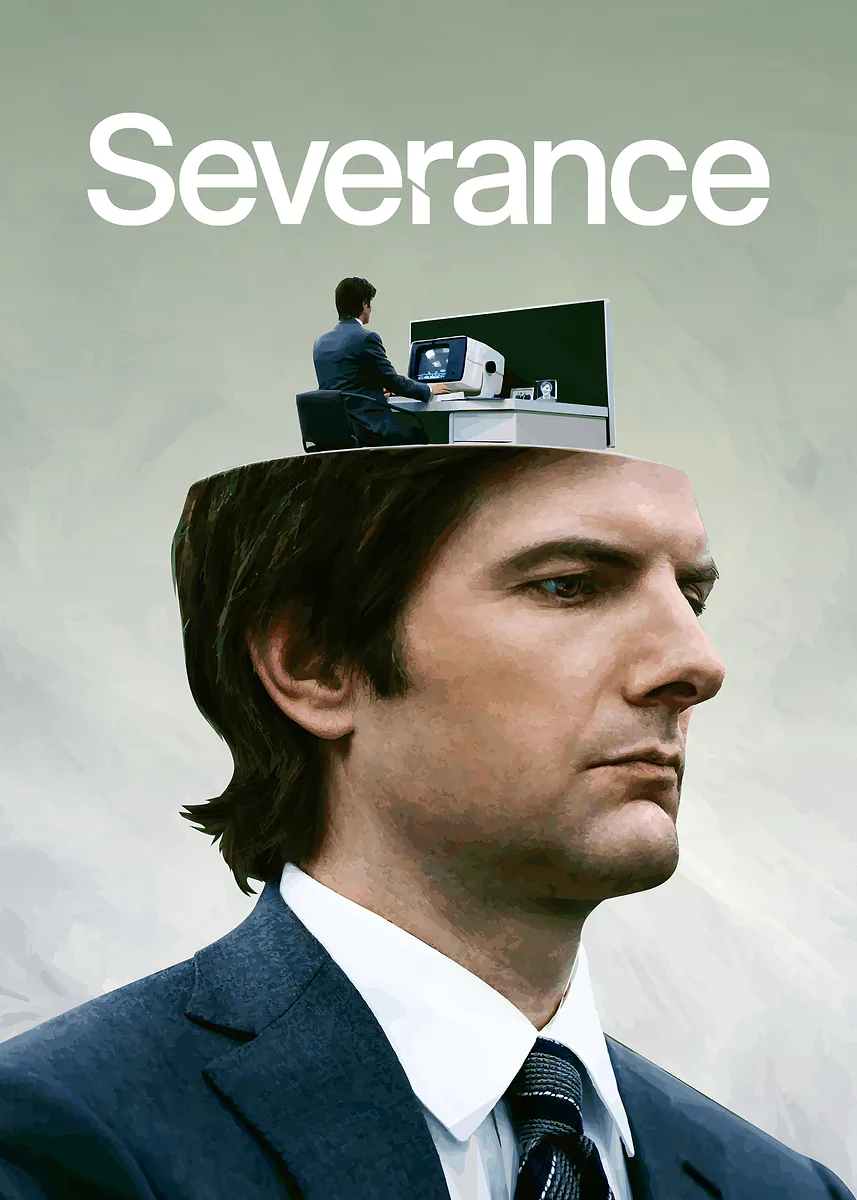

The critically acclaimed TV series Severance (2022) tells the story of four workers in the company Lumon Industries who had their brain surgically “severed”, which means their “work brain” and “personal life brain” have been separated: the workers lose all their personal memories and retrieve their work memories as soon as they step into their department at work; the opposite happens once they leave work. In other words, their episodic memory is split. The brilliance behind this show lies mainly in two aspects: the philosophical and morally charged subtext and the cinematography and visual design.

Who are we without our memories? Does our personality depend on them? By splitting our memory, would we technically be creating another person, with another life experience and with another consciousness? These are just some of the questions that this show poses through its strong psychological and philosophical theme. One of the biggest topics in Severance is identity and its relation to memory. In the series it is said that if you quit your job, you would be killing yourself in a way, since you would end your consciousness as you know it. If the workers quit, they wouldn’t be able to go back to their department, so they would never be able to access the episodic memory of the “innie” (i.e. the self or consciousness of the person when they’re at work, as opposed to “outie”, when they are outside of work). This also brings up more ethical questions about the work scenario: isn’t it unethical to have the workers in the office continuously forever without seeing the outside world? Never seeing nature, other humans, having the chance to fall in love or have kids. Are they not slaves in a sense?

Following this train of thought, there is also a strong political and societal theme: the interplay between the oppressors and the oppressed in this fight for liberty. Are we really in control of our lives or are we just being led to think we are? Severance explores the concept of freedom, and how the lack of it affects us. Hell is mentioned several times in the series, making reference to how being trapped and having no real freewill is directly comparable to being in hell. The situation becomes inescapable because if your “outie” decides that you have to keep working, then there is nothing you can do about it: there is no way of getting messages in or out of the office and not even suicide attempts will work.

The storyline holds a strong similarity to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, where the characters live in blissful ignorance, looking at the shadows Lumon projects on the wall for them, living their lives every day without knowing what these shadows are or who projects them. However, everything changes when one of the workers, Helly R., starts fighting to break the chains that hold her down to make it out of that basement and see the light, that is, discovering the truth about who they are and what Lumon is truly doing.

“I guess this is the part where I should tell you to go to Hell, except you’re already here”. “The good news is, Hell is just a product of a morbid, human imagination. The bad news is whatever humans can imagine, they can usually create”.

A strong theme is also corporate cults: the founder of Lumon Industries is praised like a God, and the employees never even see or talk to the board of the company. Additionally, the four members of MDR (macro data refinement) have no idea what their work truly does or what they’re working towards, they just know that it is “mysterious and important”. This creates a mystic religion around the company, which is a factor that serves as another unethical manipulation that prevent the workers from leaving: if you leave, you turn your back on your religion, on your beliefs.

The design of the office is also important to highlight. The sterile and maze-like hallways remind us that the characters can’t escape where they are. They don’t really know where they are or why they are there, and no matter which direction they choose to go, in the end they are not the ones controlling the direction in which their life is moving, their “outie” is. The MDR room is huge, with only four merged cubicles in the middle. The excessive space surrounding the cubicles symbolizes how isolated the characters feel from the outside world, but also distant from each other, with screens dividing them.

Lastly, Severance has a brutally refreshing cinematography. Compared to other shows currently airing, Severance has a very clear and infrequently seen aesthetic: bright office lights that contrast with deep shadows, minimalistic scene decoration, etc. The aesthetic is not only strong and unique, but also meaningful and intentional. The predominantly white backgrounds and the recurring shots where we see the characters through narrow spaces represent the characters’ situation: a lack of knowledge and liberty and isolation from the outside world. The camera is almost always steady and moved automatically, with the camera being hand-held only when there is conflict between the “innies” and their supervisors. Outside of Lumon, we see much softer use of lights as well as a less rigid camera manoeuvring. Furthermore, we see creative and eye-catching use of camera techniques, such as the iconic plain background Dolly-zoom used to create the illusion of the change between the “innie” to the “outie” and the other way around by slightly modifying the characters’ face.

Severance’s themes and aesthetics are truly refreshing for current TV media; in a panorama where everything seems to be recycled and where police crime and sitcoms reign, a series that is intellectually and ethically challenging feels like a breath of fresh air.

- Directors: Ben Stiller, Aoife McArdle, Uta Briesewitz, Sam Donovan, and Jessica Lee Gagné.

Severance is currently available for streaming on Apple TV.

The critically acclaimed TV series Severance (2022) tells the story of four workers in the company Lumon Industries who had their brain surgically “severed”, which means their “work brain” and “personal life brain” have been separated: the workers lose all their personal memories and retrieve their work memories as soon as they step into their department at work; the opposite happens once they leave work. In other words, their episodic memory is split. The brilliance behind this show lies mainly in two aspects: the philosophical and morally charged subtext and the cinematography and visual design.

Who are we without our memories? Does our personality depend on them? By splitting our memory, would we technically be creating another person, with another life experience and with another consciousness? These are just some of the questions that this show poses through its strong psychological and philosophical theme. One of the biggest topics in Severance is identity and its relation to memory. In the series it is said that if you quit your job, you would be killing yourself in a way, since you would end your consciousness as you know it. If the workers quit, they wouldn’t be able to go back to their department, so they would never be able to access the episodic memory of the “innie” (i.e. the self or consciousness of the person when they’re at work, as opposed to “outie”, when they are outside of work). This also brings up more ethical questions about the work scenario: isn’t it unethical to have the workers in the office continuously forever without seeing the outside world? Never seeing nature, other humans, having the chance to fall in love or have kids. Are they not slaves in a sense?

Following this train of thought, there is also a strong political and societal theme: the interplay between the oppressors and the oppressed in this fight for liberty. Are we really in control of our lives or are we just being led to think we are? Severance explores the concept of freedom, and how the lack of it affects us. Hell is mentioned several times in the series, making reference to how being trapped and having no real freewill is directly comparable to being in hell. The situation becomes inescapable because if your “outie” decides that you have to keep working, then there is nothing you can do about it: there is no way of getting messages in or out of the office and not even suicide attempts will work.

The storyline holds a strong similarity to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, where the characters live in blissful ignorance, looking at the shadows Lumon projects on the wall for them, living their lives every day without knowing what these shadows are or who projects them. However, everything changes when one of the workers, Helly R., starts fighting to break the chains that hold her down to make it out of that basement and see the light, that is, discovering the truth about who they are and what Lumon is truly doing.

“I guess this is the part where I should tell you to go to Hell, except you’re already here”. “The good news is, Hell is just a product of a morbid, human imagination. The bad news is whatever humans can imagine, they can usually create”.

A strong theme is also corporate cults: the founder of Lumon Industries is praised like a God, and the employees never even see or talk to the board of the company. Additionally, the four members of MDR (macro data refinement) have no idea what their work truly does or what they’re working towards, they just know that it is “mysterious and important”. This creates a mystic religion around the company, which is a factor that serves as another unethical manipulation that prevent the workers from leaving: if you leave, you turn your back on your religion, on your beliefs.

The design of the office is also important to highlight. The sterile and maze-like hallways remind us that the characters can’t escape where they are. They don’t really know where they are or why they are there, and no matter which direction they choose to go, in the end they are not the ones controlling the direction in which their life is moving, their “outie” is. The MDR room is huge, with only four merged cubicles in the middle. The excessive space surrounding the cubicles symbolizes how isolated the characters feel from the outside world, but also distant from each other, with screens dividing them.

Lastly, Severance has a brutally refreshing cinematography. Compared to other shows currently airing, Severance has a very clear and infrequently seen aesthetic: bright office lights that contrast with deep shadows, minimalistic scene decoration, etc. The aesthetic is not only strong and unique, but also meaningful and intentional. The predominantly white backgrounds and the recurring shots where we see the characters through narrow spaces represent the characters’ situation: a lack of knowledge and liberty and isolation from the outside world. The camera is almost always steady and moved automatically, with the camera being hand-held only when there is conflict between the “innies” and their supervisors. Outside of Lumon, we see much softer use of lights as well as a less rigid camera manoeuvring. Furthermore, we see creative and eye-catching use of camera techniques, such as the iconic plain background Dolly-zoom used to create the illusion of the change between the “innie” to the “outie” and the other way around by slightly modifying the characters’ face.

Severance’s themes and aesthetics are truly refreshing for current TV media; in a panorama where everything seems to be recycled and where police crime and sitcoms reign, a series that is intellectually and ethically challenging feels like a breath of fresh air.

- Directors: Ben Stiller, Aoife McArdle, Uta Briesewitz, Sam Donovan, and Jessica Lee Gagné.

Severance is currently available for streaming on Apple TV.