On a quiet Sunday morning in August 1971, a city police car swept through the streets of West New York, arresting twenty-four male college students from their dormitories for armed robbery and vandalism. As curious neighbours looked on, each student was searched, handcuffed, and thrown into the back of a police car that drove them to a station. Here, they were booked for crime, blindfolded, and then herded into a basement that looked much like a detention cell.

On a quiet Sunday morning in August 1971, a city police car swept through the streets of West New York, arresting twenty-four male college students from their dormitories for armed robbery and vandalism. As curious neighbours looked on, each student was searched, handcuffed, and thrown into the back of a police car that drove them to a station. Here, they were booked for crime, blindfolded, and then herded into a basement that looked much like a detention cell.

Photo by Hans Reniers

Years later, in 1973, a news report revealed that these students had previously volunteered for a study on “prison life” at a basement in Stanford University’s Jordan Hall. They did not know the police were going to arrest them; while they may have at one point assumed that this had some connection to the experiment they had signed up for, none of them could be fully sure. It was this uncertainty – the question of whether what was happening to them was reality or an illusion – that Phillip Zimbardo, the lead researcher at Stanford, claimed to employ throughout his study. The participants, half assigned the role of “prisoners” and the other half “guards”, became so wholly immersed in their roles, that what started as an investigation of interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison quickly escalated into unexpectedly aggressive, abusive, and often pathological interactions between the participants (Haney et al., 1973). To everyone’s surprise, what was supposed to be a two-week study had to be shut down on the sixth day.

Ever since, the Stanford Prison Experiment has been the subject of countless research, commentary articles, news reports, and documentaries, discussing its enduring controversy as one of the most “dangerous” studies ever conducted (Jarrett, 2014). Open any psychology 101 textbook, and you will likely find Zimbardo and his colleagues cited in the chapter on social dynamics and conformity. Such is the nature of research that has never been done before – no matter how dramatic and disturbing the outcome, its cultural and psychological impact is felt decades later.

In the medical and health sciences, it is often believed that innovation requires risk-taking. Research on high-priority treatments for cancer, for example, involves risks for both researchers and participants involved in clinical trials, owing to the inherent uncertainties of a new drug and the potential for unintended, sometimes deadly, side effects. Life scientists always run the risk of new pathogens accidentally “escaping” a highly-controlled lab environment (e.g., take the hotly debated origin of SARS-Cov-2 that kickstarted the COVID-19 pandemic). Before any vaccines are rolled out to combat said pandemic, they undergo rigorous, repeated testing to ensure they do not cause more harm than good. Research continues in spite of these risks because it entails significant rewards, i.e, scientific and medical advancement.

“How best can they strike a balance between designing novel, high-risk studies and ensuring that they meet the ethical and methodological standards of good research? ”

On the other hand, how rewarding is it to pursue “risky” research in the social and behavioural sciences? For example, certain groups may be more “at-risk” for developing a mental disorder than others, like political refugees, delinquent youth and criminals, substance use victims, or institutionalised children. Conducting research with such sensitive populations is critical to driving individual, societal, and policy change, but requires special moral and legal consideration. Risky research isn’t problematic inherently – but it becomes so when not matched by proportional ethical rigour.

So let us think back, for a moment, to the strange dichotomy of the Stanford Prison Experiment: while Zimbardo designed an innovative, never-before-seen experiment, the sheer lack of ethical safeguards led to its very downfall. If the study were to be conducted today, years later, would researchers be better at ensuring risky research follows responsible research practices?

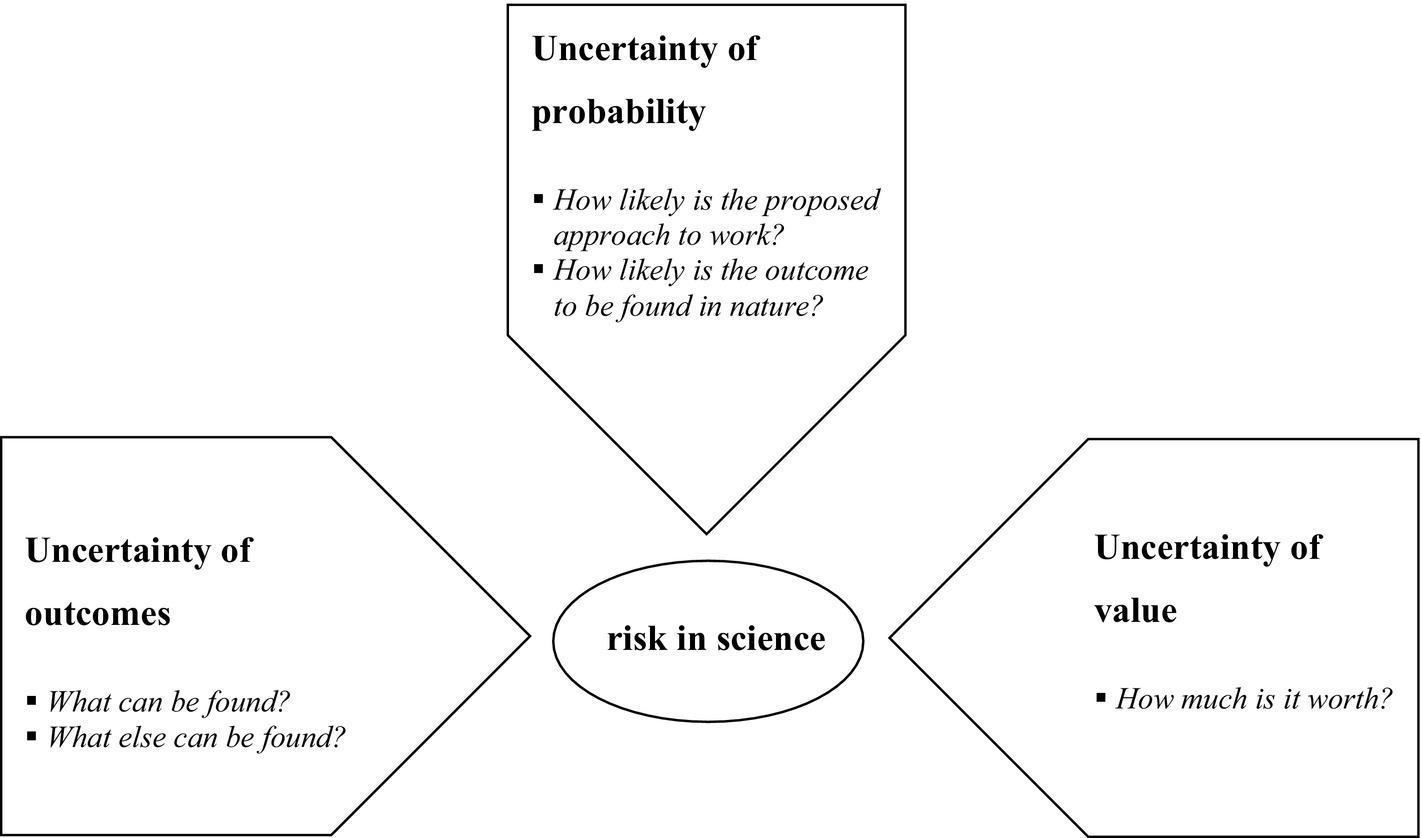

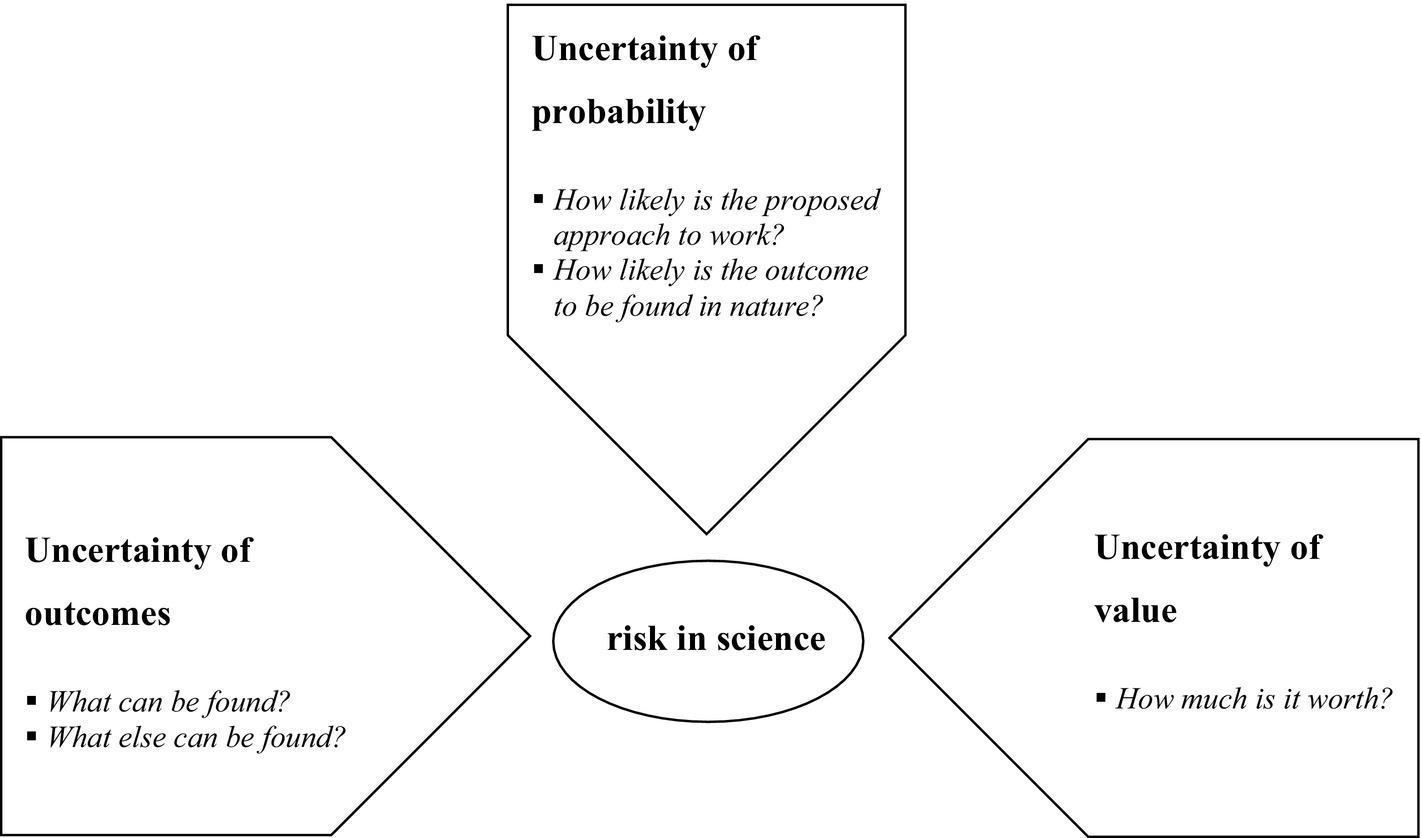

One may argue that all scientific research is inherently risky. But recognising which kind of risk – ethical, methodological, financial, or societal – is being undertaken allows researchers to tailor their process for maintaining this balance. Franzoni and Stephan (2023) provide a unique framework to think about some possible areas of risk. They call these components or sources of uncertainty in science, of which they discuss three main types: 1) uncertainty concerning the outcomes; 2) uncertainty concerning the probability of discovery, and 3) uncertainty concerning the value of the outcome.

From Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. (2023). Uncertainty and risk-taking in science: Meaning, measurement and management in peer review of research proposals. Research Policy, 52(3), 104706.

Here, we discuss these components using our initial example of the Stanford Prison experiment (note that the original framework was modelled on biomedical science research, so a direct translation to psychological research is tentative at best).

Uncertainty of outcomes. This concerns all the possible uncertainties about the world that the study can uncover. It begs the primary question, “What can be found?” The range of this question is larger in exploratory research on unknown phenomena. The Stanford Prison Experiment was a largely exploratory study where Zimbardo and his colleagues set out to find how people conform to social roles and norms, particularly in hierarchical structures like a prison. A secondary question could be, “What else can be found?” In this case, would Zimbardo’s (or any other researcher’s) presence as an authority figure influence how aggressively the guards acted? Here, the secondary finding is not merely an accidental by-product of the study, but raises broader questions about authority and obedience, and how they interact in a social dynamics framework.

Uncertainty of probability. Probability here refers to the likelihood of whether the study produces a certain outcome. How likely is the chosen method or approach to work (methodological uncertainty)? In a simulated prison, it is uncertain whether the guards and prisoners would naturally adopt their assigned roles, or if they would do so because they know they are being observed as part of an experiment. Moreover, how likely is the same outcome to be found in nature, i.e., the real world (natural uncertainty)? Some researchers have criticised the “theatrical design” of the Stanford experiment (Le Texier, 2019; Scott-Bottoms, 2024): given that everyone was playing a “role”, it is debatable whether interpersonal relations in a real prison play out similarly.

Uncertainty of value. Several times while designing a research proposal, authors may wonder, “How much is this outcome worth?” After all, the potential value of a study motivates fundraising strategies and subsequently, funding decisions. Evaluating scientific and societal impact involves taking stock of the current body of knowledge and how much a new outcome would contribute to it. For example, the Stanford Prison Experiment, despite its criticisms and controversies, has been influential in psychological research and continues to be taught in schools as part of social psychology curricula. One may wonder, did Zimbardo and colleagues see this coming?

Each of these risk components can be balanced with a safeguard: researchers can pre-register their study, identifying both their hypotheses and ethical “red lines” – conditions under which the study must be stopped if certain outcomes manifest. Simulation-based studies, like Zimbardo’s, are best complimented by debriefings to mitigate any adverse psychological impact of the experiment. Finally, a study’s value is enhanced when risk-taking follows responsibility, and is diminished if it comes at too high a psychological or social cost.

Beyond the ambit of subject matter and research design, how responsible can a risky researcher be? How best can they strike a balance between designing novel, high-risk studies and ensuring that they meet the ethical and methodological standards of good research?

These are conceptual questions with no direct answers. Nevertheless, there seems to be something about risky research that makes headlines, sparks controversy or debate, and elicits equal parts awe and criticism. Risky science tests the boundaries of what humans are capable of knowing and doing. But we know now, from the Stanford Prison Experiment, how easy it is to end up with unexpected displays of cruelty and dehumanisation. It is good to remember, in our pursuit of groundbreaking research and innovation, that every bold idea carries the burden of responsible execution.

References

- Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1, 69-97. http://pdf.prisonexp.org/ijcp1973.pdf

- Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. (2023). Uncertainty and risk-taking in science: Meaning, measurement and management in peer review of research proposals. Research Policy, 52(3), 104706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104706

- Jarrett, C. (2014). The 10 Most Controversial Psychology Studies Ever Published. The British Psychological Society. Retrieved January 1, 2025, from https://www.bps.org.uk/research-digest/10-most-controversial-psychology-studies-ever-published

- Stanford University Libraries (1971). Stanford Prison Experiment: transcripts. In Stanford University Libraries. Stanford University. Retrieved January 1, 2025, from https://exhibits.stanford.edu/spe/browse/transcripts

- Halzen, F., & Learned, J. G. (1988). High energy neutrino detection in deep polar ice (No. MAD-PH-428).

- Le Texier, T. (2019). Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment. The American psychologist, 74(7), 823–839. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000401

- Scott-Bottoms, S. (2024). Making a Drama out of a Crisis: The Curious Case of the Stanford Prison Study. University of Michigan Press. https://press.umich.edu/Blog/2024/04/Making-a-Drama-out-of-a-Crisis-The-Curious-Case-of-the-Stanford-Prison-Study

Years later, in 1973, a news report revealed that these students had previously volunteered for a study on “prison life” at a basement in Stanford University’s Jordan Hall. They did not know the police were going to arrest them; while they may have at one point assumed that this had some connection to the experiment they had signed up for, none of them could be fully sure. It was this uncertainty – the question of whether what was happening to them was reality or an illusion – that Phillip Zimbardo, the lead researcher at Stanford, claimed to employ throughout his study. The participants, half assigned the role of “prisoners” and the other half “guards”, became so wholly immersed in their roles, that what started as an investigation of interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison quickly escalated into unexpectedly aggressive, abusive, and often pathological interactions between the participants (Haney et al., 1973). To everyone’s surprise, what was supposed to be a two-week study had to be shut down on the sixth day.

Ever since, the Stanford Prison Experiment has been the subject of countless research, commentary articles, news reports, and documentaries, discussing its enduring controversy as one of the most “dangerous” studies ever conducted (Jarrett, 2014). Open any psychology 101 textbook, and you will likely find Zimbardo and his colleagues cited in the chapter on social dynamics and conformity. Such is the nature of research that has never been done before – no matter how dramatic and disturbing the outcome, its cultural and psychological impact is felt decades later.

In the medical and health sciences, it is often believed that innovation requires risk-taking. Research on high-priority treatments for cancer, for example, involves risks for both researchers and participants involved in clinical trials, owing to the inherent uncertainties of a new drug and the potential for unintended, sometimes deadly, side effects. Life scientists always run the risk of new pathogens accidentally “escaping” a highly-controlled lab environment (e.g., take the hotly debated origin of SARS-Cov-2 that kickstarted the COVID-19 pandemic). Before any vaccines are rolled out to combat said pandemic, they undergo rigorous, repeated testing to ensure they do not cause more harm than good. Research continues in spite of these risks because it entails significant rewards, i.e, scientific and medical advancement.

“How best can they strike a balance between designing novel, high-risk studies and ensuring that they meet the ethical and methodological standards of good research? ”

On the other hand, how rewarding is it to pursue “risky” research in the social and behavioural sciences? For example, certain groups may be more “at-risk” for developing a mental disorder than others, like political refugees, delinquent youth and criminals, substance use victims, or institutionalised children. Conducting research with such sensitive populations is critical to driving individual, societal, and policy change, but requires special moral and legal consideration. Risky research isn’t problematic inherently – but it becomes so when not matched by proportional ethical rigour.

So let us think back, for a moment, to the strange dichotomy of the Stanford Prison Experiment: while Zimbardo designed an innovative, never-before-seen experiment, the sheer lack of ethical safeguards led to its very downfall. If the study were to be conducted today, years later, would researchers be better at ensuring risky research follows responsible research practices?

One may argue that all scientific research is inherently risky. But recognising which kind of risk – ethical, methodological, financial, or societal – is being undertaken allows researchers to tailor their process for maintaining this balance. Franzoni and Stephan (2023) provide a unique framework to think about some possible areas of risk. They call these components or sources of uncertainty in science, of which they discuss three main types: 1) uncertainty concerning the outcomes; 2) uncertainty concerning the probability of discovery, and 3) uncertainty concerning the value of the outcome.

From Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. (2023). Uncertainty and risk-taking in science: Meaning, measurement and management in peer review of research proposals. Research Policy, 52(3), 104706.

Here, we discuss these components using our initial example of the Stanford Prison experiment (note that the original framework was modelled on biomedical science research, so a direct translation to psychological research is tentative at best).

Uncertainty of outcomes. This concerns all the possible uncertainties about the world that the study can uncover. It begs the primary question, “What can be found?” The range of this question is larger in exploratory research on unknown phenomena. The Stanford Prison Experiment was a largely exploratory study where Zimbardo and his colleagues set out to find how people conform to social roles and norms, particularly in hierarchical structures like a prison. A secondary question could be, “What else can be found?” In this case, would Zimbardo’s (or any other researcher’s) presence as an authority figure influence how aggressively the guards acted? Here, the secondary finding is not merely an accidental by-product of the study, but raises broader questions about authority and obedience, and how they interact in a social dynamics framework.

Uncertainty of probability. Probability here refers to the likelihood of whether the study produces a certain outcome. How likely is the chosen method or approach to work (methodological uncertainty)? In a simulated prison, it is uncertain whether the guards and prisoners would naturally adopt their assigned roles, or if they would do so because they know they are being observed as part of an experiment. Moreover, how likely is the same outcome to be found in nature, i.e., the real world (natural uncertainty)? Some researchers have criticised the “theatrical design” of the Stanford experiment (Le Texier, 2019; Scott-Bottoms, 2024): given that everyone was playing a “role”, it is debatable whether interpersonal relations in a real prison play out similarly.

Uncertainty of value. Several times while designing a research proposal, authors may wonder, “How much is this outcome worth?” After all, the potential value of a study motivates fundraising strategies and subsequently, funding decisions. Evaluating scientific and societal impact involves taking stock of the current body of knowledge and how much a new outcome would contribute to it. For example, the Stanford Prison Experiment, despite its criticisms and controversies, has been influential in psychological research and continues to be taught in schools as part of social psychology curricula. One may wonder, did Zimbardo and colleagues see this coming?

Each of these risk components can be balanced with a safeguard: researchers can pre-register their study, identifying both their hypotheses and ethical “red lines” – conditions under which the study must be stopped if certain outcomes manifest. Simulation-based studies, like Zimbardo’s, are best complimented by debriefings to mitigate any adverse psychological impact of the experiment. Finally, a study’s value is enhanced when risk-taking follows responsibility, and is diminished if it comes at too high a psychological or social cost.

Beyond the ambit of subject matter and research design, how responsible can a risky researcher be? How best can they strike a balance between designing novel, high-risk studies and ensuring that they meet the ethical and methodological standards of good research?

These are conceptual questions with no direct answers. Nevertheless, there seems to be something about risky research that makes headlines, sparks controversy or debate, and elicits equal parts awe and criticism. Risky science tests the boundaries of what humans are capable of knowing and doing. But we know now, from the Stanford Prison Experiment, how easy it is to end up with unexpected displays of cruelty and dehumanisation. It is good to remember, in our pursuit of groundbreaking research and innovation, that every bold idea carries the burden of responsible execution.

References

- Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1, 69-97. http://pdf.prisonexp.org/ijcp1973.pdf

- Franzoni, C., & Stephan, P. (2023). Uncertainty and risk-taking in science: Meaning, measurement and management in peer review of research proposals. Research Policy, 52(3), 104706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104706

- Jarrett, C. (2014). The 10 Most Controversial Psychology Studies Ever Published. The British Psychological Society. Retrieved January 1, 2025, from https://www.bps.org.uk/research-digest/10-most-controversial-psychology-studies-ever-published

- Stanford University Libraries (1971). Stanford Prison Experiment: transcripts. In Stanford University Libraries. Stanford University. Retrieved January 1, 2025, from https://exhibits.stanford.edu/spe/browse/transcripts

- Halzen, F., & Learned, J. G. (1988). High energy neutrino detection in deep polar ice (No. MAD-PH-428).

- Le Texier, T. (2019). Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment. The American psychologist, 74(7), 823–839. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000401

- Scott-Bottoms, S. (2024). Making a Drama out of a Crisis: The Curious Case of the Stanford Prison Study. University of Michigan Press. https://press.umich.edu/Blog/2024/04/Making-a-Drama-out-of-a-Crisis-The-Curious-Case-of-the-Stanford-Prison-Study