The year is 2025. You can sit at a café and take a machine learning course from Stanford, learn graphic design from YouTube, or even obtain a Google Data Analytics certificate from your bedroom. With the rise of online learning platforms, what is the point of universities anymore?

The year is 2025. You can sit at a café and take a machine learning course from Stanford, learn graphic design from YouTube, or even obtain a Google Data Analytics certificate from your bedroom. With the rise of online learning platforms, what is the point of universities anymore?

Platforms like Coursera, edX, and Khan Academy offer high-quality courses at a much lower cost than tuition-based education, sometimes even for free. They’re also highly flexible, since they are done online and at your own pace. Whether it is programming, marketing, psychology, or design, they can all be learned without ever stepping foot into a classroom. In terms of raw efficiency and accessibility, online platforms have the potential to outperform traditional education. So why haven’t we made the switch yet?

Perhaps the biggest reason is simply that universities are everywhere. Today, there are over 25,000 universities worldwide, with more than 264 million students enrolled globally (Higher Education, 2025). This makes change incredibly difficult. Beyond that, universities offer something that most online platforms cannot: accreditation. This is often a non-negotiable requirement in the job market. For example, many employers still require a formal degree when hiring, even if candidates have completed equivalent online courses. This institutional credibility remains one of the strongest advantages of universities.

It is not just about it being hard to change, as universities also provide something deeper. The word university comes from the Latin phrase universitas magistrorum et scholarium, meaning a “community of teachers and scholars” (Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911). This sense of community is hard to replicate online. Being part of a physical learning community—a real-life network of peers, mentors, and academics—is the foundation of any university.

There are advantages to physical communities, such as enhancing learning. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), learning is greatly enhanced through direct social engagement. For example, solving a difficult math problem becomes easier when a classmate or teacher can help in real time. Physical presence allows for spontaneous questions and immediate feedback, something online forums or pre-recorded videos often lack.

“Being part of a physical learning community—a real-life network of peers, mentors, and academics—is the foundation of any university.”

There are advantages to physical communities, such as enhancing learning. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), learning is greatly enhanced through direct social engagement. For example, solving a difficult math problem becomes easier when a classmate or teacher can help in real time. Physical presence allows for spontaneous questions and immediate feedback, something online forums or pre-recorded videos often lack.

Another advantage is that universities help satisfy our need to belong. Whether through participating in lectures, joining student-led activities, or engaging in campus events, these experiences play a key role in creating meaningful connections (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Subsequently, these experiences increase motivation to attend classes and follow through with assignments because feeling connected to others makes academic goals feel more meaningful and personally relevant (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Not only that, but they also contribute to the development of crucial soft skills like communication and teamwork. In contrast, online platforms often lack these dynamic and spontaneous opportunities for interaction, which can hinder engagement and motivation to learn (Richardson et al., 2017).

Universities also offer real-world learning beyond the classroom. Through student-led activities, internships, and exchange programs, students get hands-on experience. This aligns with Kolb’s experiential learning theory (1984), which emphasizes that learning is most effective when it involves a cycle of direct experience, reflection, and applying what was learned in new situations. For example, a psychology student interning at a counseling center can apply theoretical knowledge, reflect on their experiences, and refine their skills through feedback and practice. These opportunities for applied learning are difficult to replicate in online modules alone.

“Too often, students passively sit through hours of lectures, cram for exams, and forget most of the material within weeks.”

That said, universities are often criticized. Too often, students passively sit through hours of lectures, cram for exams, and forget most of the material within weeks (Kornell, 2009). Worse, many may spend years studying theory without ever applying it. A business student might study leadership extensively and write several academic papers about it but never lead a team. The student may know all the theory but lack the practical skills needed to manage people in a real-world setting. As the saying goes, “experience is the best teacher”, and too often there is a tangible gap between knowledge and application in university students.

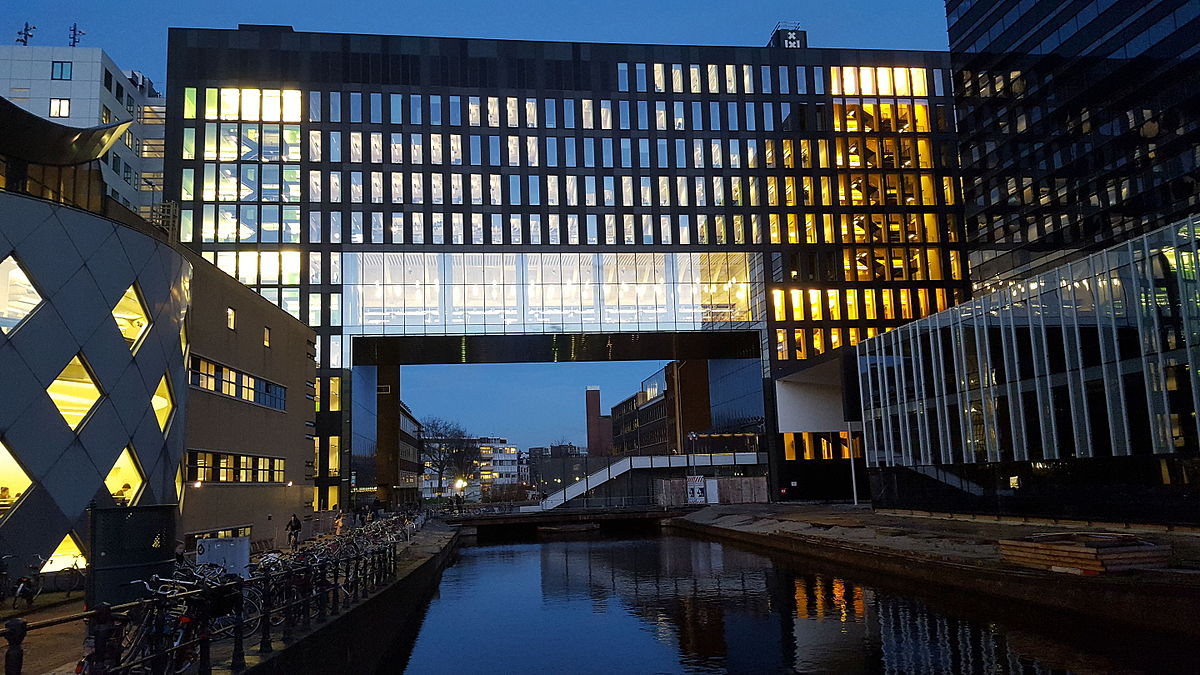

But some universities have begun to adapt, such as the University of Amsterdam (UvA). For instance, the Bachelor’s in Computational Social Science has completely replaced exams with project-based, active learning. Each semester, students work in small teams on real-world challenges often in collaboration with external partners such as NGOs or local governments. Students develop practical skills in data analysis, programming, and design—not by sitting through lectures, but by exploring real problems. As stated on the programme’s website, “it is not about reproducing knowledge but about integrating and applying knowledge, skills, and techniques” (Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2025). Students also have the freedom to choose their projects, aligning coursework with their personal interests and passions.

This marks a significant departure from the traditional university model, and with it, important benefits. Active learning methods have been shown to improve understanding and retention compared to passive forms of instruction (Tutal & Yazar, 2023). Furthermore, giving students more autonomy, such as choosing their own projects, can increase their engagement with their studies (Reeve, 2025). By building the curriculum around real-world projects and student autonomy, UvA puts students in the driver’s seat of their education, transforming them from passive recipients into active participants.

While online education may seem more efficient at first glance, it lacks the rich learning environment that universities offer. And though universities are far from perfect, some are already taking real steps to adapt. It is hard to predict exactly what the future of education holds, but one thing is for certain: universities are not going anywhere.

References

Encyclopædia Britannica. (1911). Universities. In Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed., Vol. XXVII, pp. 780–789). Cambridge University Press.

Higher education. (2025, June 23). UNESCO. https://www.unesco.org/en/higher-education

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

Kornell, N. (2009). Optimising learning using flashcards: Spacing is more effective than cramming. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23(9), 1297–1317. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1537

Reeve, J. (2025). Choosing to learn: The importance of student autonomy in higher education. Science Advances, advance publication. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado6759

Richardson, J. C., Maeda, Y., Lv, J., & Caskurlu, S. (2017). Social presence in relation to students’ satisfaction and learning in the online environment: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 402–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.001

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a Self‑Determination Theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Tutal, Ö., & Yazar, T. (2023). Active learning improves academic achievement and learning retention in K‑12 settings: A meta‑analysis. i‑manager’s Journal on School Educational Technology, 18(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.26634/jsch.18.3.19288

Universiteit van Amsterdam. (2025, May 28). Computational Social Science. University of Amsterdam. https://www.uva.nl/en/programmes/bachelors/computational-social-science/study-programme/study-programme.html#Encouraging-curious-learning

Platforms like Coursera, edX, and Khan Academy offer high-quality courses at a much lower cost than tuition-based education, sometimes even for free. They’re also highly flexible, since they are done online and at your own pace. Whether it is programming, marketing, psychology, or design, they can all be learned without ever stepping foot into a classroom. In terms of raw efficiency and accessibility, online platforms have the potential to outperform traditional education. So why haven’t we made the switch yet?

Perhaps the biggest reason is simply that universities are everywhere. Today, there are over 25,000 universities worldwide, with more than 264 million students enrolled globally (Higher Education, 2025). This makes change incredibly difficult. Beyond that, universities offer something that most online platforms cannot: accreditation. This is often a non-negotiable requirement in the job market. For example, many employers still require a formal degree when hiring, even if candidates have completed equivalent online courses. This institutional credibility remains one of the strongest advantages of universities.

It is not just about it being hard to change, as universities also provide something deeper. The word university comes from the Latin phrase universitas magistrorum et scholarium, meaning a “community of teachers and scholars” (Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911). This sense of community is hard to replicate online. Being part of a physical learning community—a real-life network of peers, mentors, and academics—is the foundation of any university.

There are advantages to physical communities, such as enhancing learning. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), learning is greatly enhanced through direct social engagement. For example, solving a difficult math problem becomes easier when a classmate or teacher can help in real time. Physical presence allows for spontaneous questions and immediate feedback, something online forums or pre-recorded videos often lack.

“Being part of a physical learning community—a real-life network of peers, mentors, and academics—is the foundation of any university.”

Another advantage is that universities help satisfy our need to belong. Whether through participating in lectures, joining student-led activities, or engaging in campus events, these experiences play a key role in creating meaningful connections (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Subsequently, these experiences increase motivation to attend classes and follow through with assignments because feeling connected to others makes academic goals feel more meaningful and personally relevant (Ryan & Deci, 2020). Not only that, but they also contribute to the development of crucial soft skills like communication and teamwork. In contrast, online platforms often lack these dynamic and spontaneous opportunities for interaction, which can hinder engagement and motivation to learn (Richardson et al., 2017).

Universities also offer real-world learning beyond the classroom. Through student-led activities, internships, and exchange programs, students get hands-on experience. This aligns with Kolb’s experiential learning theory (1984), which emphasizes that learning is most effective when it involves a cycle of direct experience, reflection, and applying what was learned in new situations. For example, a psychology student interning at a counseling center can apply theoretical knowledge, reflect on their experiences, and refine their skills through feedback and practice. These opportunities for applied learning are difficult to replicate in online modules alone.

“Too often, students passively sit through hours of lectures, cram for exams, and forget most of the material within weeks.”

That said, universities are often criticized. Too often, students passively sit through hours of lectures, cram for exams, and forget most of the material within weeks (Kornell, 2009). Worse, many may spend years studying theory without ever applying it. A business student might study leadership extensively and write several academic papers about it but never lead a team. The student may know all the theory but lack the practical skills needed to manage people in a real-world setting. As the saying goes, “experience is the best teacher”, and too often there is a tangible gap between knowledge and application in university students.

But some universities have begun to adapt, such as the University of Amsterdam (UvA). For instance, the Bachelor’s in Computational Social Science has completely replaced exams with project-based, active learning. Each semester, students work in small teams on real-world challenges often in collaboration with external partners such as NGOs or local governments. Students develop practical skills in data analysis, programming, and design—not by sitting through lectures, but by exploring real problems. As stated on the programme’s website, “it is not about reproducing knowledge but about integrating and applying knowledge, skills, and techniques” (Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2025). Students also have the freedom to choose their projects, aligning coursework with their personal interests and passions.

This marks a significant departure from the traditional university model, and with it, important benefits. Active learning methods have been shown to improve understanding and retention compared to passive forms of instruction (Tutal & Yazar, 2023). Furthermore, giving students more autonomy, such as choosing their own projects, can increase their engagement with their studies (Reeve, 2025). By building the curriculum around real-world projects and student autonomy, UvA puts students in the driver’s seat of their education, transforming them from passive recipients into active participants.

While online education may seem more efficient at first glance, it lacks the rich learning environment that universities offer. And though universities are far from perfect, some are already taking real steps to adapt. It is hard to predict exactly what the future of education holds, but one thing is for certain: universities are not going anywhere.