Art is often said to be the gateway to self expression. But what is truly being expressed? The artist’s identity – or the public’s thoughts and feelings about their own?

Art is often said to be the gateway to self expression. But what is truly being expressed? The artist’s identity – or the public’s thoughts and feelings about their own?

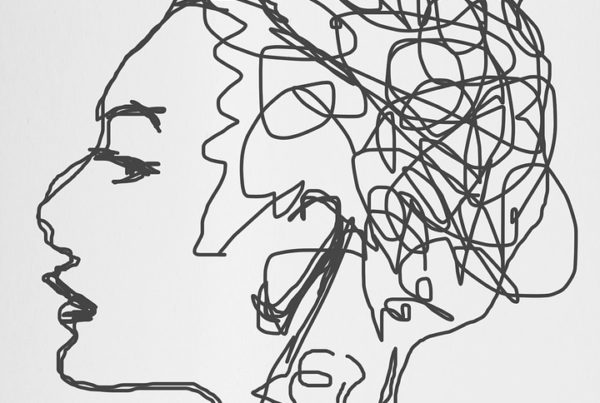

Photo by Malama Mushitu

Photo by Malama Mushitu

I grew up in quite the artsy family.

My mother wrote novels, my father played jazz music in a couple of bands, so naturally, I was also encouraged to incline myself to the arts. Periodically, my brothers and I were taken to art exhibitions by our mother to ‘’expand our worldview’’, as she would say. Most of these excursions have blurred in my memory, but one still stands out today: a Frida Kahlo exhibition I attended at the age of eight. For the first time, I saw a woman with a unibrow, a moustache, and an eccentrically colourful dress. How ugly, I thought. Why would anyone make themselves look that way?

I still don’t know exactly what Frida Kahlo’s intentions were behind those self-portraits, but I can attempt to decipher them today. They are three different perspectives on how the artist’s self relates to their art: as a lived experience, a social performance, and as something that may not exist at all – in order to ask whether art truly expresses the self, or whether it simply reflects the many ways we try (and fail) to define it.

One way to understand self-expression in art is through the ‘’experiential self’’.

The experiential self focuses on the subjective experience of the present moment, both physical and mental. For instance, as you are reading this article you might notice your eyelids getting heavy or your feet bouncing up and down the floor. You may be interested in what is being said to you, or instead, you may be slowly drifting away, thinking about your crush’s washboard abs.

The experiential self focuses on current sensations, wandering thoughts, and is also responsible for the phenomenon known as ‘’qualia’’ – the subjective qualities of conscious experiences. Qualia measures the ‘’what it’s like’’ dimension of experience, like the blueness of blue, the bitter taste of coffee or the softness of a cat’s fur. These subjective qualities cannot be described in words, in the same way that you cannot describe how green appears to a blind person. But art is a medium in which these subjective experiences can be communicated semi-accurately. A painting of a stormy sky may more closely encapsulate what it feels like to be angry than the simple statement ‘’I feel angry’’.

“By externalizing feelings or thoughts through artistic mediums, individuals can validate and process experiences in ways verbal therapy sometimes cannot.”

In art therapy, this understanding of the experiential self and qualia is central. By externalizing feelings or thoughts through artistic mediums, individuals can validate and process experiences in ways verbal therapy sometimes cannot. Art is thus an efficient way to portray the inner world and one’s uniqueness—every stroke, color, and shape gestures toward how the artist felt in the moment.

Yet, self-expression in art cannot be reduced to the experiential self. Art always carries a relational aspect, one that exists in the dialogue between artist and audience.

Art is not only about “self-expression” in the subjective sense—it also includes a performative side.

As Goffman (1956) theorized, all human interactions are, at their root, social performances. Artists do not create solely for the sake of their own self-expression; they also create with an audience in mind, often with the hope of recognition and profit. In this sense, art is less a solitary act and more of a social interaction.

The performative self encapsulates some of the darker aspects of human behavior: the need to impress, to be admired, to be seen. Not to be too cynical, but the archetype of the artist often includes a streak of self-absorption as well. According to Goffman, the performative self is responsible for impression management—the ways we shape our speech, behavior, or appearance depending on who is watching. In art, this translates into the importance of aesthetics and presentation. A painting deemed “ugly” is less likely to be valued than one judged “beautiful.” A dancer who fits the idealized image of grace and elegance is more likely to succeed than one who does not.

Art, then, also feeds the desire to be noticed and recognized. Praise and fame function are the currency of success in the art world, and entry into that success often depends on navigating the tightly knit networks of designers, directors, and curators. Even this article, in its own way, is performative. My reflections on self-expression in art may be irrelevant to most, but here I am, writing them down in the hope that someone, somewhere, might stumble across them out of curiosity.

But to claim that art is made to feed the ego of artists is quite reductive. The intent of the artist does not have to be a matter of the value of an art piece. Instead, art can be a mirror of the beholder’s own subjective experience.

The artist does not need to exist in their art in order for something to be expressed.

“While the ideas might feel unique, their expression inevitably relies on pre-existing cultural codes, symbols, and traditions.”

Barthes (1967) expressed the irrelevance of the artist as the ‘’death of the author’’. He claims that once a piece is published, the original intentions of the artist do not matter anymore, only the interpretation of the public does. For example ‘’Born in the USA’’ by Bruce Springsteen was originally written to protest against the mistreatment of Vietnam veterans in America. But, that doesn’t stop it from being used as a patriotic anthem during baseball games and republican political rallies. The meaning of the song escaped Springsteen’s intentions, living on independently through its reception.

Barthes also questioned the very idea of artistic originality. No thought exists in a purely mental vacuum—it must take shape in the material world, whether through paint, words, stone, or clay. While the ideas might feel unique, their expression inevitably relies on pre-existing cultural codes, symbols, and traditions. A painter may create a bold new canvas, but the brushstrokes, colors, and techniques all draw on a shared artistic language that belongs to no one. In this sense, art is less about a sovereign, isolated genius and more about weaving together fragments of what already exists.

If the author “dies,” then the beholder is “born.” Meaning is no longer anchored in the private imagination of the creator but emerges through interpretation. Each viewer, listener, or reader produces their own version of the work, and so an infinite number of meanings become possible. The responsibility of art, then, shifts away from the artist and toward the audience, who give the value of the work by making sense of it in their own way.

None of these types of self expressions are exclusive per se. Most art pieces contain elements of all three: they emerge from the artist’s lived experience, they perform within a social context, and once released, they belong as much to the audience as to their creator.

Was Frida Kahlo trying to convey pain in her self-portraits? Most definitely. Was she also showcasing her cultural identity? I guess so. Do her intentions matter in order for me to make an interpretation? Probably not. What ultimately remains of those paintings is the realization of my eight-year-old self that women can have moustaches just like men, and that my mother had a questionable taste in art exhibitions. Maybe that’s what self-expression really is: not the artist revealing themselves, but the audience discovering something about their own way of seeing.

References

- Barthes, R. (1967). The Death of the Author (S Heath, Trans.). Image, Music, Text, 142–148.https://sites.tufts.edu/english292b/files/2012/01/Barthes-The-Death-of-the-Author.pdf

- Madison, G. A., & Gendlin, E. T. (2014). Theory and practice of focusing-oriented psychotherapy : beyond the talking cure. In Jessica Kingsley Publishers eBooks. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB15934336

- Naegele, K. D., & Goffman, E. (1956). The presentation of self in everyday life. American Sociological Review, 21(5), 631. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089106

I grew up in quite the artsy family.

My mother wrote novels, my father played jazz music in a couple of bands, so naturally, I was also encouraged to incline myself to the arts. Periodically, my brothers and I were taken to art exhibitions by our mother to ‘’expand our worldview’’, as she would say. Most of these excursions have blurred in my memory, but one still stands out today: a Frida Kahlo exhibition I attended at the age of eight. For the first time, I saw a woman with a unibrow, a moustache, and an eccentrically colourful dress. How ugly, I thought. Why would anyone make themselves look that way?

I still don’t know exactly what Frida Kahlo’s intentions were behind those self-portraits, but I can attempt to decipher them today. They are three different perspectives on how the artist’s self relates to their art: as a lived experience, a social performance, and as something that may not exist at all – in order to ask whether art truly expresses the self, or whether it simply reflects the many ways we try (and fail) to define it.

One way to understand self-expression in art is through the ‘’experiential self’’.

The experiential self focuses on the subjective experience of the present moment, both physical and mental. For instance, as you are reading this article you might notice your eyelids getting heavy or your feet bouncing up and down the floor. You may be interested in what is being said to you, or instead, you may be slowly drifting away, thinking about your crush’s washboard abs.

The experiential self focuses on current sensations, wandering thoughts, and is also responsible for the phenomenon known as ‘’qualia’’ – the subjective qualities of conscious experiences. Qualia measures the ‘’what it’s like’’ dimension of experience, like the blueness of blue, the bitter taste of coffee or the softness of a cat’s fur. These subjective qualities cannot be described in words, in the same way that you cannot describe how green appears to a blind person. But art is a medium in which these subjective experiences can be communicated semi-accurately. A painting of a stormy sky may more closely encapsulate what it feels like to be angry than the simple statement ‘’I feel angry’’.

“By externalizing feelings or thoughts through artistic mediums, individuals can validate and process experiences in ways verbal therapy sometimes cannot.”

In art therapy, this understanding of the experiential self and qualia is central. By externalizing feelings or thoughts through artistic mediums, individuals can validate and process experiences in ways verbal therapy sometimes cannot. Art is thus an efficient way to portray the inner world and one’s uniqueness—every stroke, color, and shape gestures toward how the artist felt in the moment.

Yet, self-expression in art cannot be reduced to the experiential self. Art always carries a relational aspect, one that exists in the dialogue between artist and audience.

Art is not only about “self-expression” in the subjective sense—it also includes a performative side.

As Goffman (1956) theorized, all human interactions are, at their root, social performances. Artists do not create solely for the sake of their own self-expression; they also create with an audience in mind, often with the hope of recognition and profit. In this sense, art is less a solitary act and more of a social interaction.

The performative self encapsulates some of the darker aspects of human behavior: the need to impress, to be admired, to be seen. Not to be too cynical, but the archetype of the artist often includes a streak of self-absorption as well. According to Goffman, the performative self is responsible for impression management—the ways we shape our speech, behavior, or appearance depending on who is watching. In art, this translates into the importance of aesthetics and presentation. A painting deemed “ugly” is less likely to be valued than one judged “beautiful.” A dancer who fits the idealized image of grace and elegance is more likely to succeed than one who does not.

Art, then, also feeds the desire to be noticed and recognized. Praise and fame function are the currency of success in the art world, and entry into that success often depends on navigating the tightly knit networks of designers, directors, and curators. Even this article, in its own way, is performative. My reflections on self-expression in art may be irrelevant to most, but here I am, writing them down in the hope that someone, somewhere, might stumble across them out of curiosity.

But to claim that art is made to feed the ego of artists is quite reductive. The intent of the artist does not have to be a matter of the value of an art piece. Instead, art can be a mirror of the beholder’s own subjective experience.

The artist does not need to exist in their art in order for something to be expressed.

“While the ideas might feel unique, their expression inevitably relies on pre-existing cultural codes, symbols, and traditions.”

Barthes (1967) expressed the irrelevance of the artist as the ‘’death of the author’’. He claims that once a piece is published, the original intentions of the artist do not matter anymore, only the interpretation of the public does. For example ‘’Born in the USA’’ by Bruce Springsteen was originally written to protest against the mistreatment of Vietnam veterans in America. But, that doesn’t stop it from being used as a patriotic anthem during baseball games and republican political rallies. The meaning of the song escaped Springsteen’s intentions, living on independently through its reception.

Barthes also questioned the very idea of artistic originality. No thought exists in a purely mental vacuum—it must take shape in the material world, whether through paint, words, stone, or clay. While the ideas might feel unique, their expression inevitably relies on pre-existing cultural codes, symbols, and traditions. A painter may create a bold new canvas, but the brushstrokes, colors, and techniques all draw on a shared artistic language that belongs to no one. In this sense, art is less about a sovereign, isolated genius and more about weaving together fragments of what already exists.

If the author “dies,” then the beholder is “born.” Meaning is no longer anchored in the private imagination of the creator but emerges through interpretation. Each viewer, listener, or reader produces their own version of the work, and so an infinite number of meanings become possible. The responsibility of art, then, shifts away from the artist and toward the audience, who give the value of the work by making sense of it in their own way.

None of these types of self expressions are exclusive per se. Most art pieces contain elements of all three: they emerge from the artist’s lived experience, they perform within a social context, and once released, they belong as much to the audience as to their creator.

Was Frida Kahlo trying to convey pain in her self-portraits? Most definitely. Was she also showcasing her cultural identity? I guess so. Do her intentions matter in order for me to make an interpretation? Probably not. What ultimately remains of those paintings is the realization of my eight-year-old self that women can have moustaches just like men, and that my mother had a questionable taste in art exhibitions. Maybe that’s what self-expression really is: not the artist revealing themselves, but the audience discovering something about their own way of seeing.

References

- Barthes, R. (1967). The Death of the Author (S Heath, Trans.). Image, Music, Text, 142–148.https://sites.tufts.edu/english292b/files/2012/01/Barthes-The-Death-of-the-Author.pdf

- Madison, G. A., & Gendlin, E. T. (2014). Theory and practice of focusing-oriented psychotherapy : beyond the talking cure. In Jessica Kingsley Publishers eBooks. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB15934336

- Naegele, K. D., & Goffman, E. (1956). The presentation of self in everyday life. American Sociological Review, 21(5), 631. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089106