Music is an artform that everyone recognizes but would be hard-pressed to define. It is frequently described as a way of communication that is aesthetically pleasing and clearly distinguishable from noise (Godt, 2005). This definition becomes questionable when we consider the diversity of music across the world – some pieces sound wildly chaotic and seemingly devoid of any musical elements. Why would anyone listen to that? This article explores the world of conventionally unpleasant and chaotic music and how it can still provide the listener with a meaningful experience.

Listen along to this article on Spotify.

Music is an artform that everyone recognizes but would be hard-pressed to define. It is frequently described as a way of communication that is aesthetically pleasing and clearly distinguishable from noise (Godt, 2005). This definition becomes questionable when we consider the diversity of music across the world – some pieces sound wildly chaotic and seemingly devoid of any musical elements. Why would anyone listen to that? This article explores the world of conventionally unpleasant and chaotic music and how it can still provide the listener with a meaningful experience.

Listen along to this article on Spotify.

Photo by Yulia Gapeenko

Photo by Yulia Gapeenko

From a technical perspective, music consists of three elements: harmony, melody and rhythm (Guernsay, 1929). Many musical pieces and genres – from rock and funk to k-pop and jazz – include these elements. In other words, most people enjoy pleasant-sounding music with periodic rhythms that one can enjoy and dance to. Out of curiosity, one might ponder though: How many elements can we take away before music ceases to be music?

Starting with harmony, on the one hand we have pleasantly harmonious compositions like Shostakovich’s Fugue No. 7 in A major. On the other hand, we have dissonant compositions like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and Mozart’s String Quartet No. 19. While some studies imply cultural variation in the perceived pleasantness of dissonant sounds (McDermott et al., 2016), they are generally described as sounding ‘crunchy’ and ‘unstable’ (Johnson-Laird et al., 2012, soundclip). However, for the very reason that dissonance sounds unpleasant, it creates a tension and instability that seeks to be resolved in consonance. Musicians across genres agree that the interplay or ‘push and pull’ between harmony and dissonance gives music its movement and emotional drive (Parncutt & Hair, 2011). This concept should be familiar to psychology students who are acquainted with the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) – similar to how soundwaves which clash together make us crave resolution and harmony, misaligned attitudes and behaviours can drive us to change them in search for alignment.

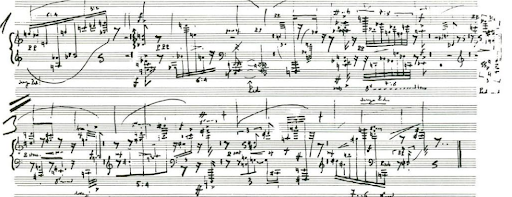

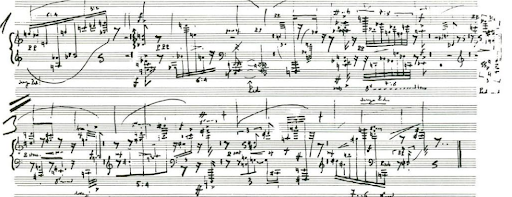

What happens if we also play around with rhythm? The same question appeared to those musicians of the mid-20th century who we now remember as the pioneers of experimental music (Cage, 1961). The premise of early experimentalists was to express their creativity to the fullest and push music to its conceivable boundaries (Lockwood & Nyman, 1975). Take a look at the image below for a piece of John Cage’s Notations (1969), in which time signatures and other rules of music notation are freely abandoned.

Note. Excerpt from Notations (Cage, 1969).

“How many elements can we take away before music ceases to be music?”

Cage occasionally even let a throw of dice decide on the next musical phrase (Miksa, 2023). Both are examples of the indeterminacy that experimentalists were after: through randomness in the composition or through fully surrendering the music to the performer’s interpretation, experimentalists created utterly unpredictable and unique pieces. Arguably, the most radical of Cage’s pieces is 4”33 (recommended listen). In 4”33’s complete abandonment of melody as well as harmony and rhythm, it is a statement that music can be anything, even the complete silence or ambient noise produced by a crowd of people.

Following early experimentalism, other music genres similarly called for a revolution of the status quo, like industrial music which highlighted the struggles of a dehumanised society after the great industrial movements (Hanley, 2011). Especially British industrialism painted a dystopian picture of society, reflected in harsh and abrasive music (Street Sects’ The Drifter). Part of the industrial genre developed into noise music, and what began as ambience music gradually turned into mind-numbing chaos like Borbetomagus’ The Challenger Deep. Pulse Demon by Japanese artist Merzbow is considered one of the most influential albums of the genre (Hegarty, 2001). Would you dare to put this record on that a first-time listener might describe as “putting your ear towards an underwater jet in a jacuzzi” (Pad Chenning, 2020)? If so, what do you make of this chaotic and unpredictable stream of layered, unpleasant sounds?

People with a similar curiosity questioned online forums, and anecdotal evidence suggests that noise music is both about the creative process of making noise (boywithapplesauce, 2020) and the listening experience. Some users enjoy the intense auditory stimulation and unexpectedness (capnrondo, 2020). They report that harsh noise music can force you to listen and shut out everything else that might have been going on in your mind (Pad Chenning, 2020). As such, noise music can be considered as a “musical palate cleanser” because it invites the listener to perk up their ears and focus on the nuances to be found in the mess of layered sound (qmsocialclub, 2020).

Let us try to put that anecdotal evidence into the context of brain studies. It is repeatedly shown that music affects the autonomic nervous system by initiating reflexive brainstem responses, i.e. changing heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension (Chanda & Levitin, 2013). In other words, music can increase or decrease arousal. These effects arise because our brain does not interpret music differently from any other sounds that signal danger (harsh, alarming sounds) or safety (calm, relaxing sounds). It is indeed found that calm music decreases arousal, stress and pain perception (Dileo & Bradt, 2007; Knight & Rickard, 2001). However, brain studies also reflect the interindividual differences found in anecdotal evidence. Furnham and Strbac (2002) investigated if different sound conditions would affect introverts’ versus extraverts’ performance on cognitive tasks differently. They indeed found that on a reading comprehension task, extraverts performed better than introverts during exposure to music and noise while they performed comparably during silence. This is also in line with the hypothesis that introverts and extraverts might have different optimal arousal levels (Furnham & Strbac, 2002). Gerra et al. (1998) tested the effect of relaxing versus fast-paced techno music. As expected, they found that techno music increased arousal and stress hormone levels (cortisol and norepinephrine), but this was especially true for people who had certain personality profiles, such as an increased tendency for novelty-seeking and a decreased tendency to avoid harm. While these results are fascinating and imply numerous hypotheses, the research on the effect of music still produces many inconsistent results. This is probably because it is difficult to define music in objective terms, which would allow for better manipulation checks and replication (Wang & Wang, 2001; Chanda & Levitin, 2013).

“While these communities are originally composed of people, Woods (2022) suggests that they should also encompass how individuals can acquire musical skills through experimenting with tools and material objects of all kinds.”

Although the effects of listening to noise remain difficult to disentangle, there is something to be said about the effect of producing noise music yourself. Woods (2022) conducted a qualitative study on the creative process and observed that the noise musician often takes on an independent autodidactic approach in which they learn to use tools for creating noise – or ‘allowing the tools to teach them’ about their different uses in an exploratory way. For example, noise musicians might explore the different sounds that a chair or a pair of clips can make to create a layered record (Woods, 2022). This observation expands the theory of situation learning – a theory which states that learning happens in a community of practice where the learner first observes the existent cultural practices before slowly contributing themselves (Anderson et al., 1996). While these communities are originally composed of people, Woods (2022) suggests that they should also encompass how individuals can acquire musical skills through experimenting with tools and material objects of all kinds. The use of such instrumental improvisation cannot only help people expand their musical capacity, but research on music therapy also suggests that it can help with pain management (Bradt et al., 2024), motor control (Dan et al., 2025) and mental health issues (Vobig, 2025).

Elements of music help us define it in technical terms, but different music examples show us that we do not need to adhere to the conventional rules in order to create meaningful experiences – the interplay of harmony and dissonance can drive us emotionally while the play with rhythm and melody can serve as a call for revolution. What is more, even the consumption and creation of chaotic noise can be a rewarding stimulation – it all depends on how much chaos you dare to invite into your experience of music.

Intrigued by this article and in search for more chaotic music? Check out this playlist.

References

- Anderson, J. R., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (1996). Situated Learning and education. Educational Researcher, 25(4), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×025004005

- boywithapplesauce (2020). I can best enjoy noise and sound art in a performative

- context. It can be a fascinating, even exhilarating experience, [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Bradt, J., Leader, A., Worster, B., Myers‐Coffman, K., Bryl, K., Biondo, J., Schneible, B., Cottone, C., Selvan, P., & Zhang, F. (2024). Music Therapy for pain management for people with advanced Cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology, 33(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.70005

- Cage, J. (1961). Experimental music. Silence: Lectures and writings, 7, 12.

- Cage, J. (1969). Notations. Something Else Press, New York. https://monoskop.org/images/9/92/Cage_John_Notations.pdf

- capnrondo (2020). I find the right noise very satisfying on the ears. I liken it to how some people experience ASMR from soft noises… grating, harsh noises trigger some kind of pleasant response in my brain. [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Chanda, M. L., & Levitin, D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends in cognitive sciences, 17(4), 179-193. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/articles/br86b770c

- Dan, Y., Xiong, Y., Xu, D., Wang, Y., Yin, M., Sun, P., … & Li, L. (2025). Potential common targets of music therapy intervention in neuropsychiatric disorders: the prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-amygdala circuit (a review). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 19, 1471433.

- Daniels, A., Mann, A., & Edmunds, J. (1967). The Study of Counterpoint. From Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum. Notes, 23(4), 744. https://doi.org/10.2307/894303

- Dileo, C. and Bradt, J. (2007) Music therapy: applications to stress management. In Principles and Practice of Stress Management (Lehrer, P.M. et al., eds), pp. 519–544, Guilford Press

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. In Stanford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503620766

- Gradus ad parnassum. (2024, October 6). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gradus_ad_Parnassum

- Godt, I. (2005). Music: A practical definition. The Musical Times, 146(1890), 83. https://doi.org/10.2307/30044071

- Goltz, F., & Sadakata, M. (2021). Do you listen to music while studying? A portrait of how people use music to optimize their cognitive performance. Acta Psychologica, 220, 103417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103417

- Hanley, J. J. (2011). Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975–1996. https://ir.stonybrook.edu/xmlui/handle/11401/71615

- Hegarty, P. (2001). Noise threshold: Merzbow and the end of natural sound. Organised Sound, 6(3), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355771801003053

- Johnson-Laird, P. N., Kang, O. E., & Leong, Y. C. (2012). On musical dissonance. Music Perception an Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2012.30.1.19

- Knight, W. E. J., & Rickard, N. S. (2001). Relaxing music prevents stress induced increases in subjective anxiety, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in healthy males and females. J. Music Ther. 38, 254–272

- Leardi, S., Pietroletti, R., Angeloni, G., Necozione, S., Ranalletta, G., & Del Gusto, B. (2007). Randomized clinical trial examining the effect of music therapy in stress response to day surgery. British Journal of Surgery, 94(8), 943–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5914

- Lockwood, L., & Nyman, M. (1975). Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. Notes, 32(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.2307/896320

- McDermott, J. H., Schultz, A. F., Undurraga, E. A., & Godoy, R. A. (2016). Indifference to dissonance in native Amazonians reveals cultural variation in music perception. Nature, 535(7613), 547–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18635

- Miksa, D. (2023). Probability-based Approaches to Modern Music Composition and Production (Doctoral dissertation, University Honors College, Middle Tennessee State University).

- Pad Chenning. (2020, January 23). The Brutal World of Noise Music [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MM5RSYayLCg

- Parncutt, R., & Hair, G. (2011). Consonance and dissonance in music theory and psychology: Disentangling dissonant dichotomies. Journal of interdisciplinary music studies, 5(2).

- Ridgeway, D., & Hare, R. D. (1981). Sensation seeking and psychophysiological responses to auditory stimulation. Psychophysiology, 18(6), 613–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1981.tb01833.x

- qmsocialclub (2020). Sometimes I get bored of everything. Music I’ve loved for 15 years, new music that I should love, things that are right up my alley. That’s when I really enjoy going into noise for a bit to cleanse my pallet. [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Vobig, B. (2025). A Computational approach to interaction type analysis of music therapy improvisations. Music & Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043251329233

- Wang, W., & Wang, Y. (2001). Sensation seeking correlates of passive auditory P3 to a single stimulus. Neuropsychologia, 39(11), 1188–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00051-3

- Woods, P. J. (2022). Learning to make noise: toward a process model of artistic practice within experimental music scenes. Mind Culture and Activity, 29(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2022.2098337

- yganko (2025). music notes background [Illustration]. Vecteezy. https://www.vecteezy.com/photo/24295098-music-notes-background-illustration-ai-generative?autodl_token=b5a914470405cffedde4be980fd84de4cef7b4451f64f26e7137bb31d3b87877c5431c0bc984abb76fee70fcdd655fda754c4ed5ff9fcdb4769f7ea4924b6f7e

From a technical perspective, music consists of three elements: harmony, melody and rhythm (Guernsay, 1929). Many musical pieces and genres – from rock and funk to k-pop and jazz – include these elements. In other words, most people enjoy pleasant-sounding music with periodic rhythms that one can enjoy and dance to. Out of curiosity, one might ponder though: How many elements can we take away before music ceases to be music?

Starting with harmony, on the one hand we have pleasantly harmonious compositions like Shostakovich’s Fugue No. 7 in A major. On the other hand, we have dissonant compositions like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and Mozart’s String Quartet No. 19. While some studies imply cultural variation in the perceived pleasantness of dissonant sounds (McDermott et al., 2016), they are generally described as sounding ‘crunchy’ and ‘unstable’ (Johnson-Laird et al., 2012, soundclip). However, for the very reason that dissonance sounds unpleasant, it creates a tension and instability that seeks to be resolved in consonance. Musicians across genres agree that the interplay or ‘push and pull’ between harmony and dissonance gives music its movement and emotional drive (Parncutt & Hair, 2011). This concept should be familiar to psychology students who are acquainted with the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957) – similar to how soundwaves which clash together make us crave resolution and harmony, misaligned attitudes and behaviours can drive us to change them in search for alignment.

What happens if we also play around with rhythm? The same question appeared to those musicians of the mid-20th century who we now remember as the pioneers of experimental music (Cage, 1961). The premise of early experimentalists was to express their creativity to the fullest and push music to its conceivable boundaries (Lockwood & Nyman, 1975). Take a look at the image below for a piece of John Cage’s Notations (1969), in which time signatures and other rules of music notation are freely abandoned.

Note. Excerpt from Notations (Cage, 1969).

“How many elements can we take away before music ceases to be music?”

Cage occasionally even let a throw of dice decide on the next musical phrase (Miksa, 2023). Both are examples of the indeterminacy that experimentalists were after: through randomness in the composition or through fully surrendering the music to the performer’s interpretation, experimentalists created utterly unpredictable and unique pieces. Arguably, the most radical of Cage’s pieces is 4”33 (recommended listen). In 4”33’s complete abandonment of melody as well as harmony and rhythm, it is a statement that music can be anything, even the complete silence or ambient noise produced by a crowd of people.

Following early experimentalism, other music genres similarly called for a revolution of the status quo, like industrial music which highlighted the struggles of a dehumanised society after the great industrial movements (Hanley, 2011). Especially British industrialism painted a dystopian picture of society, reflected in harsh and abrasive music (Street Sects’ The Drifter). Part of the industrial genre developed into noise music, and what began as ambience music gradually turned into mind-numbing chaos like Borbetomagus’ The Challenger Deep. Pulse Demon by Japanese artist Merzbow is considered one of the most influential albums of the genre (Hegarty, 2001). Would you dare to put this record on that a first-time listener might describe as “putting your ear towards an underwater jet in a jacuzzi” (Pad Chenning, 2020)? If so, what do you make of this chaotic and unpredictable stream of layered, unpleasant sounds?

People with a similar curiosity questioned online forums, and anecdotal evidence suggests that noise music is both about the creative process of making noise (boywithapplesauce, 2020) and the listening experience. Some users enjoy the intense auditory stimulation and unexpectedness (capnrondo, 2020). They report that harsh noise music can force you to listen and shut out everything else that might have been going on in your mind (Pad Chenning, 2020). As such, noise music can be considered as a “musical palate cleanser” because it invites the listener to perk up their ears and focus on the nuances to be found in the mess of layered sound (qmsocialclub, 2020).

Let us try to put that anecdotal evidence into the context of brain studies. It is repeatedly shown that music affects the autonomic nervous system by initiating reflexive brainstem responses, i.e. changing heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension (Chanda & Levitin, 2013). In other words, music can increase or decrease arousal. These effects arise because our brain does not interpret music differently from any other sounds that signal danger (harsh, alarming sounds) or safety (calm, relaxing sounds). It is indeed found that calm music decreases arousal, stress and pain perception (Dileo & Bradt, 2007; Knight & Rickard, 2001). However, brain studies also reflect the interindividual differences found in anecdotal evidence. Furnham and Strbac (2002) investigated if different sound conditions would affect introverts’ versus extraverts’ performance on cognitive tasks differently. They indeed found that on a reading comprehension task, extraverts performed better than introverts during exposure to music and noise while they performed comparably during silence. This is also in line with the hypothesis that introverts and extraverts might have different optimal arousal levels (Furnham & Strbac, 2002). Gerra et al. (1998) tested the effect of relaxing versus fast-paced techno music. As expected, they found that techno music increased arousal and stress hormone levels (cortisol and norepinephrine), but this was especially true for people who had certain personality profiles, such as an increased tendency for novelty-seeking and a decreased tendency to avoid harm. While these results are fascinating and imply numerous hypotheses, the research on the effect of music still produces many inconsistent results. This is probably because it is difficult to define music in objective terms, which would allow for better manipulation checks and replication (Wang & Wang, 2001; Chanda & Levitin, 2013).

“While these communities are originally composed of people, Woods (2022) suggests that they should also encompass how individuals can acquire musical skills through experimenting with tools and material objects of all kinds.”

Although the effects of listening to noise remain difficult to disentangle, there is something to be said about the effect of producing noise music yourself. Woods (2022) conducted a qualitative study on the creative process and observed that the noise musician often takes on an independent autodidactic approach in which they learn to use tools for creating noise – or ‘allowing the tools to teach them’ about their different uses in an exploratory way. For example, noise musicians might explore the different sounds that a chair or a pair of clips can make to create a layered record (Woods, 2022). This observation expands the theory of situation learning – a theory which states that learning happens in a community of practice where the learner first observes the existent cultural practices before slowly contributing themselves (Anderson et al., 1996). While these communities are originally composed of people, Woods (2022) suggests that they should also encompass how individuals can acquire musical skills through experimenting with tools and material objects of all kinds. The use of such instrumental improvisation cannot only help people expand their musical capacity, but research on music therapy also suggests that it can help with pain management (Bradt et al., 2024), motor control (Dan et al., 2025) and mental health issues (Vobig, 2025).

Elements of music help us define it in technical terms, but different music examples show us that we do not need to adhere to the conventional rules in order to create meaningful experiences – the interplay of harmony and dissonance can drive us emotionally while the play with rhythm and melody can serve as a call for revolution. What is more, even the consumption and creation of chaotic noise can be a rewarding stimulation – it all depends on how much chaos you dare to invite into your experience of music.

Intrigued by this article and in search for more chaotic music? Check out this playlist.

References

- Anderson, J. R., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (1996). Situated Learning and education. Educational Researcher, 25(4), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×025004005

- boywithapplesauce (2020). I can best enjoy noise and sound art in a performative

- context. It can be a fascinating, even exhilarating experience, [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Bradt, J., Leader, A., Worster, B., Myers‐Coffman, K., Bryl, K., Biondo, J., Schneible, B., Cottone, C., Selvan, P., & Zhang, F. (2024). Music Therapy for pain management for people with advanced Cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology, 33(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.70005

- Cage, J. (1961). Experimental music. Silence: Lectures and writings, 7, 12.

- Cage, J. (1969). Notations. Something Else Press, New York. https://monoskop.org/images/9/92/Cage_John_Notations.pdf

- capnrondo (2020). I find the right noise very satisfying on the ears. I liken it to how some people experience ASMR from soft noises… grating, harsh noises trigger some kind of pleasant response in my brain. [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Chanda, M. L., & Levitin, D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends in cognitive sciences, 17(4), 179-193. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/articles/br86b770c

- Dan, Y., Xiong, Y., Xu, D., Wang, Y., Yin, M., Sun, P., … & Li, L. (2025). Potential common targets of music therapy intervention in neuropsychiatric disorders: the prefrontal cortex-hippocampus-amygdala circuit (a review). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 19, 1471433.

- Daniels, A., Mann, A., & Edmunds, J. (1967). The Study of Counterpoint. From Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum. Notes, 23(4), 744. https://doi.org/10.2307/894303

- Dileo, C. and Bradt, J. (2007) Music therapy: applications to stress management. In Principles and Practice of Stress Management (Lehrer, P.M. et al., eds), pp. 519–544, Guilford Press

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. In Stanford University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503620766

- Gradus ad parnassum. (2024, October 6). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gradus_ad_Parnassum

- Godt, I. (2005). Music: A practical definition. The Musical Times, 146(1890), 83. https://doi.org/10.2307/30044071

- Goltz, F., & Sadakata, M. (2021). Do you listen to music while studying? A portrait of how people use music to optimize their cognitive performance. Acta Psychologica, 220, 103417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2021.103417

- Hanley, J. J. (2011). Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975–1996. https://ir.stonybrook.edu/xmlui/handle/11401/71615

- Hegarty, P. (2001). Noise threshold: Merzbow and the end of natural sound. Organised Sound, 6(3), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355771801003053

- Johnson-Laird, P. N., Kang, O. E., & Leong, Y. C. (2012). On musical dissonance. Music Perception an Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2012.30.1.19

- Knight, W. E. J., & Rickard, N. S. (2001). Relaxing music prevents stress induced increases in subjective anxiety, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in healthy males and females. J. Music Ther. 38, 254–272

- Leardi, S., Pietroletti, R., Angeloni, G., Necozione, S., Ranalletta, G., & Del Gusto, B. (2007). Randomized clinical trial examining the effect of music therapy in stress response to day surgery. British Journal of Surgery, 94(8), 943–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5914

- Lockwood, L., & Nyman, M. (1975). Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. Notes, 32(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.2307/896320

- McDermott, J. H., Schultz, A. F., Undurraga, E. A., & Godoy, R. A. (2016). Indifference to dissonance in native Amazonians reveals cultural variation in music perception. Nature, 535(7613), 547–550. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18635

- Miksa, D. (2023). Probability-based Approaches to Modern Music Composition and Production (Doctoral dissertation, University Honors College, Middle Tennessee State University).

- Pad Chenning. (2020, January 23). The Brutal World of Noise Music [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MM5RSYayLCg

- Parncutt, R., & Hair, G. (2011). Consonance and dissonance in music theory and psychology: Disentangling dissonant dichotomies. Journal of interdisciplinary music studies, 5(2).

- Ridgeway, D., & Hare, R. D. (1981). Sensation seeking and psychophysiological responses to auditory stimulation. Psychophysiology, 18(6), 613–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1981.tb01833.x

- qmsocialclub (2020). Sometimes I get bored of everything. Music I’ve loved for 15 years, new music that I should love, things that are right up my alley. That’s when I really enjoy going into noise for a bit to cleanse my pallet. [Comment on the online forum post Serious question: Does anyone actually enjoy noise music?]. Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/LetsTalkMusic/comments/j6u3tg/serious_question_does_anyone_actually_enjoy_noise/

- Vobig, B. (2025). A Computational approach to interaction type analysis of music therapy improvisations. Music & Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043251329233

- Wang, W., & Wang, Y. (2001). Sensation seeking correlates of passive auditory P3 to a single stimulus. Neuropsychologia, 39(11), 1188–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0028-3932(01)00051-3

- Woods, P. J. (2022). Learning to make noise: toward a process model of artistic practice within experimental music scenes. Mind Culture and Activity, 29(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2022.2098337

- yganko (2025). music notes background [Illustration]. Vecteezy. https://www.vecteezy.com/photo/24295098-music-notes-background-illustration-ai-generative?autodl_token=b5a914470405cffedde4be980fd84de4cef7b4451f64f26e7137bb31d3b87877c5431c0bc984abb76fee70fcdd655fda754c4ed5ff9fcdb4769f7ea4924b6f7e