Anomalies are usually triggering for us. Imagine your doctor telling you that there’s an anomaly in your blood test. You would be alarmed, would try to understand the situation, and would look for solutions that alleviate the problem.

Currently, a triggering anomaly that lives in my head rent-free is the climate patterns that we observe. The science is clear that the current average global temperatures and the frequency of the extreme weather events are an anomaly, but why are we not displaying the same sense of urgency as other anomalies do? Is it not triggering enough?

I do not think so. This idea, that we might have an inhabitable planet in the (near) future, is so often iterated in our everyday discourse. We see it in movies, in the news, it pops up in daily conversations with friends, we read about it, write about it… we experience this in all domains of life.

We, as humans, like to look into the future, see a future, and dream of a better future. This desire for imagination and long-term planning is one of the most distinguishing qualities of humans that sets us apart from other species. So, no, this threat should be affecting us deeply, at least on an unconscious level. Then why are we not immediately acting to solve it?

I feel like most of us – at least in our ‘WEIRD’ bubble – are paralyzed by the immensity of the problem. The climate crisis is very intricately woven into the fabric of society: the economics of it, the social aspects, the politics, the injustice, everything. You would think that untangling it, and solving it just by itself, would require a magic wand with unlimited capabilities.

Take a deep breath… Maybe this is okay. Maybe the storm brought about by the winds of climate change is good. They might even pose an opportunity: “climate change may be a perfect moral storm […] its complexity may turn out to be perfectly convenient for us” (Gardiner, 2006). It is an opportunity to solve the rotten part of our society.

We need a massive, I mean massive, shift in our society. It is, right now, normal to blame the current capitalist system, with its massive emphasis on profit and growth, for the sorry state we are in today. Addressing climate change requires rethinking capitalism, to prioritise the well-being of both people and the planet.

I, however, find it daunting to create monsters that seem too big to defeat. And when we say ‘capitalism’ or ‘the system’, aren’t we doing just this? Maybe, it is easier to take down a structure by slowly damaging its pillars. And I have the perfect starting point in mind.

One of the pillars of the current capitalist framework is meritocracy, which is essentially based on free will. A meritocracy “is a society in which influence (of some sort) is possessed on the basis of merit (whatever that means)” (Mulligan, 2023), with a proposed framework for ‘equal opportunities for all’ given that one has free will to work hard. So, when we are rewarded in this system, we feel like we have earned it since we ‘worked very hard for it’, or we ‘have talent’, or we ‘are smart’.

But are these rewards that are so unequally distributed in society really justified? Throughout the last century, our knowledge of human behaviour has increased with psychological science, but this actually has not yet reflected well enough on our beliefs in free will: our science does show that we are inexorably affected by our genes, and the political, economic and socio-cultural climate we get thrown into when we are born, nonetheless we still have a strong – and considering the science, unjustified – belief that we are ‘free’ to make decisions independently of external influences.

Many aspects of our societal system are based on this notion of free will, including meritocracy. And I believe that we need to replace the aspects of our system that are heavily based on free will if we want to undermine capitalism. So what would a society with less belief in free will, and, therefore, meritocracy, mean for the climate crisis?

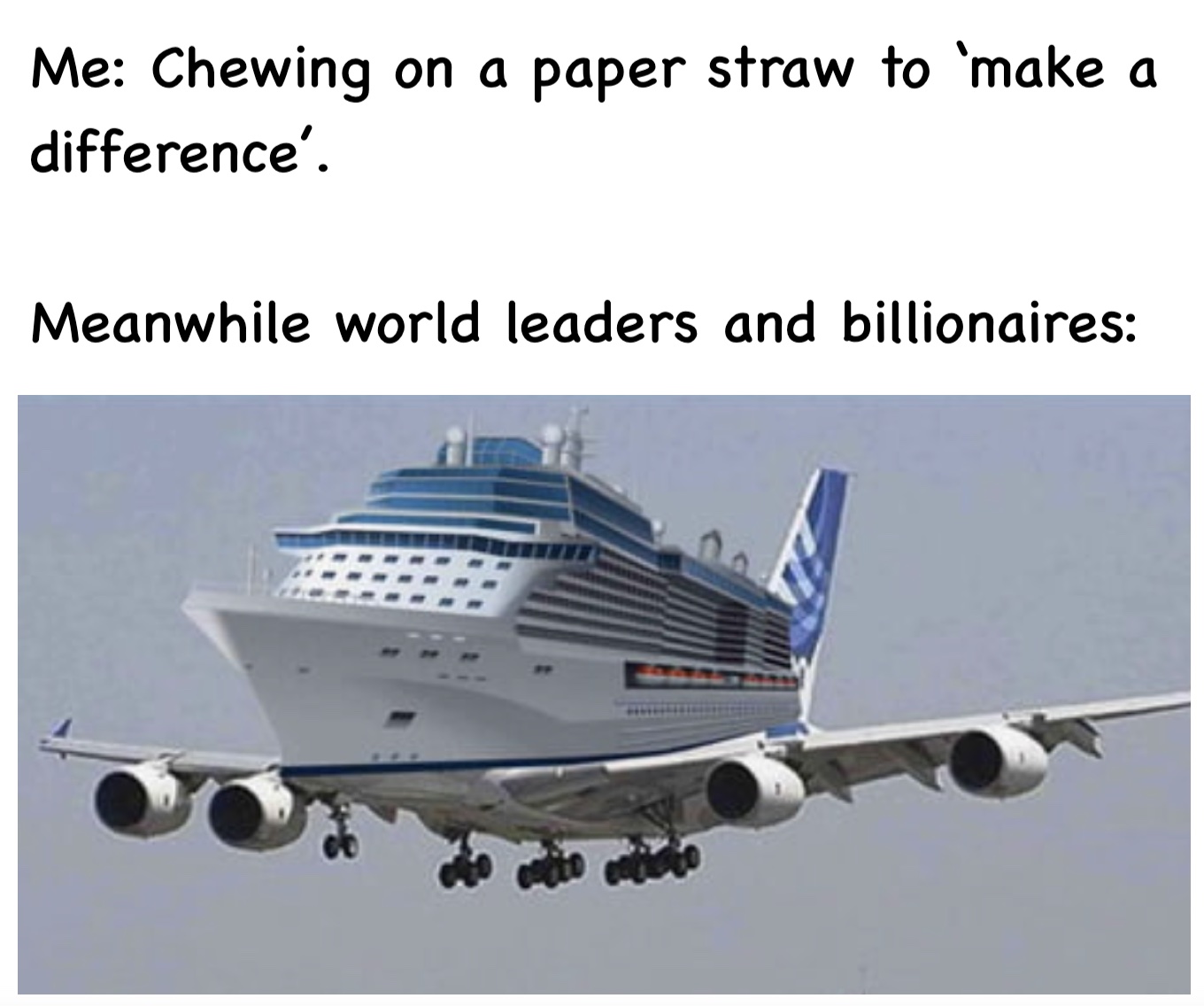

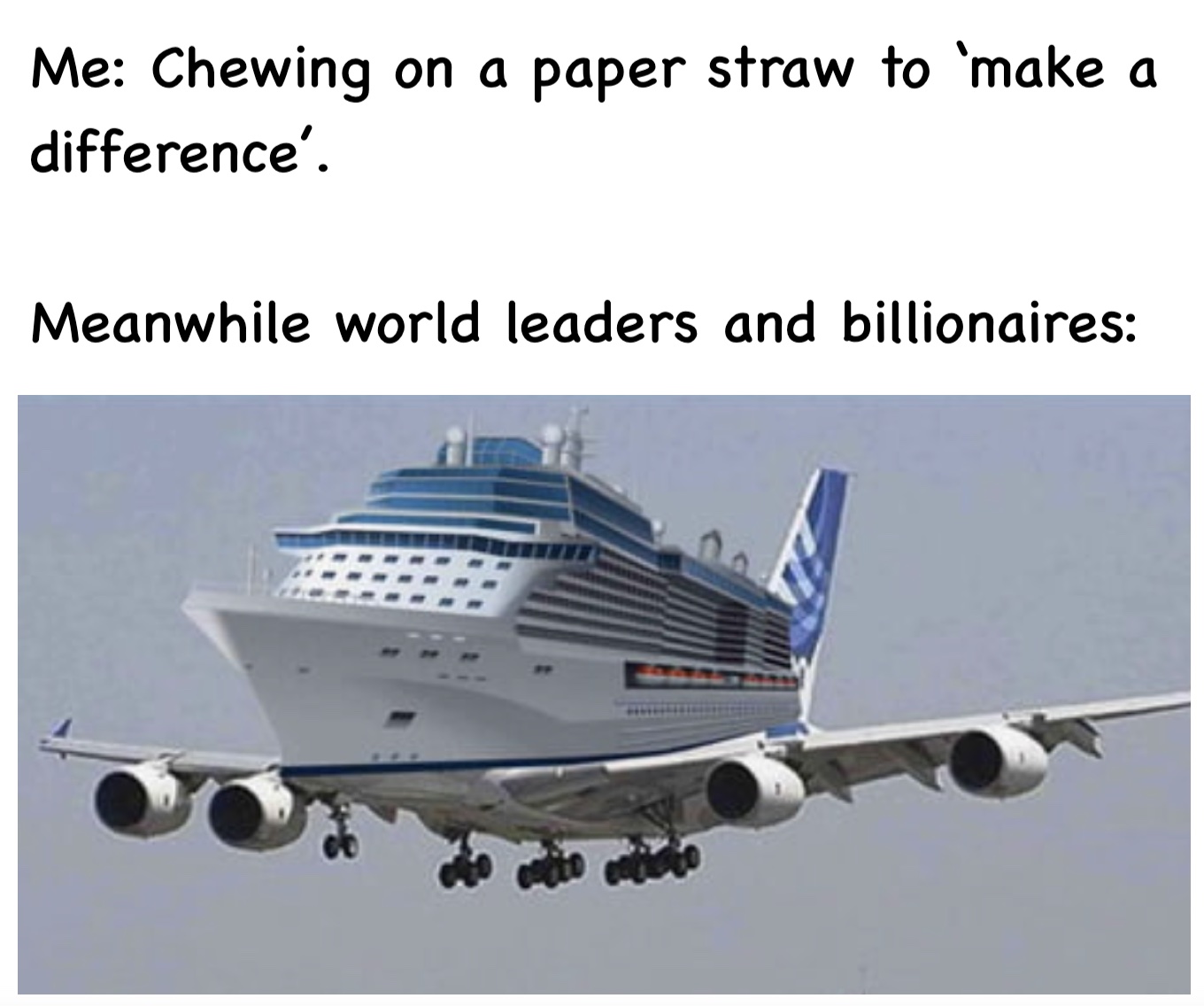

Well, most of the achievements that we are proud of, and the consumerist lifestyle that we think that we are entitled to, is actually just mere chance: we were born in some part of the world where people gained riches through the exploitation of the others, and not in another where people and their society have been exploited for hundreds of years. Then, logically following from this, billionaires, or even millionaires for that matter, that wreak havoc upon the planet – “Globally, the top 10% of emitters were responsible for almost half of global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021” (Cozzi et al., 2023) – should not exist, they are simply a policy failure and an ugly reminder of brutal inequalities.

On a more system-level, our desire for never-ending economic growth needs to change, and less belief in free will can actually help this transition. This is because the current system relies upon its individuals to have a productivity-maximising mentality, which comes as a package deal with meritocracy and free will, since one usually needs to choose to ‘grind’ in order to become successful. In return, thanks to its well-behaved hard-working parts – that’s us –, the economy keeps growing with an undying appetite, which in turn exacerbates the climate crisis.

The funny thing is, most of humanity is not really happy with the burden of this belief in free will either. This is because there are actually two sides to this: yes, it does suggest that you are responsible for your own happiness, but it also automatically entails that if you have not achieved ‘your dreams’ – which, by the way, are a product of our times in and of themselves anyways – the fault is on you. Which is completely ridiculous considering all the factors that you are not in control of. This whole thing is a great way to shift the attention from the structural inequalities and injustices to the individual, which further perpetuates these structural inequalities and injustices.

If we ease this burden, then we ease the pressure for ourselves to become ‘better’ agents of the system. Instead of striving for individual success, we can give more importance to spending time with loved ones and feelings of community. Instead of promoting ambition, greed, and consumerism, we can promote kindness, caring, and enjoyment of life. This new way of existence will in turn alleviate the climate crisis.

Finally, rethinking free will also allows us to consider our place in the world. Most religions that have been massively important in shaping our thinking throughout history tend to put humans as the centre of the universe, indirectly giving us the right for environmental destruction and mass extinction simply because everything was created for us. If individuals are not ultimately responsible for their choices and actions due to a lack of free will, it challenges the traditional notions of deserving reward or punishment in an afterlife. Hence, getting rid of our belief in complete free will would also entail killing God and his heavens, but, well, who cares about it if we hella hot down here.

The idea of the necessity of a system change to tackle the climate crisis is not new. However, how we need to rethink free will, considering its massive importance for this system to function, is never addressed. Maybe the climate anomalies are just symptoms of a disease in our system of thinking and beliefs. And it is always good to have the right diagnosis.

References

– Cozzi, L., Chen, O., & Kim, H. (2023, February 22). The world’s top 1% of emitters produce over 1000 times more CO2 than the bottom 1% – Analysis. International Energy Agency: IEA. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-world-s-top-1-of-emitters-produce-over-1000-times-more-co2-than-the-bottom-1

– Gardiner, S. M. (2006). A Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenerational Ethics and the Problem of Moral Corruption. Environmental Values, 15(3,), 397–413.

– Lindsey, R., & Dahlman, L. (2020). Climate change: Global temperature. Climate. Gov, 16.

– Mulligan, T. (2023). Meritocracy. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/meritocracy/

Anomalies are usually triggering for us. Imagine your doctor telling you that there’s an anomaly in your blood test. You would be alarmed, would try to understand the situation, and would look for solutions that alleviate the problem.

Currently, a triggering anomaly that lives in my head rent-free is the climate patterns that we observe. The science is clear that the current average global temperatures and the frequency of the extreme weather events are an anomaly, but why are we not displaying the same sense of urgency as other anomalies do? Is it not triggering enough?

I do not think so. This idea, that we might have an inhabitable planet in the (near) future, is so often iterated in our everyday discourse. We see it in movies, in the news, it pops up in daily conversations with friends, we read about it, write about it… we experience this in all domains of life.

We, as humans, like to look into the future, see a future, and dream of a better future. This desire for imagination and long-term planning is one of the most distinguishing qualities of humans that sets us apart from other species. So, no, this threat should be affecting us deeply, at least on an unconscious level. Then why are we not immediately acting to solve it?

I feel like most of us – at least in our ‘WEIRD’ bubble – are paralyzed by the immensity of the problem. The climate crisis is very intricately woven into the fabric of society: the economics of it, the social aspects, the politics, the injustice, everything. You would think that untangling it, and solving it just by itself, would require a magic wand with unlimited capabilities.

Take a deep breath… Maybe this is okay. Maybe the storm brought about by the winds of climate change is good. They might even pose an opportunity: “climate change may be a perfect moral storm […] its complexity may turn out to be perfectly convenient for us” (Gardiner, 2006). It is an opportunity to solve the rotten part of our society.

We need a massive, I mean massive, shift in our society. It is, right now, normal to blame the current capitalist system, with its massive emphasis on profit and growth, for the sorry state we are in today. Addressing climate change requires rethinking capitalism, to prioritise the well-being of both people and the planet.

I, however, find it daunting to create monsters that seem too big to defeat. And when we say ‘capitalism’ or ‘the system’, aren’t we doing just this? Maybe, it is easier to take down a structure by slowly damaging its pillars. And I have the perfect starting point in mind.

One of the pillars of the current capitalist framework is meritocracy, which is essentially based on free will. A meritocracy “is a society in which influence (of some sort) is possessed on the basis of merit (whatever that means)” (Mulligan, 2023), with a proposed framework for ‘equal opportunities for all’ given that one has free will to work hard. So, when we are rewarded in this system, we feel like we have earned it since we ‘worked very hard for it’, or we ‘have talent’, or we ‘are smart’.

But are these rewards that are so unequally distributed in society really justified? Throughout the last century, our knowledge of human behaviour has increased with psychological science, but this actually has not yet reflected well enough on our beliefs in free will: our science does show that we are inexorably affected by our genes, and the political, economic and socio-cultural climate we get thrown into when we are born, nonetheless we still have a strong – and considering the science, unjustified – belief that we are ‘free’ to make decisions independently of external influences.

Many aspects of our societal system are based on this notion of free will, including meritocracy. And I believe that we need to replace the aspects of our system that are heavily based on free will if we want to undermine capitalism. So what would a society with less belief in free will, and, therefore, meritocracy, mean for the climate crisis?

Well, most of the achievements that we are proud of, and the consumerist lifestyle that we think that we are entitled to, is actually just mere chance: we were born in some part of the world where people gained riches through the exploitation of the others, and not in another where people and their society have been exploited for hundreds of years. Then, logically following from this, billionaires, or even millionaires for that matter, that wreak havoc upon the planet – “Globally, the top 10% of emitters were responsible for almost half of global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021” (Cozzi et al., 2023) – should not exist, they are simply a policy failure and an ugly reminder of brutal inequalities.

On a more system-level, our desire for never-ending economic growth needs to change, and less belief in free will can actually help this transition. This is because the current system relies upon its individuals to have a productivity-maximising mentality, which comes as a package deal with meritocracy and free will, since one usually needs to choose to ‘grind’ in order to become successful. In return, thanks to its well-behaved hard-working parts – that’s us –, the economy keeps growing with an undying appetite, which in turn exacerbates the climate crisis.

The funny thing is, most of humanity is not really happy with the burden of this belief in free will either. This is because there are actually two sides to this: yes, it does suggest that you are responsible for your own happiness, but it also automatically entails that if you have not achieved ‘your dreams’ – which, by the way, are a product of our times in and of themselves anyways – the fault is on you. Which is completely ridiculous considering all the factors that you are not in control of. This whole thing is a great way to shift the attention from the structural inequalities and injustices to the individual, which further perpetuates these structural inequalities and injustices.

If we ease this burden, then we ease the pressure for ourselves to become ‘better’ agents of the system. Instead of striving for individual success, we can give more importance to spending time with loved ones and feelings of community. Instead of promoting ambition, greed, and consumerism, we can promote kindness, caring, and enjoyment of life. This new way of existence will in turn alleviate the climate crisis.

Finally, rethinking free will also allows us to consider our place in the world. Most religions that have been massively important in shaping our thinking throughout history tend to put humans as the centre of the universe, indirectly giving us the right for environmental destruction and mass extinction simply because everything was created for us. If individuals are not ultimately responsible for their choices and actions due to a lack of free will, it challenges the traditional notions of deserving reward or punishment in an afterlife. Hence, getting rid of our belief in complete free will would also entail killing God and his heavens, but, well, who cares about it if we hella hot down here.

The idea of the necessity of a system change to tackle the climate crisis is not new. However, how we need to rethink free will, considering its massive importance for this system to function, is never addressed. Maybe the climate anomalies are just symptoms of a disease in our system of thinking and beliefs. And it is always good to have the right diagnosis.