Imagine this – one day, you wake up to find yourself in a place where your status in society is determined arbitrarily, and that status is decisive of whether you have access to resources. While you probably didn’t have to do much imagining, Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s El Hoyo strips this reality to its core. El Hoyo, or the hole in English, is a multi-level prison. Each level has one cell, and there are two inmates to a cell. In the center of the cell, there is a hole. The hole is not only large enough to peer into the lives of your upstairs and downstairs ‘neighbors’, but is also plenty large enough for a person to fall, or jump through.

Each day, starting at the first and uppermost level, a platform descends through the hole, presenting an artfully prepared gourmet spread. As the platform makes its way down the hole, those at the higher levels are quick to devour the daily feast, leaving those below to rummage through their scraps. However, an inmate’s place on their level is never secure. Inmates are randomly assigned to a different level each month, which, funnily enough, offers more class mobility than the real world. When inmates wake up on a new level, they don’t have to do much guessing; to their delight, or dismay, their floor number is engraved into the wall. The intricacies of this premise are revealed throughout the movie, forming an obvious, but tidy class commentary.

Initially, the protagonist, Goreng, played by Iván Massagué, tries to advocate for rationing the food. Theoretically, if everybody takes what they need, there should be enough for everyone. After all, those at the higher levels had lived on the lower levels in previous months, so they not only understand that their greed leads to starvation of others, but have also been on the receiving end of it. The switching of the levels only perpetuates the cycle, because the possibility that one could end up on a much lower level next month means that inmates should take what they can while they can. They know that when they end up on a lower level, those above will do the same. It is quite literally a prisoner’s dilemma. Interestingly, Gaztelu-Urrutia implies that ignorance is not what leads to greed, rather it is the structure of the system itself. Inmates must either participate or kill themselves, either indirectly through starvation, or by directly throwing themselves into the hole. Even if you’re on level one, you’re still in a prison.

While the analogy is by no means subtle, its transparency reads like a message in and of itself. This bleakness finds its way into every aspect of the film – the cinematography, the characterization, and most strikingly in its graphic depictions of violence. In a time where class divides are becoming increasingly clear-cut, why should art reflect any differently? The starvation, the violence, and the suffering are all exposed as being inevitable byproducts of the prison system. Our current economic systems supposedly promote prosperity, yet they bear an uncanny resemblance to El Hoyo, specifically designed as a punishment.

Although the film was shot before the Covid-19 crisis, the global state of emergency has only deepened pre-existing social divides. While celebrities are likening self-quarantine in a $15 million mansion to “being in jail” (Lee, 2020), millions are being pushed into extreme poverty due to the crisis (Mahler, Lakner, Aguilar, & Wu, 2020). It’s a little on the nose if you ask me. Admittedly, it may not be the best time to hit the streets demanding structural change. With that being said, we are reaching a tipping point where it is becoming much harder to ignore the fact that we benefit from a system that harms others. With the topic of economic inequality being pushed into the mainstream, El Hoyo shows us that it’s time we talk about social class in plain terms.

Directed by: Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia

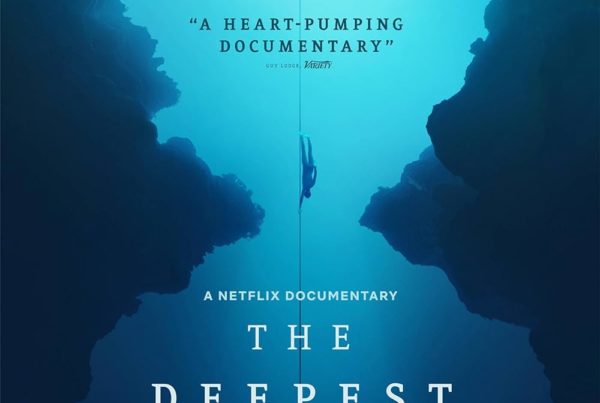

This movie is out now on Netflix.

References

– Lee, A. (2020, April 9). Ellen DeGeneres sparks backlash after joking that self-quarantine is like ‘being in jail’. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/08/entertainment/ellen-degeneres-quarantine-jail-trnd/index.html

– Gaztelu-Urrutia, G., (2019) El Hoyo, Netflix, Retrieved April 16, 2020, from https://www.netflix.com/title/81128579

– Mahler, D. G., Lakner, C., Aguilar, A. C., & Wu, H. (2020, April 20). The impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) on global poverty: Why Sub-Saharan Africa might be the region hardest hit. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/impact-covid-19-coronavirus-global-poverty-why-sub-saharan-africa-might-be-region-hardest

Imagine this – one day, you wake up to find yourself in a place where your status in society is determined arbitrarily, and that status is decisive of whether you have access to resources. While you probably didn’t have to do much imagining, Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s El Hoyo strips this reality to its core. El Hoyo, or the hole in English, is a multi-level prison. Each level has one cell, and there are two inmates to a cell. In the center of the cell, there is a hole. The hole is not only large enough to peer into the lives of your upstairs and downstairs ‘neighbors’, but is also plenty large enough for a person to fall, or jump through.

Each day, starting at the first and uppermost level, a platform descends through the hole, presenting an artfully prepared gourmet spread. As the platform makes its way down the hole, those at the higher levels are quick to devour the daily feast, leaving those below to rummage through their scraps. However, an inmate’s place on their level is never secure. Inmates are randomly assigned to a different level each month, which, funnily enough, offers more class mobility than the real world. When inmates wake up on a new level, they don’t have to do much guessing; to their delight, or dismay, their floor number is engraved into the wall. The intricacies of this premise are revealed throughout the movie, forming an obvious, but tidy class commentary.

Initially, the protagonist, Goreng, played by Iván Massagué, tries to advocate for rationing the food. Theoretically, if everybody takes what they need, there should be enough for everyone. After all, those at the higher levels had lived on the lower levels in previous months, so they not only understand that their greed leads to starvation of others, but have also been on the receiving end of it. The switching of the levels only perpetuates the cycle, because the possibility that one could end up on a much lower level next month means that inmates should take what they can while they can. They know that when they end up on a lower level, those above will do the same. It is quite literally a prisoner’s dilemma. Interestingly, Gaztelu-Urrutia implies that ignorance is not what leads to greed, rather it is the structure of the system itself. Inmates must either participate or kill themselves, either indirectly through starvation, or by directly throwing themselves into the hole. Even if you’re on level one, you’re still in a prison.

While the analogy is by no means subtle, its transparency reads like a message in and of itself. This bleakness finds its way into every aspect of the film – the cinematography, the characterization, and most strikingly in its graphic depictions of violence. In a time where class divides are becoming increasingly clear-cut, why should art reflect any differently? The starvation, the violence, and the suffering are all exposed as being inevitable byproducts of the prison system. Our current economic systems supposedly promote prosperity, yet they bear an uncanny resemblance to El Hoyo, specifically designed as a punishment.

Although the film was shot before the Covid-19 crisis, the global state of emergency has only deepened pre-existing social divides. While celebrities are likening self-quarantine in a $15 million mansion to “being in jail” (Lee, 2020), millions are being pushed into extreme poverty due to the crisis (Mahler, Lakner, Aguilar, & Wu, 2020). It’s a little on the nose if you ask me. Admittedly, it may not be the best time to hit the streets demanding structural change. With that being said, we are reaching a tipping point where it is becoming much harder to ignore the fact that we benefit from a system that harms others. With the topic of economic inequality being pushed into the mainstream, El Hoyo shows us that it’s time we talk about social class in plain terms.

Directed by: Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia

This movie is out now on Netflix.