Parents want their children to do well in school, with some feeling that they must compete against each other or against the clock to become the best. Academic achievement is valued highly throughout childhood because it sets children up for better opportunities in the future. While some parents end up stressing achievement too much, others participate in their children’s school life too little. In this article, I explore how demanding high achievements can backfire and why active involvement is more likely to help children succeed academically.

Parents want their children to do well in school, with some feeling that they must compete against each other or against the clock to become the best. Academic achievement is valued highly throughout childhood because it sets children up for better opportunities in the future. While some parents end up stressing achievement too much, others participate in their children’s school life too little. In this article, I explore how demanding high achievements can backfire and why active involvement is more likely to help children succeed academically.

Photo by Ilo Taimisto

Photo by Ilo Taimisto

The idea that grades will decide one’s future makes parents very preoccupied with achievement. Efforts to motivate and keep a child on the right track toward a certain goal (e.g. being admitted to a good university/ entering a desired profession) can become a big burden for children.

Achievement pressure is one of the main sources of worry in school-aged children (Silverman et al., 1995). A survey of tens of thousands of American children showed more than 60% of middle school children and more than 85% of high school children are stressed by academic demands (Villeneuve, Conner, Selby,& Pope, 2019). Part of this stress can be attributed to parental achievement pressure, which broadly entails demanding children to maintain high performance in school (Ablard & Parker, 1997). For example, in a study on Indian adolescents, more than two-thirds of students experienced parental achievement pressure, most commonly by comparing their performance with the best performer in class (Deb et al., 2015).

Parents who put pressure on academic achievement (despite children performing well) have children who experience more academic stress and more symptoms of depression and anxiety (Haspolat & Yalçın, 2023). Some children who feel pressured to excel academically have more test anxiety (Ringeisen & Raufelder, 2015) and end up procrastinating on their academic tasks more (주희박, 2021). Moreover, parental achievement pressure can paradoxically lead to worse achievement. Ciciolla et. al. (2017) found that a lower emphasis on achievement was associated with healthier outcomes for children and better school performance, while the highest levels of school maladjustment were found when both achievement pressure and criticism were high.

“High academic hopes for one’s children do not have to manifest as achievement pressure.”

Interviews with Norwegian adolescents revealed two types of parental achievement pressure (Eriksen, 2020). One group described their parents’ achievement pressure as explicit, with rewards for good grades (i.e., receiving more pocket money) and sanctions for poor performance (i.e., forbidding video games, taking the phone away, or asking to give pocket money back). This group indicated that they felt the pressure to achieve was the cause of their mental health issues: tiredness, sadness, depression, and sleep problems. A second group described their parents’ expectations as implicit, mentioning that they were never pushed to work hard, but always felt their parents valued education very much. They thought that the pressure that leads to negative psychological symptoms came from their own ambitions.

High academic hopes for one’s children do not have to manifest as achievement pressure. Instead, it can translate to increased parental involvement in their children’s schooling. Parental involvement covers various actions that parents can take to support their children’s learning (Boonk et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2016). For example:

- Participating in school/educational activities with the child

- Being interested in children’s education-related concerns

- Reading books

- Encouraging participation in problem-solving and decision-making

- Encouraging learning

- Limiting TV time

- Volunteering at school

- Attending parent-teacher conferences

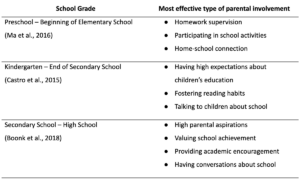

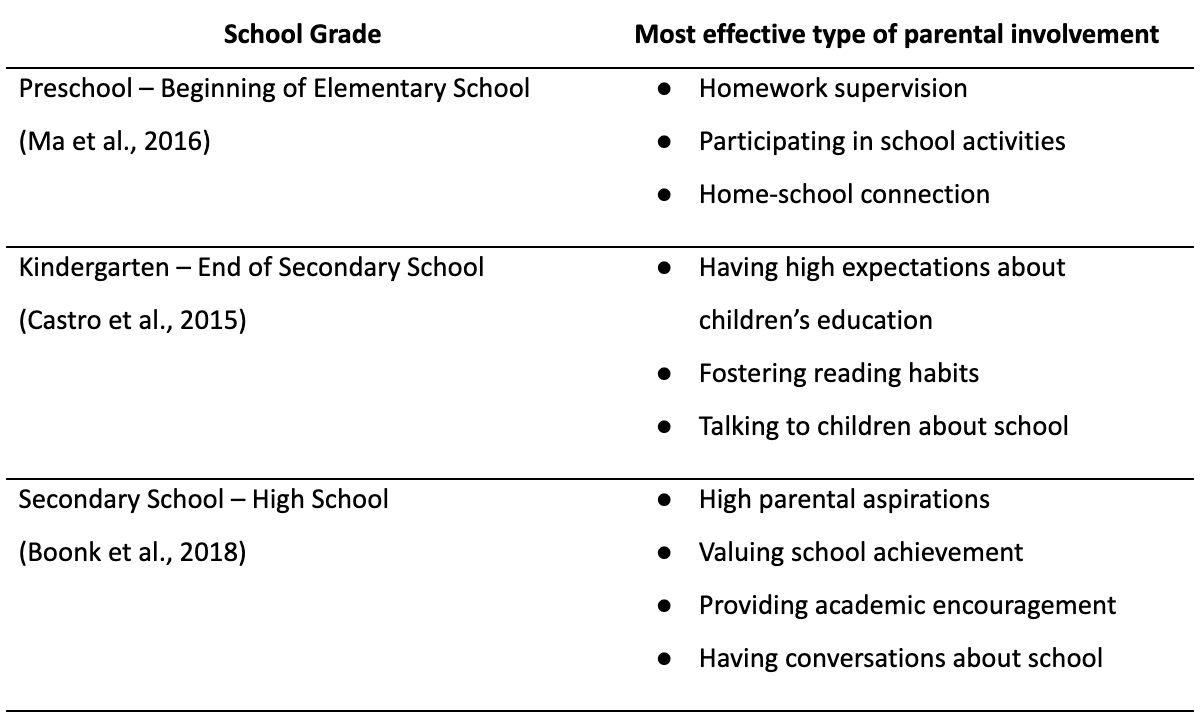

From preschool to high school, children whose parents are more involved have better academic performance (Boonk et al. 2018, Castro et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2016). In addition, effect sizes of this positive relation tend to increase with age (Castro et al., 2015, Ma et. al, 2016) and different types of parental involvement are the most effective for supporting school achievement depending on the school grade of children (Boonk et al., 2018; Castro et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016).

Thus, compared to younger children who need more concrete activities, older children gain more if their parents have a positive attitude about education and encourage them to persevere.

“pressure creates a transactional relationship, in which children are valued through their school achievements and their fun activities are conditional on doing well”

It seems logical that involvement is better than pressure. Still, it is hard to reconcile that having high aspirations for children is good, but achievement pressure is not. How can we draw the line between them? The literature does not establish a clear boundary where valuing school achievement turns into pressure but indicates that putting a high price on education comes together with more concrete involvement. It is more about “you can do this and I’m here to help” than “you must do this and I’m here to sanction you”. Moreover, as the interviews with Norwegian teenagers show, valuing education can be perceived as pressure to perform by some – thus parents should be careful in communicating what it is that they hope for: is it good grades at all costs or is it having a positive attitude about learning and developing oneself?

To my mind, pressure creates a transactional relationship, in which children are valued through their school achievements and their fun activities are conditional on doing well. It also comes with criticism and seems to be less about the value of education in and of itself, and more about performing competitively. Indeed, achievement pressure is less detrimental when children see it as parents’ attempt to support them, rather than criticize them (Jiang et al., 2011). Ultimately, there are many ways in which parents can get involved in children’s education which are both good for their academic performance and for their well-being. <<

References

– 주희박. (2021). The effect of parental academic achievement pressure perceived by middle school students on academic procrastination: The mediating role of evaluative concerns perfectionism. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 42(5), 537-551.

– Ablard, K. E., & Parker, W. D. (1997). Parents’ achievement goals and perfectionism in their academically talented children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(6), 651-667.

– Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

– Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

– Ciciolla, L., Curlee, A. S., Karageorge, J., & Luthar, S. S. (2017). When Mothers and Fathers Are Seen as Disproportionately Valuing Achievements: Implications for Adjustment Among Upper Middle Class Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(5), 1057–1075. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0596-x

– Deb, S., Strodl, E., & Sun, J. (2015). Academic stress, parental pressure, anxiety and mental health among Indian high school students. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 5(1), 26-34. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijpbs.20150501.04

– Eriksen, I. M. (2020). Class, parenting and academic stress in Norway: Middle-class youth on parental pressure and mental health. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1716690

– Haspolat, N. K., & Yalçın, İ. (2023). Psychological symptoms in high achieving students: The multiple mediating effects of parental achievement pressure, perfectionism, and academic expectation stress. Psychology in the Schools, 60(11), 4721-4739.

– Jiang, Y. H., Yau, J., Bonner, P., & Chiang, L. (2011). The role of perceived parental autonomy support in academic achievement of Asian and Latin American adolescents.

– Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Hu, S., & Yuan, J. (2016). A Meta-Analysis of the Relationship Between Learning Outcomes and Parental Involvement During Early Childhood Education and Early Elementary Education. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 771–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1

– Ringeisen, T., & Raufelder, D. (2015). The interplay of parental support, parental pressure and test anxiety–gender differences in adolescents. Journal of adolescence, 45, 67-79.

– Silverman, W. K., La Greca, A. M., & Wasserstein, S. (1995). What do children worry about? Worries and their relation to anxiety. Child development, 66(3), 671-686.

The idea that grades will decide one’s future makes parents very preoccupied with achievement. Efforts to motivate and keep a child on the right track toward a certain goal (e.g. being admitted to a good university/ entering a desired profession) can become a big burden for children.

Achievement pressure is one of the main sources of worry in school-aged children (Silverman et al., 1995). A survey of tens of thousands of American children showed more than 60% of middle school children and more than 85% of high school children are stressed by academic demands (Villeneuve, Conner, Selby,& Pope, 2019). Part of this stress can be attributed to parental achievement pressure, which broadly entails demanding children to maintain high performance in school (Ablard & Parker, 1997). For example, in a study on Indian adolescents, more than two-thirds of students experienced parental achievement pressure, most commonly by comparing their performance with the best performer in class (Deb et al., 2015).

Parents who put pressure on academic achievement (despite children performing well) have children who experience more academic stress and more symptoms of depression and anxiety (Haspolat & Yalçın, 2023). Some children who feel pressured to excel academically have more test anxiety (Ringeisen & Raufelder, 2015) and end up procrastinating on their academic tasks more (주희박, 2021). Moreover, parental achievement pressure can paradoxically lead to worse achievement. Ciciolla et. al. (2017) found that a lower emphasis on achievement was associated with healthier outcomes for children and better school performance, while the highest levels of school maladjustment were found when both achievement pressure and criticism were high.

“High academic hopes for one’s children do not have to manifest as achievement pressure.”

Interviews with Norwegian adolescents revealed two types of parental achievement pressure (Eriksen, 2020). One group described their parents’ achievement pressure as explicit, with rewards for good grades (i.e., receiving more pocket money) and sanctions for poor performance (i.e., forbidding video games, taking the phone away, or asking to give pocket money back). This group indicated that they felt the pressure to achieve was the cause of their mental health issues: tiredness, sadness, depression, and sleep problems. A second group described their parents’ expectations as implicit, mentioning that they were never pushed to work hard, but always felt their parents valued education very much. They thought that the pressure that leads to negative psychological symptoms came from their own ambitions.

High academic hopes for one’s children do not have to manifest as achievement pressure. Instead, it can translate to increased parental involvement in their children’s schooling. Parental involvement covers various actions that parents can take to support their children’s learning (Boonk et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2016). For example:

- Participating in school/educational activities with the child

- Being interested in children’s education-related concerns

- Reading books

- Encouraging participation in problem-solving and decision-making

- Encouraging learning

- Limiting TV time

- Volunteering at school

- Attending parent-teacher conferences

From preschool to high school, children whose parents are more involved have better academic performance (Boonk et al. 2018, Castro et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2016). In addition, effect sizes of this positive relation tend to increase with age (Castro et al., 2015, Ma et. al, 2016) and different types of parental involvement are the most effective for supporting school achievement depending on the school grade of children (Boonk et al., 2018; Castro et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016).

Thus, compared to younger children who need more concrete activities, older children gain more if their parents have a positive attitude about education and encourage them to persevere.

“pressure creates a transactional relationship, in which children are valued through their school achievements and their fun activities are conditional on doing well”

It seems logical that involvement is better than pressure. Still, it is hard to reconcile that having high aspirations for children is good, but achievement pressure is not. How can we draw the line between them? The literature does not establish a clear boundary where valuing school achievement turns into pressure but indicates that putting a high price on education comes together with more concrete involvement. It is more about “you can do this and I’m here to help” than “you must do this and I’m here to sanction you”. Moreover, as the interviews with Norwegian teenagers show, valuing education can be perceived as pressure to perform by some – thus parents should be careful in communicating what it is that they hope for: is it good grades at all costs or is it having a positive attitude about learning and developing oneself?

To my mind, pressure creates a transactional relationship, in which children are valued through their school achievements and their fun activities are conditional on doing well. It also comes with criticism and seems to be less about the value of education in and of itself, and more about performing competitively. Indeed, achievement pressure is less detrimental when children see it as parents’ attempt to support them, rather than criticize them (Jiang et al., 2011). Ultimately, there are many ways in which parents can get involved in children’s education which are both good for their academic performance and for their well-being.