Through the internet, pornography has become increasingly accessible to everyone, everywhere. While a number of negative outcomes have been linked to pornography consumption already, recent research also included another possible mediating variable: Religion.

Through the internet, pornography has become increasingly accessible to everyone, everywhere. While a number of negative outcomes have been linked to pornography consumption already, recent research also included another possible mediating variable: Religion.

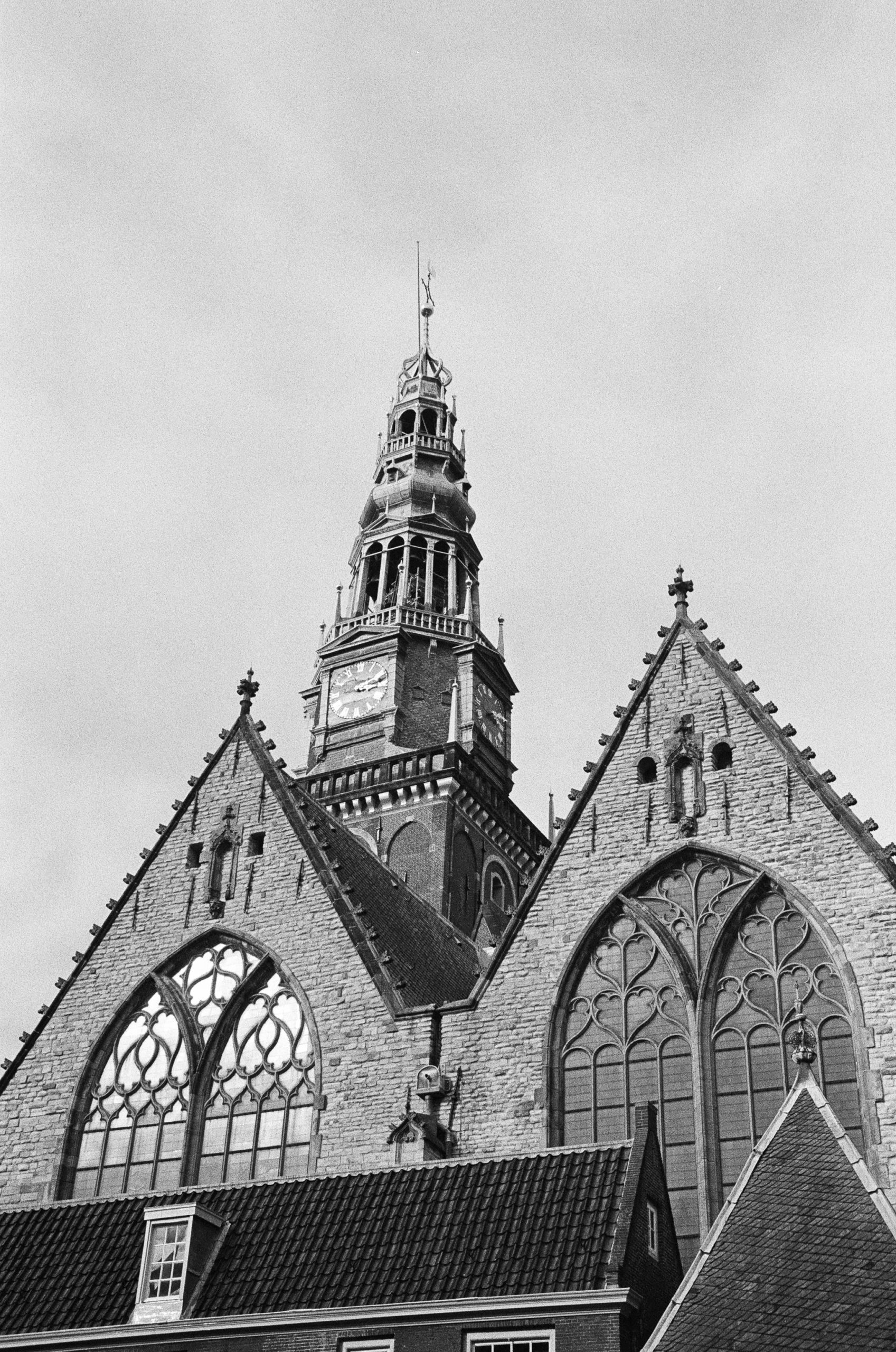

Photo by Sarah Laszlo

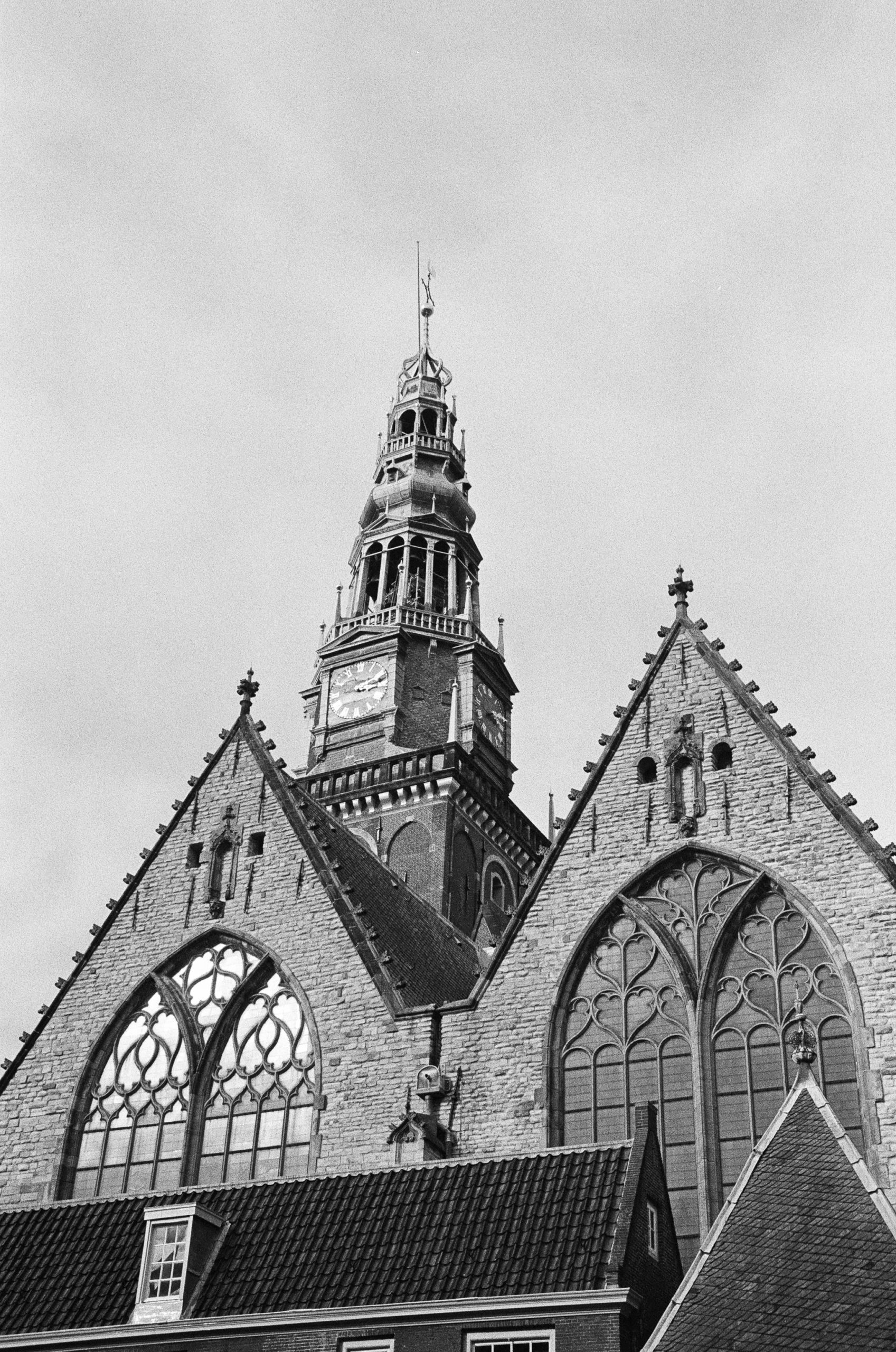

Photo by Sarah Laszlo

Most religions endorse sexual purity and expect their followers to not indulge in sexual practices like prostitution, pornography and sometimes, even premarital sex. Taking this into consideration, it is to be expected that people devoted to their religion are less likely to watch pornography than others. While some studies are indeed in line with this finding, other studies report the difference to non-religious people to be not as great considering their moral stance (Perry, 2018). The same study also found that greater religious service attendance and prayer frequency were predictive of American men (but not women) to affirm that viewing pornography is “always morally wrong” while still viewing it in the last year. Having established that there is a difference between moral standpoints and actual behavior, the question arises how someone who is truly devoted to the morals and rules of their religion copes with this discrepancy and the guilt that comes with it.

The short answer is: coping is not going well. This great moral incongruence between practice and theory produces a cognitive dissonance which arises when someone’s values and behavior don’t match. Consequently, people try to adjust either their beliefs and values, or their behavior in order to reduce this dissonance they are feeling. Since there is still a number of people that watch pornography but also identify with their religious beliefs, this moral incongruence may manifest itself in a different way. Grubbs & Perry (2019) found exactly that: In religious participants who reported moral incongruence regarding their views on pornography, greater psychological distress in general, and other problems like decreased marital quality were assessed. Patterson & Price (2012) discovered a phenomenon which they called the “happiness gap”. They established that while reported pornography consumption is correlated with lower happiness on average, this relationship is the strongest among individuals who regularly attend a religious denomination with strong attitudes against the use of pornography. Sexual satisfaction was also more negatively associated with frequency of pornography use in men with stronger ties to their conventional religion (Perry & Whitehead, 2019). Even a greater likelihood for depressive symptoms was measured in conflicted porn viewers (Perry, 2018).

Another very interesting finding demonstrates how religious pornography viewers perceive themselves: Self-perceived pornography addiction was higher among religious consumers. When measuring their actual pornography use, no above average use or dysfunctional behaviour, like it would be present in addictive behaviour, was found (Grubbs et al., 2015). In this study, greater negative attitudes also predicted greater perceived addiction. In other words, being so convinced of their moral standpoint and the taboo their religion is prescribing, they see their sexual purity violated. Consequently, they end up showing harsh reactions and pathological interpretations.

Having seen that a number of negative outcomes are associated with pornography use in religious individuals, another question pops up: How to deal with this? In the past, banning pornography has not been the solution to prevent these adverse outcomes of pornography use and surely, heightened feelings of shame and fear would make the problem even worse. In general, one might also question if taboos around sex in general are a helpful guideline for behavior (in this case, provided by their religion) or more of an obstacle for someone’s well-being and successful development, especially looking at the research presented here. But since the rules and interpretations of religions are not easily modified or changed, no development can be expected in that area soon. Overall, future research into this topic is definitely necessary to determine how negative effects can be foreseen and prevented, what the risk factors are and what the exact causes of this observed relationship between pornography use and religiosity are.

References

– Grubbs, J. B., & Perry, S. L. (2019). Moral incongruence and pornography use: A critical review and integration. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1427204

– Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Hook, J. N., & Carlisle, R. D. (2015). Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z

– Patterson, R., & Price, J. (2012). Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: Does pornography impact the actively religious differently?. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(1), 79-89.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01630.x

– Perry, S. L. (2018). Not practicing what you preach: Religion and incongruence between pornography beliefs and usage. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 369-380.https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1333569

– Perry, S. L. (2018). Pornography use and depressive symptoms: Examining the role of moral incongruence. Society and Mental Health, 8(3), 195-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869317728373

– Perry, S. L., & Whitehead, A. L. (2019). Only bad for believers? Religion, pornography use, and sexual satisfaction among American men. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 50-61.https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1423017

Most religions endorse sexual purity and expect their followers to not indulge in sexual practices like prostitution, pornography and sometimes, even premarital sex. Taking this into consideration, it is to be expected that people devoted to their religion are less likely to watch pornography than others. While some studies are indeed in line with this finding, other studies report the difference to non-religious people to be not as great considering their moral stance (Perry, 2018). The same study also found that greater religious service attendance and prayer frequency were predictive of American men (but not women) to affirm that viewing pornography is “always morally wrong” while still viewing it in the last year. Having established that there is a difference between moral standpoints and actual behavior, the question arises how someone who is truly devoted to the morals and rules of their religion copes with this discrepancy and the guilt that comes with it.

The short answer is: coping is not going well. This great moral incongruence between practice and theory produces a cognitive dissonance which arises when someone’s values and behavior don’t match. Consequently, people try to adjust either their beliefs and values, or their behavior in order to reduce this dissonance they are feeling. Since there is still a number of people that watch pornography but also identify with their religious beliefs, this moral incongruence may manifest itself in a different way. Grubbs & Perry (2019) found exactly that: In religious participants who reported moral incongruence regarding their views on pornography, greater psychological distress in general, and other problems like decreased marital quality were assessed. Patterson & Price (2012) discovered a phenomenon which they called the “happiness gap”. They established that while reported pornography consumption is correlated with lower happiness on average, this relationship is the strongest among individuals who regularly attend a religious denomination with strong attitudes against the use of pornography. Sexual satisfaction was also more negatively associated with frequency of pornography use in men with stronger ties to their conventional religion (Perry & Whitehead, 2019). Even a greater likelihood for depressive symptoms was measured in conflicted porn viewers (Perry, 2018).

Another very interesting finding demonstrates how religious pornography viewers perceive themselves: Self-perceived pornography addiction was higher among religious consumers. When measuring their actual pornography use, no above average use or dysfunctional behaviour, like it would be present in addictive behaviour, was found (Grubbs et al., 2015). In this study, greater negative attitudes also predicted greater perceived addiction. In other words, being so convinced of their moral standpoint and the taboo their religion is prescribing, they see their sexual purity violated. Consequently, they end up showing harsh reactions and pathological interpretations.

Having seen that a number of negative outcomes are associated with pornography use in religious individuals, another question pops up: How to deal with this? In the past, banning pornography has not been the solution to prevent these adverse outcomes of pornography use and surely, heightened feelings of shame and fear would make the problem even worse. In general, one might also question if taboos around sex in general are a helpful guideline for behavior (in this case, provided by their religion) or more of an obstacle for someone’s well-being and successful development, especially looking at the research presented here. But since the rules and interpretations of religions are not easily modified or changed, no development can be expected in that area soon. Overall, future research into this topic is definitely necessary to determine how negative effects can be foreseen and prevented, what the risk factors are and what the exact causes of this observed relationship between pornography use and religiosity are.