‘Speak a new language so that the world will be a new world.’, says Rumi. Just like he says, the languages we speak seem to play an important role in how we experience the world.

‘Speak a new language so that the world will be a new world.’, says Rumi. Just like he says, the languages we speak seem to play an important role in how we experience the world.

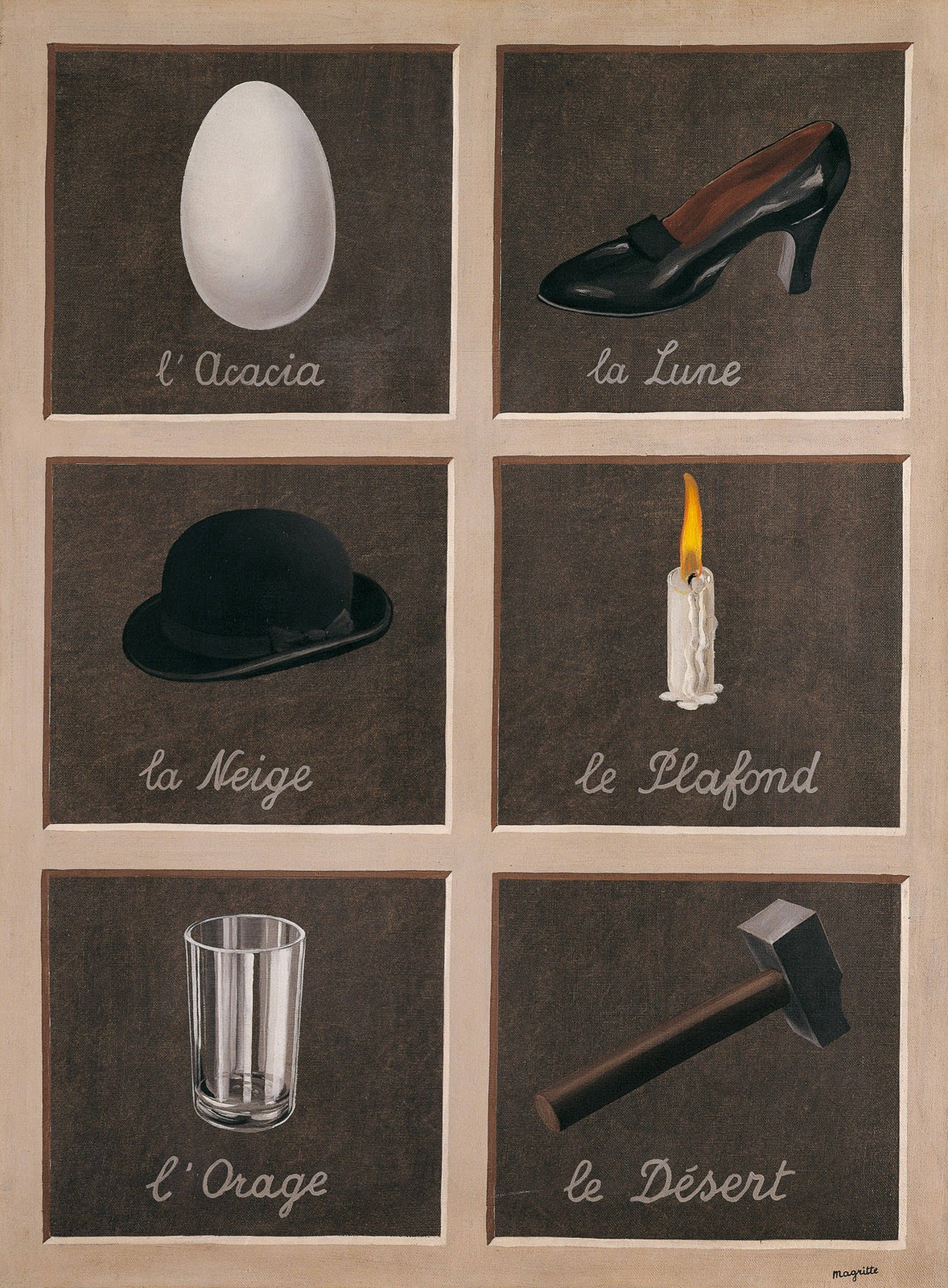

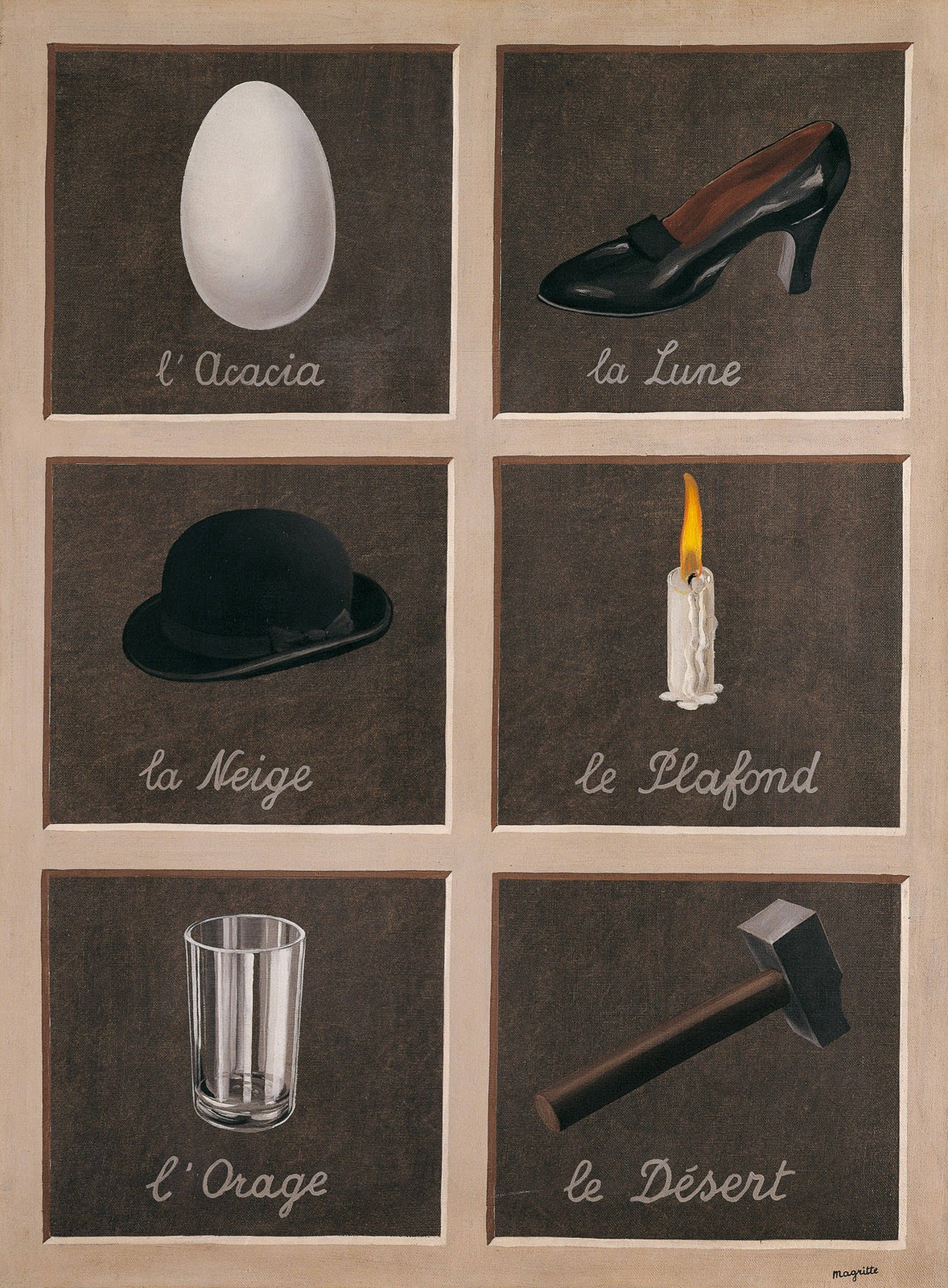

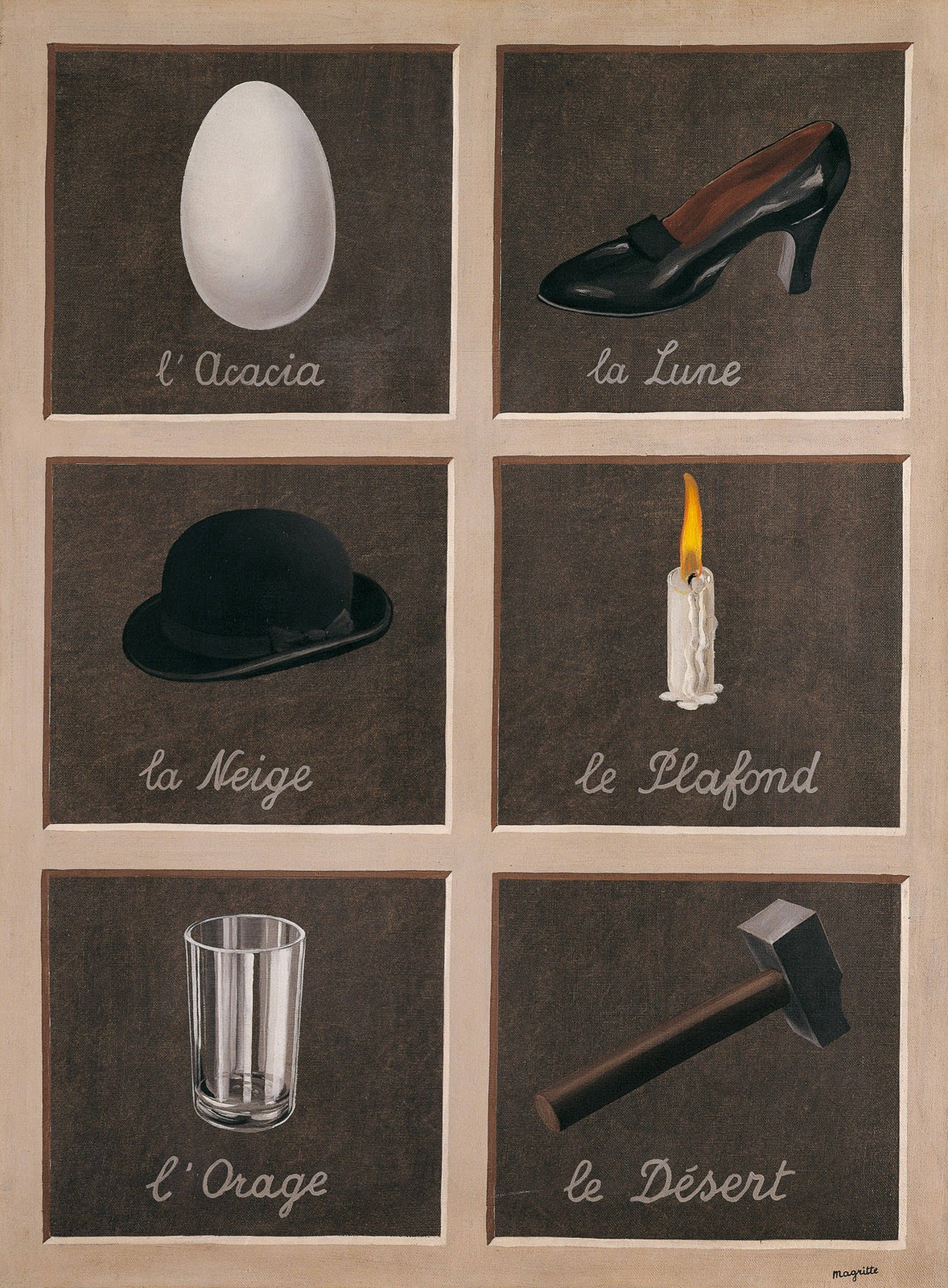

La Clef des Songes by René Magritte

La Clef des Songes by René Magritte

We acquire our native languages in such a natural process that we don’t even remember how it happened. Once we start speaking, we don’t spend time choosing our words, and our brain generates sentences fairly quickly. It is one of the most natural things we do in our daily lives. Yet, the powerful role that it plays in our perception, and consequently our experience of the world, is quite impressive. From how we see colors to how we experience emotions, languages influence our thought patterns and shape the world we see. In other words, it is the lens through which we view and experience the world.

Let’s take colors as our first example. Although in English we can express all shades of blue with one word, Russian speakers need to make a distinction between dark blue (siniy) and light blue (goluboy) as they don’t have a word that covers both shades. In one study (Winawer et al., 2007), researchers questioned whether this lexical difference influences the speakers’ color perception as well. Participants were presented with blue stimuli that have different shades and were asked to discriminate the colors as fast as possible. Russian speakers were faster to discriminate between a light shade and a dark shade (different linguistic categories), compared to two light or two dark shades (same linguistic category). It was then investigated whether the same advantage would be present in a dual task. While still doing the color discrimination task, in one condition participants were asked to silently rehearse random digit strings (verbal dual task) and in the other condition, they were asked to retain a spatial pattern in their mind (spatial dual task). Interestingly, although the advantage was still present in a dual spatial task, it disappeared when participants were asked to do a dual verbal task. This advantage was not present at all for English speakers. The loss of this advantage in an additional verbal task indicates that Russian speakers acquired this ability through a verbal process in the first place. Another example can be found in the Zuñi language, the language of native New Mexicans. This language doesn’t have different words for the color yellow and orange as we have in English. And much like in the previous example, a study done back in 1957 (Brown and Lenneberg, 1957) found that its speakers have difficulty distinguishing those two colors. Of course, these findings do not mean that Zuñi speakers don’t experience a difference between orange and yellow or that English speakers are unable to distinguish the shades of blue. Rather, it means that speakers of different languages have distinct eyes looking at the world. While the English-speaking world sees shades as an extra detail, it is the most natural thing for Russian speakers to describe the shades in their daily conversations.

“once we find a specific word for a feeling, that somewhat superficial feeling becomes a precise concept in our mind”

Beyond having the power to influence our color perception, language can also have an impact on how we express our emotions. For example, Uitwaaien is a Dutch word for taking a walk in the wind to clear one’s head. Probably inspired by their windy weather, Dutch people see this as a refreshing activity and even made a word for it. On a more melancholic note, natsukashii, a Japanese word, means feeling a nostalgic longing for the past while also feeling grateful for those memories. It defines the bittersweet feeling of missing the happy memories in our past. This time from German, Sehnsucht is a word to express the intense desire for alternative paths and states of life. Picture the most beautiful sunset you watched, accompanied by the refreshing feeling of crispy weather. Longing to go back to that exact moment, is what German speakers call Sehnsucht. Another word, retrouvailles, is a French word that (literally) means ‘reunion’ in English. However, this word expresses more than a simple reunion. Retrouvailles implies that this reunion is happening with loved ones after a long time of being away from each other, it expresses the powerful joy in that moment.

These feelings are surely familiar to all of us. We all had that incredible moment of retrouvailles, experienced uitwaaien around Amsterdam (probably during lockdown), or felt the natsukashii while thinking about our good memories. But what makes it interesting is that once we find a specific word for a feeling, that somewhat superficial feeling becomes a precise concept in our mind. The now-defined emotion becomes more expressible and its experience gets richer. Imagine not having the word ‘beautiful’, how would we define the people (and the things) we find beautiful? We would still feel it in some way for sure, but how intense would it be? Or imagine not having a specific word for the concept of love; feeling of affection, caring deeply for someone (or something), being supportive, and all the other positive feelings that come to mind when ‘love’ is mentioned. The single word love encompasses it all, gives people a way to define their feelings, express themselves, and even write books and songs about it. Consequently, it enriches the experience of that emotion and makes it more meaningful.

“there are many other worlds to discover by learning new languages”

Besides enriching our experience of emotions, these words also change the way we perceive the world, just as it happens with the color words. Maybe Wittgenstein went a bit far by saying ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my mind. All I know is what I have words for.’ because there is no doubt, we still experience more than what we have words for. Zuñi speakers sure experience orange and yellow, and non-French speakers sure feel joyful seeing their friends after a long time. However, Wittgenstein was still right in a way. Our mind tends to draw our attention towards the concepts and the emotions that we already have words for. It focuses on the aspects of the world that we already know how to define, and the rest goes unnoticed.

Our language shapes our perception. Different languages have different perspectives on the world, and they live in different worlds. When I learned French and finally felt like I mastered it enough to understand their literature, I felt like I was given a key to the world of Montaigne, Camus, and Sartre. I read the translations of their books before but reading them in the same way the writers see the world and the way they define it with their words, was quite different from the translations. This experience made me realize that a translation between two languages is no different than switching between two worlds. No matter how good the translation is, there is always something that gets lost and is missed by foreign readers.

To conclude, the languages we speak have the power to shape the way we experience the world. We can even go as far as to say that languages are powerful enough to create different worlds. This is not to say that our languages limit us, as Wittgenstein put it. Rather, it means that there are many other worlds to discover by learning new languages. I now have enough reasons to learn German to read Zweig and Goethe, or even Russian to read Gogol and Dostoyevsky in their own worlds.<<

References

– Brown, R. W., & Lenneberg, E. H. (1954). A study in language and cognition. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 49(3), 454–462.

– Lomas, Tim. (2020). Lexicography (listed by language).

– Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A. R., & Boroditsky, L. (2007). Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 104(19), 7780-7785.

We acquire our native languages in such a natural process that we don’t even remember how it happened. Once we start speaking, we don’t spend time choosing our words, and our brain generates sentences fairly quickly. It is one of the most natural things we do in our daily lives. Yet, the powerful role that it plays in our perception, and consequently our experience of the world, is quite impressive. From how we see colors to how we experience emotions, languages influence our thought patterns and shape the world we see. In other words, it is the lens through which we view and experience the world.

Let’s take colors as our first example. Although in English we can express all shades of blue with one word, Russian speakers need to make a distinction between dark blue (siniy) and light blue (goluboy) as they don’t have a word that covers both shades. In one study (Winawer et al., 2007), researchers questioned whether this lexical difference influences the speakers’ color perception as well. Participants were presented with blue stimuli that have different shades and were asked to discriminate the colors as fast as possible. Russian speakers were faster to discriminate between a light shade and a dark shade (different linguistic categories), compared to two light or two dark shades (same linguistic category). It was then investigated whether the same advantage would be present in a dual task. While still doing the color discrimination task, in one condition participants were asked to silently rehearse random digit strings (verbal dual task) and in the other condition, they were asked to retain a spatial pattern in their mind (spatial dual task). Interestingly, although the advantage was still present in a dual spatial task, it disappeared when participants were asked to do a dual verbal task. This advantage was not present at all for English speakers. The loss of this advantage in an additional verbal task indicates that Russian speakers acquired this ability through a verbal process in the first place. Another example can be found in the Zuñi language, the language of native New Mexicans. This language doesn’t have different words for the color yellow and orange as we have in English. And much like in the previous example, a study done back in 1957 (Brown and Lenneberg, 1957) found that its speakers have difficulty distinguishing those two colors. Of course, these findings do not mean that Zuñi speakers don’t experience a difference between orange and yellow or that English speakers are unable to distinguish the shades of blue. Rather, it means that speakers of different languages have distinct eyes looking at the world. While the English-speaking world sees shades as an extra detail, it is the most natural thing for Russian speakers to describe the shades in their daily conversations.

“once we find a specific word for a feeling, that somewhat superficial feeling becomes a precise concept in our mind”

Beyond having the power to influence our color perception, language can also have an impact on how we express our emotions. For example, Uitwaaien is a Dutch word for taking a walk in the wind to clear one’s head. Probably inspired by their windy weather, Dutch people see this as a refreshing activity and even made a word for it. On a more melancholic note, natsukashii, a Japanese word, means feeling a nostalgic longing for the past while also feeling grateful for those memories. It defines the bittersweet feeling of missing the happy memories in our past. This time from German, Sehnsucht is a word to express the intense desire for alternative paths and states of life. Picture the most beautiful sunset you watched, accompanied by the refreshing feeling of crispy weather. Longing to go back to that exact moment, is what German speakers call Sehnsucht. Another word, retrouvailles, is a French word that (literally) means ‘reunion’ in English. However, this word expresses more than a simple reunion. Retrouvailles implies that this reunion is happening with loved ones after a long time of being away from each other, it expresses the powerful joy in that moment.

These feelings are surely familiar to all of us. We all had that incredible moment of retrouvailles, experienced uitwaaien around Amsterdam (probably during lockdown), or felt the natsukashii while thinking about our good memories. But what makes it interesting is that once we find a specific word for a feeling, that somewhat superficial feeling becomes a precise concept in our mind. The now-defined emotion becomes more expressible and its experience gets richer. Imagine not having the word ‘beautiful’, how would we define the people (and the things) we find beautiful? We would still feel it in some way for sure, but how intense would it be? Or imagine not having a specific word for the concept of love; feeling of affection, caring deeply for someone (or something), being supportive, and all the other positive feelings that come to mind when ‘love’ is mentioned. The single word love encompasses it all, gives people a way to define their feelings, express themselves, and even write books and songs about it. Consequently, it enriches the experience of that emotion and makes it more meaningful.

“there are many other worlds to discover by learning new languages”

Besides enriching our experience of emotions, these words also change the way we perceive the world, just as it happens with the color words. Maybe Wittgenstein went a bit far by saying ‘The limits of my language are the limits of my mind. All I know is what I have words for.’ because there is no doubt, we still experience more than what we have words for. Zuñi speakers sure experience orange and yellow, and non-French speakers sure feel joyful seeing their friends after a long time. However, Wittgenstein was still right in a way. Our mind tends to draw our attention towards the concepts and the emotions that we already have words for. It focuses on the aspects of the world that we already know how to define, and the rest goes unnoticed.

Our language shapes our perception. Different languages have different perspectives on the world, and they live in different worlds. When I learned French and finally felt like I mastered it enough to understand their literature, I felt like I was given a key to the world of Montaigne, Camus, and Sartre. I read the translations of their books before but reading them in the same way the writers see the world and the way they define it with their words, was quite different from the translations. This experience made me realize that a translation between two languages is no different than switching between two worlds. No matter how good the translation is, there is always something that gets lost and is missed by foreign readers.

To conclude, the languages we speak have the power to shape the way we experience the world. We can even go as far as to say that languages are powerful enough to create different worlds. This is not to say that our languages limit us, as Wittgenstein put it. Rather, it means that there are many other worlds to discover by learning new languages. I now have enough reasons to learn German to read Zweig and Goethe, or even Russian to read Gogol and Dostoyevsky in their own worlds.<<