The Physical and Psychological Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse & the Current Pandemic Lockdown

Although studies agree with the countless gruesome consequences of childhood sexual abuse, newspapers do not see eye to eye on how much the current pandemic affects cases of domestic sexual abuse. But, they do seem to agree on the fact that an abused child is changed forever. In this article, I raise the topic of childhood sexual abuse by first discussing physical and psychological consequences of the abuse and later on combine it with a perspective from the current pandemic-situation.

The Physical and Psychological Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse & the Current Pandemic Lockdown

Although studies agree with the countless gruesome consequences of childhood sexual abuse, newspapers do not see eye to eye on how much the current pandemic affects cases of domestic sexual abuse. But, they do seem to agree on the fact that an abused child is changed forever. In this article, I raise the topic of childhood sexual abuse by first discussing physical and psychological consequences of the abuse and later on combine it with a perspective from the current pandemic-situation.

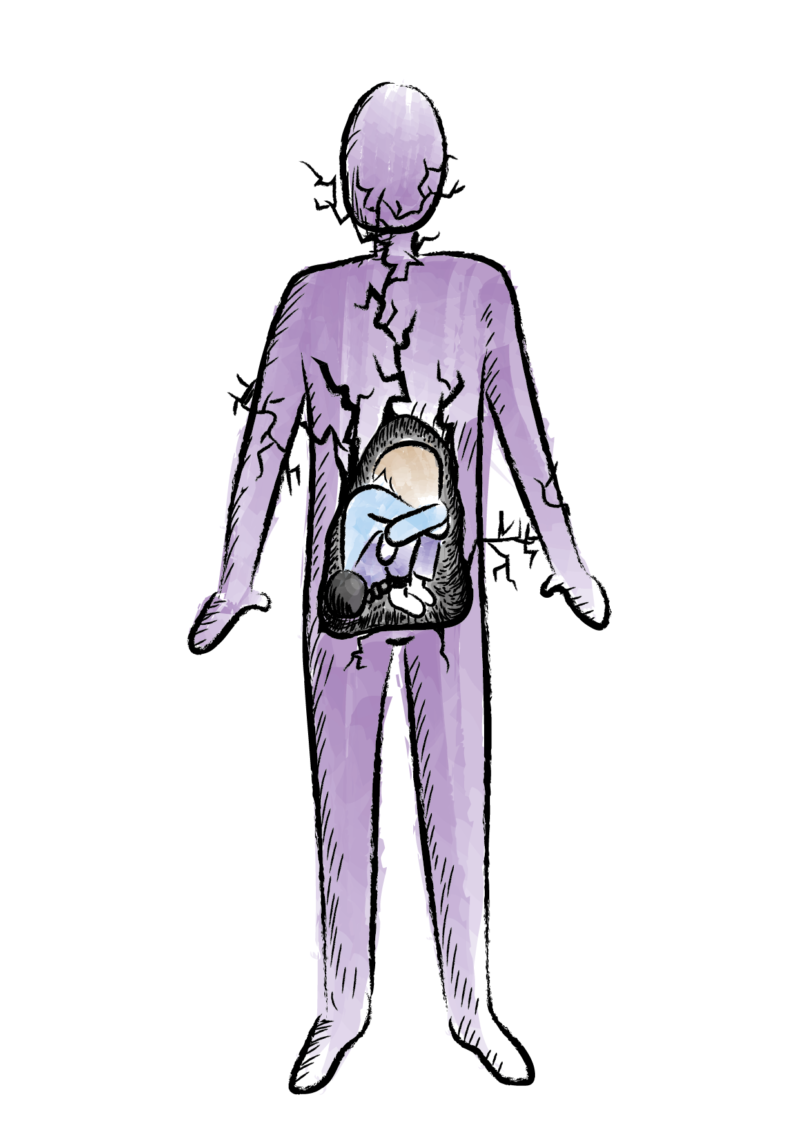

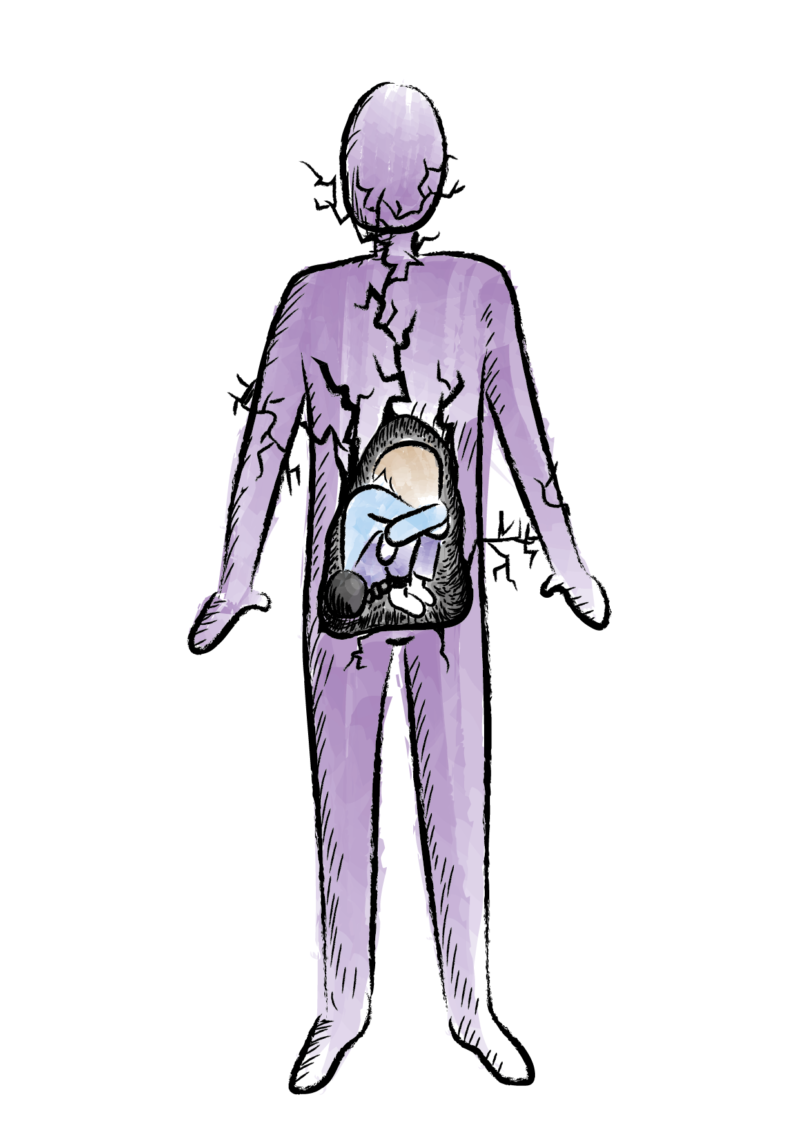

Illustration: Chitra Mohanlal

As a parent, you have the crucial role to provide a safe, warm and caring environment for your child. Fortunately, for many children this is a situation that comes naturally. However, there is a less fortunate group of children that has to go through early child adversities such as physical, sexual or emotional abuse in a place where they should feel the safest: at home. These phenomena have gruesome consequences. Considering the current pandemic, one might think of the danger of the increased stay-at-home time of both parents and children. Are the children living in a violent home more at risk nowadays and has domestic child sexual abuse increased in these pandemic-months? Sexual abuse is one form of child abuse that involves a child being used for sexual stimulation by an adult or older child (The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry., 2020). It often includes body contact, inappropriate touching and genital exposure. Sexual abuse frequently happens within family or with someone the child knows well, like an aquaintance or neighbour. This can deter the child from talking about the abuse.

I would like to start with a question that many would wonder about when reading about domestic sexual abuse: why? Why would you treat your own child whom you are almost evolutionary forced to love unconditionally, in such an inhumane way? The question still stands when the abuse is being done to another child, how is one capable of treating a child that way? A common explanation is that victimized children grow up to victimize others: the abused one becomes the abuser. The cycle of violence theory, suggesting that victims of child maltreatment are at high risk for offending, has received considerable support from prospective investigations (Brezina, 1998; Kakar, 1996; Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Thornberry et al., 2001; Widom, 1989a; Widom & Maxfield, 2001; Zingraff et al., 1993). Brezina (1998) proposed that childhood maltreatment is associated with delinquency, whereas Widom and & Maxfield (2001) found similar results: childhood abuse and neglect increased the odds of future delinquency and adult criminality by 29 percent. Despite only explaining a small tip of the iceberg which doesn’t even begin to cover all the possible causes of child abuse, the cycle of violence is an interesting theory worth mentioning.

The importance of raising the topic of sexual abuse is shown in a study from 1996. It was found that abused adults are twice as likely to suffer from mental health disorders when compared to adults who have not been abused (George, 1996). Furthermore, another study drew the conclusion that child abuse survivors report more somatic symptoms than those who have not been abused (Newman et al., 2000). These somatic symptoms include headaches, sinus pain, muscle pain, and more. Strong support has been found for relationships between childhood sexual abuse, self-esteem, depression and suicidal behaviour. Freshwater, Leach, and Aldridge (2001) concluded that women who have been sexually abused as children have lower self-esteem. Moreover, patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse are at higher risk for psychiatric morbidity and even prolonged depression (Zlotnick, Mattia, & Zimmerman, 2001). This higher prevalence of depression has been confirmed by other researchers, and more studies have been conducted regarding suicidal behaviour. Bridgeland et al. (2001) collected data of college students and found a strong positive correlation between childhood abuse and attempted suicide. In conclusion, a history of childhood sexual abuse significanlty correlates with lower self-esteem, prolonged depression and even attempted suicide.

“Traumatic experiences – such as childhood sexual abuse – have the power to affect the physiology of the developing brain”

Lastly, in the category of psychological consequences, I will discuss post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is characterized by sudden intrusive memories of the original traumatic experience and a wave of the remembered emotional response (Wilson, 2007). Rodriguez, Ryan, Rowan, and Foy (1999) conducted a study with 117 adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. They concluded that as much as 86 percent met DSM-III-R criteria for a PTSD diagnosis at some point during their lives. Not only was this high amount of survivors vulnerable for PTSD, the duration and severity of the abuse were directly correlated with the severity and variance in PTSD symptoms (Rodriguez, et al., 1999).

Now that we have discussed psychological consequences, the next paragraphs will introduce mere physical symptoms that associate with childhood sexual abuse. It is intriguing to know that traumatic experiences – such as childhood sexual abuse – have the power to affect the physiology of the developing brain (Heim et al., 2002). The abuse is associated with chronic hyperarousal of the stress response and alertness to the environment, making survivors extra vulnerable to stress. This vulnerability may lead to increased reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis in the brain (Heim et al., 2002; Stein, Yehuda, & Koverola, 1997), which is linked to suppression of immune functioning and has undesirable health consequences (Altemus, Cloitre, & Dhabhar, 2003; Anda et al., 2006; SachsEricsson et al., 2005). In relation to PTSD, it was even investigated whether adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse would have HPA axis abnormalities similar to those of combatrelated PTSD. A blood measurement indicated that participants with a history of childhood sexual abuse showed low bloodserum cortisol levels similar to those of combat-related PTSD. Also, it is found that a history of childhood sexual abuse is associated with the incidence of physiological conditions such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Fibromyalgia is a disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, that is described as a dull constant ache that lasts at least three months (Mayo Clinic, 2020). It is associated with childhood sexual abuse and the relationship increases in strength when the abuse is more pervasive, invasive, or traumatic (Walker et al., 1997). Furthermore, women with IBS reported a higher relative incidence of childhood sexual abuse (Heitkemper et al., 2001), where IBS is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habit (Mayo Clinic, 2020). Aside from physical and psychological health issues, childhood sexual abuse also leaves a footprint on academical achievement. Duncan (2000) posited that survivors of childhood sexual abuse are significantly more likely to drop out of college than non-abused students. The researcher concluded that adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse are less likely to succeed in academia.

“Abusers have ‘free rein’ now that children are more often home”

AD

Now that the associative harmful consequences of childhood sexual abuse have been discussed, it has become clear that it is important to prevent the growth of abusive situations as much as possible. But what role does the COVID-19 crisis play? That leads us to the question whether domestic sexual abuse has increased during the current pandemic situation. Various Dutch newspapers write contradicting conclusions: AD claims that abusers have ‘free rein’ now that children are more often home, whereas NU.nl concludes that the numbers of domestic childabuse are not rising (Van Kampen, 2020; NU.nl, 2020). However, one should take into account the difficulty of measuring cases of abuse as it happens behind closed doors. A recent study in Nepal was done and showed increased reported cases of child sexual abuse during the COVID-19 lockdown (Dahal, Khanal, Maharjan, Panthi, & Nepal, 2020). In addition, it is not unreasonable to assume that talking about the sexual abuse to an adult becomes more difficult when the child sees fewer adults during the day due to lockdown. Lastly, conclusions of previously described studies stated that not only the severity, but also the duration of the abuse directly correlates with severity in subsequent symptoms. Despite the relationship being correlational as opposed to causal, it is still important to take into account that due to the pandemic lockdown, the severity and duration of sexual abuse might rise and that it has a probability of leading to more extreme outcomes.

This article first explored consequences correlated with sexual childhood abuse: depressive and suicidal symptoms, PTSD diagnoses, somatic symptoms like fibromyalgia, and many more. This showed the enormous impact childhood sexual abuse might have later in life. Thereafter, the current pandemic lockdown has been taken into account when reading and analysing these potential consequences. It can be concluded that the previous mentioned correlated symptoms, show the importance of decreasing the cases of sexual abuse as much as possible, especially now that families are living more ‘private’. This is of crucial importance: because a sexually abused child is – indeed – forever changed. <<

References

– Altemus, M., Cloitre, M., & Dhabhar, F. S. (2003). Enhanced cellular immune response in women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(9), 1705–1707.Retrieved from http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org.ezp.waldenulibrary.org/ cgi/reprint/160/9/1705

– Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and ClinicalNeuroscience, 256(3), 174.

– Brezina, T., (1998). Adolescent Maltreatment and Delinquency: The Question of Intervening Processes. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35(1), 71–99.

– Bridgeland, W. M., Duane, E. D., & Stewart, C. S. (2001). Victimization and attempted suicide among college students. College Student Journal, 35(1), 63–77.

– Dahal, M., Khanal, P., Maharjan, S., Panthi, B., & Nepal, S. (2020). Mitigating violence against women and young girls during COVID-19 induced lockdown in Nepal: a wake-up call. Globalization and health, 16(1), 1-3.

– Duncan, R. D. (2000). Childhood maltreatment and college drop-out rates: Implications for child abuse researchers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(9), 987–996.

– Freshwater, K., Leach, C., & Aldridge, J. (2001). Personal constructs, childhood sexual abuse and revictimization. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74, 379–397.

– George, M. (1996). Listening and hearing: Child sex abuse. Nursing Standard, 10(30), 22–23

– Heim, C., Newport, J., Wagner, D., Wilcox, M. M., Miller, A. H., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2002). The role of early adverse experience and adulthood stress in the prediction of neuroendocrine stress reactivity in women: A multiple regression analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 15(12), 117–125.

– Heitkemper, M., Jarret, M., Taylor, P., Walker, E., Landerburger, K., & Bond, E. F. (2001). Effects of sexual and physical abuse on symptom experiences in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Nursing Research, 50(1), 15–23.

– Kakar, S. (1996). The colors of violence: Cultural identities, religion, and conflict. University of Chicago Press.

– Kindermishandeling. (2020). politie.nl. Retrieved from: https://www.politie.nl/themas/kindermishandeling.html

– Mayo Clinic Staff. (2020, 7 oktober). Fibromyalgia – Symptoms and causes. Mayoclinic.org. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fibromyalgia/symptoms-causes/syc-203547

– Newman, M. G., Clayton, L., Zuellig, A., Cashman, L., Arnow, B., Dea, R., et al. (2000). The relationships of childhood sexual abuse and depression with somatic symptoms and medical utilization. Psychological Medicine, 30, 1063–1077.

– NU.nl. (2020, 15 april). Jeugdzorg ziet aantal meldingen over kindermishandeling niet toenemen. NU. Retrieved from: https://www.nu.nl/coronavirus/6044918/jeugdzorg-ziet-aantal-meldingen-over-kindermishaneling-niet-toenemen.html

– Rodriguez, N., Ryan, S., Rowan, A. B., & Foy, D. W. (1999). Posttraumatic stress disorder in a clinical sample of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20(10), 943–952.

– Smith, C., & Thornberry, T. P. (1995). The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology, 33(4), 451-481.

– Stein, M. B., Yehuda, R., & Koverola, C. (1997). Enhanced dexamethasone suppression of plasma cortisol in adult women traumatized by childhood sexual abuse. Biological Psychiatry, 42(8),680–686.

– The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (2020, mei). Sexual Abuse. aacap.org. Retrieved from http://www.aacap.org

– The role of lifestyle-related treatments for IBS – Mayo Clinic. (2017, 28 maart). mayoclinic.org. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/digestive-diseases/news/the-role-of-lifestyl-related-treatments-for-ibs/mac-20431272

–Thornberry, T. P., Ireland, T. O., & Smith, C. A. (2001). The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and psychopathology, 13(4), 957-979.

– Van Kampen, M. (2020, 5 mei). Kindermishandeling in tijden van corona: ‘Dader heeft vrij spel’. Retrieved from www.ad.nl.

– Walker, E. A., Keegan, D., Gardner, G., Sullivan, M., Bernstein, D., & Katon, E. J. (1997). Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: II. Sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and neglect. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59(5), 572–577.

– Widom, C. S. (1989). Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(3), 355-367.

– Widom, C. S., & Maxfield, M. G. (2001). An Update on the” Cycle of Violence.” Research in Brief.

– Wilson, D. R. (2007). Memory repression in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Community and Health Sciences, 2(2), 72–83.

– Zingraff, M. T., Leiter, J., Myers, K. A., & Johnsen, M. C. (1993). Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology, 31(2), 173-202.

– Zlotnick, C., Mattia, J., & Zimmerman, M. (2001). Clinical features of survivors of sexual abuse with major depression. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 357–367.

As a parent, you have the crucial role to provide a safe, warm and caring environment for your child. Fortunately, for many children this is a situation that comes naturally. However, there is a less fortunate group of children that has to go through early child adversities such as physical, sexual or emotional abuse in a place where they should feel the safest: at home. These phenomena have gruesome consequences. Considering the current pandemic, one might think of the danger of the increased stay-at-home time of both parents and children. Are the children living in a violent home more at risk nowadays and has domestic child sexual abuse increased in these pandemic-months? Sexual abuse is one form of child abuse that involves a child being used for sexual stimulation by an adult or older child (The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry., 2020). It often includes body contact, inappropriate touching and genital exposure. Sexual abuse frequently happens within family or with someone the child knows well, like an aquaintance or neighbour. This can deter the child from talking about the abuse.

I would like to start with a question that many would wonder about when reading about domestic sexual abuse: why? Why would you treat your own child whom you are almost evolutionary forced to love unconditionally, in such an inhumane way? The question still stands when the abuse is being done to another child, how is one capable of treating a child that way? A common explanation is that victimized children grow up to victimize others: the abused one becomes the abuser. The cycle of violence theory, suggesting that victims of child maltreatment are at high risk for offending, has received considerable support from prospective investigations (Brezina, 1998; Kakar, 1996; Smith & Thornberry, 1995; Thornberry et al., 2001; Widom, 1989a; Widom & Maxfield, 2001; Zingraff et al., 1993). Brezina (1998) proposed that childhood maltreatment is associated with delinquency, whereas Widom and & Maxfield (2001) found similar results: childhood abuse and neglect increased the odds of future delinquency and adult criminality by 29 percent. Despite only explaining a small tip of the iceberg which doesn’t even begin to cover all the possible causes of child abuse, the cycle of violence is an interesting theory worth mentioning.

The importance of raising the topic of sexual abuse is shown in a study from 1996. It was found that abused adults are twice as likely to suffer from mental health disorders when compared to adults who have not been abused (George, 1996). Furthermore, another study drew the conclusion that child abuse survivors report more somatic symptoms than those who have not been abused (Newman et al., 2000). These somatic symptoms include headaches, sinus pain, muscle pain, and more. Strong support has been found for relationships between childhood sexual abuse, self-esteem, depression and suicidal behaviour. Freshwater, Leach, and Aldridge (2001) concluded that women who have been sexually abused as children have lower self-esteem. Moreover, patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse are at higher risk for psychiatric morbidity and even prolonged depression (Zlotnick, Mattia, & Zimmerman, 2001). This higher prevalence of depression has been confirmed by other researchers, and more studies have been conducted regarding suicidal behaviour. Bridgeland et al. (2001) collected data of college students and found a strong positive correlation between childhood abuse and attempted suicide. In conclusion, a history of childhood sexual abuse significanlty correlates with lower self-esteem, prolonged depression and even attempted suicide.

“Traumatic experiences – such as childhood sexual abuse – have the power to affect the physiology of the developing brain”

Lastly, in the category of psychological consequences, I will discuss post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is characterized by sudden intrusive memories of the original traumatic experience and a wave of the remembered emotional response (Wilson, 2007). Rodriguez, Ryan, Rowan, and Foy (1999) conducted a study with 117 adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. They concluded that as much as 86 percent met DSM-III-R criteria for a PTSD diagnosis at some point during their lives. Not only was this high amount of survivors vulnerable for PTSD, the duration and severity of the abuse were directly correlated with the severity and variance in PTSD symptoms (Rodriguez, et al., 1999).

Now that we have discussed psychological consequences, the next paragraphs will introduce mere physical symptoms that associate with childhood sexual abuse. It is intriguing to know that traumatic experiences – such as childhood sexual abuse – have the power to affect the physiology of the developing brain (Heim et al., 2002). The abuse is associated with chronic hyperarousal of the stress response and alertness to the environment, making survivors extra vulnerable to stress. This vulnerability may lead to increased reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis in the brain (Heim et al., 2002; Stein, Yehuda, & Koverola, 1997), which is linked to suppression of immune functioning and has undesirable health consequences (Altemus, Cloitre, & Dhabhar, 2003; Anda et al., 2006; SachsEricsson et al., 2005). In relation to PTSD, it was even investigated whether adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse would have HPA axis abnormalities similar to those of combatrelated PTSD. A blood measurement indicated that participants with a history of childhood sexual abuse showed low bloodserum cortisol levels similar to those of combat-related PTSD. Also, it is found that a history of childhood sexual abuse is associated with the incidence of physiological conditions such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Fibromyalgia is a disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, that is described as a dull constant ache that lasts at least three months (Mayo Clinic, 2020). It is associated with childhood sexual abuse and the relationship increases in strength when the abuse is more pervasive, invasive, or traumatic (Walker et al., 1997). Furthermore, women with IBS reported a higher relative incidence of childhood sexual abuse (Heitkemper et al., 2001), where IBS is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habit (Mayo Clinic, 2020). Aside from physical and psychological health issues, childhood sexual abuse also leaves a footprint on academical achievement. Duncan (2000) posited that survivors of childhood sexual abuse are significantly more likely to drop out of college than non-abused students. The researcher concluded that adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse are less likely to succeed in academia.

“Abusers have ‘free rein’ now that children are more often home”

AD

Now that the associative harmful consequences of childhood sexual abuse have been discussed, it has become clear that it is important to prevent the growth of abusive situations as much as possible. But what role does the COVID-19 crisis play? That leads us to the question whether domestic sexual abuse has increased during the current pandemic situation. Various Dutch newspapers write contradicting conclusions: AD claims that abusers have ‘free rein’ now that children are more often home, whereas NU.nl concludes that the numbers of domestic childabuse are not rising (Van Kampen, 2020; NU.nl, 2020). However, one should take into account the difficulty of measuring cases of abuse as it happens behind closed doors. A recent study in Nepal was done and showed increased reported cases of child sexual abuse during the COVID-19 lockdown (Dahal, Khanal, Maharjan, Panthi, & Nepal, 2020). In addition, it is not unreasonable to assume that talking about the sexual abuse to an adult becomes more difficult when the child sees fewer adults during the day due to lockdown. Lastly, conclusions of previously described studies stated that not only the severity, but also the duration of the abuse directly correlates with severity in subsequent symptoms. Despite the relationship being correlational as opposed to causal, it is still important to take into account that due to the pandemic lockdown, the severity and duration of sexual abuse might rise and that it has a probability of leading to more extreme outcomes.

This article first explored consequences correlated with sexual childhood abuse: depressive and suicidal symptoms, PTSD diagnoses, somatic symptoms like fibromyalgia, and many more. This showed the enormous impact childhood sexual abuse might have later in life. Thereafter, the current pandemic lockdown has been taken into account when reading and analysing these potential consequences. It can be concluded that the previous mentioned correlated symptoms, show the importance of decreasing the cases of sexual abuse as much as possible, especially now that families are living more ‘private’. This is of crucial importance: because a sexually abused child is – indeed – forever changed. <<