Most of the world’s knowledge is at your fingertips with a simple word command in a search engine and internet connection. Having this power doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that researching a topic for a limited amount of time makes you an expert. Your confidence in your own understanding of something may not be justified, and the Dunning-Kruger Effect reveals that you aren’t alone in making this misjudgment.

Most of the world’s knowledge is at your fingertips with a simple word command in a search engine and internet connection. Having this power doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that researching a topic for a limited amount of time makes you an expert. Your confidence in your own understanding of something may not be justified, and the Dunning-Kruger Effect reveals that you aren’t alone in making this misjudgment.

Illustration: Carolien de Bruin

People are cognitive misers… We fall prey to many cognitive biases that make reality very subjective and obscure what is truly going on. Cognitive biases are errors in thinking as the brain attempts to make sense of the world and simplify it. There are some that may be a little more known than others – especially to psychology students – such as the confirmation bias. It explains how people tend to look for information that confirms their view and disregard information that goes against it. The way people interact with available knowledge might, however, be more skewed than expected.

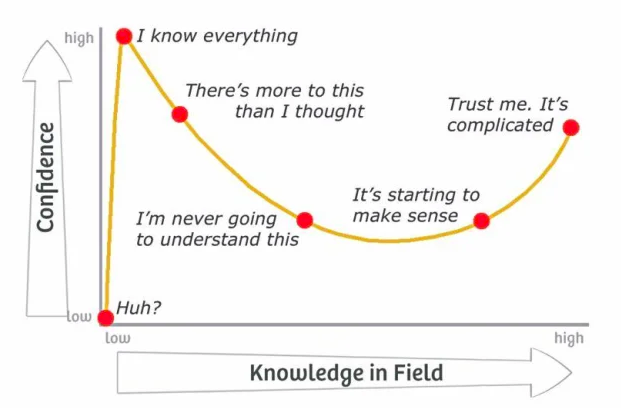

This is where the Dunning-Kruger effect comes in. It was first described in the joint study titled “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” by David Dunning and Justing Kruger (1999). The effect was investigated across four studies focused on humour, logical reasoning, and grammar. The participants were assessed on their abilities in the domains and asked to evaluate their competence level. The results showed that those who scored in the lower quartile for ability would significantly overestimate their ability in comparison to others, from the 12th percentile to 62nd percentile respectively.

The Dunning-Kruger effect was based on the study which describes the tendency for individuals with little knowledge of a topic or skill to overestimate their own understanding. However, the more one learns, the less confident they become as they gain metacognition to see the gap between their own knowledge and the knowledge in the field overall. This bias closely relates to another bias called the illusory superiority effect, where individuals overestimate their positive attributes and abilities, which makes them feel like they are better than average in relation to other individuals. Only the very experts who know the most are confident in what they know, but they are capable of acknowledging the complexity of the topic.

Image courtesy of Idrees Dargahwala

This is not the first time that such a bias was considered. There are a series of philosophers and writers who commented on this human tendency. In the words of the 6th century BCE Chinese philosopher Confucius, ‘To know what you know and to know what you don’t know, that is true knowledge.’ Greek philosopher Socrates is said to have commented ‘The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.’ And more recently, in the words of world-famous writer Shakespeare, ‘The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.’ It’s clear that the inspiration of the Dunning-Kruger effect has been around for quite some time.

In light of Charles Darwin’s comment ‘Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.’ (1876), the confidence factor in the Dunning-Kruger effect is very apparent. Not to say that everyone who is confident in their opinion is necessarily ignorant, but confidence can be very convincing, even when the individual may be wrong. This is quite dangerous, especially when taking into consideration that everyone can act confident in their opinions. If we take a contemporary example – from my perspective – the President of the United States Donald Trump has been quite an interesting subject to illustrate the Dunning-Kruger effect. His frequent proclamation of knowing everything about a given field (for a short compilation, click here) makes it apparent that either he uses his confidence as a persuasion technique, or fully holds a superior view of his abilities without possessing the metacognition to acknowledge that he may not have all the information.

In terms of how one can see this effect taking place on a day to day basis, the effect seems to play a role in contemporary discourse online. Not only does it give us the opportunity to learn about almost anything, but sharing opinions with others is the next best thing. Various platforms, like Twitter, allow for open discussions on any possible topic, whether that’s on politics, science, or the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently some sceptic groups have risen in the media, such as flat-earthers who aren’t convinced of the earth’s spherical form, anti-vaxxers, who are doubtful of the validity of vaccines, or those convinced that 5g towers are behind the spread of COVID-19. These groups are calling into question scientifically supported concepts, bringing their own supposed facts into the equation, and one has to wonder if confident misinformation is the driver of the conversation, rather than healthy scepticism. Furthermore, on the topic of online forums, this effect can be amplified through selective interaction with people who agree with your opinion. The concept of echo chambers comes to mind, which describes spaces where individuals communicate only with people who already agree with their opinions on a given topic. Having such support from a group of strangers can feel satisfying, but that positive reinforcement for possibly erroneous ideas can quickly escalate into an unsound view of the world.

“It is mindful to contemplate the null hypothesis of any complex situation, as that may be the reality.”

So how do we make sure to minimize this effect in ourselves? Taking notes from an interview with David Dunning (2019), an important sentiment that comes from the effect is self-reflection. Check your assumptions, think about the reason why your opinion on a given topic is the way it is, and don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know something. He also brings to the attention that a lot of the erroneous judgments we make come from learning all by ourselves. Being open-minded and consulting with others allows you to expand your understanding of other perspectives and open your eyes to the complexity of any given topic (Resnick, 2019). In practical terms, it is mindful to contemplate the null hypothesis of any complex situation, as that may be the reality. And as the law of parsimony states, otherwise also known as Occam’s razor, from all the possible explanations for a given event, the simplest one is most likely to be the accurate one.

In some ways, you can also observe counteractions against the effect in any strong psychology research paper. As a psychologist carrying out and reporting on research, as much as confidence in one’s ideas is healthy, being objective about the strengths and limitations is important. Chances are that you may have carried out your own research and were instructed to focus on the details of other studies, your own study, and the overall topic in order to critically evaluate its characteristics. The process itself might feel tedious, however, it is a key component in healthy scientific development. It takes into account the reality that we cannot ever be completely certain about something, and acknowledge that there may always be a confounding variable, a coincidence, or even an error in procedure at play. Applying and consuming such reflective practices in the scientific literature can be a possible guide on how to approach one’s own sense of knowledge; be aware of your strengths and shortcomings.

“It might be wise to be the ones to listen first before trying to make our own voices heard.”

In everyday life, it is difficult to be aware of one’s blind spots and biases. Even knowing about this effect in daily life may not drastically change the way we interact with others because sharing what we’ve learned is something very human, and no one can become an expert in all fields of knowledge. It’s more applicable to adjust the way in which you communicate your beliefs and opinions; with an open mind that you may not have the full picture and you stand to gain from discourse with others and further learning. This is especially apparent, at least in my case, when it comes to the Black Lives Matter movement. A lot of information has been coming out about this issue during this year, and it has been abundantly clear that most of us such as I, who are aren’t directly affected, don’t know the half of it when it comes to the hardships and discrimination that occurs to the Black community. We might be well meaning in contributing to online discourse or public support, but before we start putting our own opinions out there, it might be wise to be the ones to listen first before trying to make our own voices heard.

Given all the unknowns there are in all fields of study, especially psychology, people shouldn’t feel discouraged to learn more. They should, however, be wary of their confidence when it comes to discovering a new topic, as chances are that you don’t have the full picture yet. In the words of German-American poet and writer Charles Bukowski, ‘The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence. The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts.’ However, as a student writing this article, I feel to be in an uncomfortable situation; who am I to preach about checking your biases? Or can I even truly do this topic justice? This effect has made me aware of the fact that although I may have researched the topic for this article, I may not understand the whole scope of it and so, who am I to write about it, or comment on other people’s behaviour? At the same time, I will most likely never know everything there is to know about a given topic to be fully certain that my opinion is fully correct, but as long as I remain aware of my personal limitations and phrase my opinions carefully, hopefully I won’t as easily fall prey to such cognitive biases.

References

– BrainyMedia Inc, 2020. Confucius Quotes. Retrieved from https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/confucius_141560

– BrainyMedia Inc, 2020. Socrates Quotes. Retrieved from https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/socrates_101212

– Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man. London: John Murray.

– Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 77, no. 6, 1999, pp. 1121–1134.

– Resnick, B. An Expert on Human Blind Spots Gives Advice on How to Think. Retrieved from www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/1/31/18200497/dunning-kruger-effect-explain

– Shakespeare, W. (1603). As You Like It. Spark Notes, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.sparknotes.com/nofear/shakespeare/asyoulikeit/page_206/

People are cognitive misers… We fall prey to many cognitive biases that make reality very subjective and obscure what is truly going on. Cognitive biases are errors in thinking as the brain attempts to make sense of the world and simplify it. There are some that may be a little more known than others – especially to psychology students – such as the confirmation bias. It explains how people tend to look for information that confirms their view and disregard information that goes against it. The way people interact with available knowledge might, however, be more skewed than expected.

This is where the Dunning-Kruger effect comes in. It was first described in the joint study titled “Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments.” by David Dunning and Justing Kruger (1999). The effect was investigated across four studies focused on humour, logical reasoning, and grammar. The participants were assessed on their abilities in the domains and asked to evaluate their competence level. The results showed that those who scored in the lower quartile for ability would significantly overestimate their ability in comparison to others, from the 12th percentile to 62nd percentile respectively.

The Dunning-Kruger effect was based on the study which describes the tendency for individuals with little knowledge of a topic or skill to overestimate their own understanding. However, the more one learns, the less confident they become as they gain metacognition to see the gap between their own knowledge and the knowledge in the field overall. This bias closely relates to another bias called the illusory superiority effect, where individuals overestimate their positive attributes and abilities, which makes them feel like they are better than average in relation to other individuals. Only the very experts who know the most are confident in what they know, but they are capable of acknowledging the complexity of the topic.

Image courtesy of Idrees Dargahwala

This is not the first time that such a bias was considered. There are a series of philosophers and writers who commented on this human tendency. In the words of the 6th century BCE Chinese philosopher Confucius, ‘To know what you know and to know what you don’t know, that is true knowledge.’ Greek philosopher Socrates is said to have commented ‘The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.’ And more recently, in the words of world-famous writer Shakespeare, ‘The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.’ It’s clear that the inspiration of the Dunning-Kruger effect has been around for quite some time.

In light of Charles Darwin’s comment ‘Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.’ (1876), the confidence factor in the Dunning-Kruger effect is very apparent. Not to say that everyone who is confident in their opinion is necessarily ignorant, but confidence can be very convincing, even when the individual may be wrong. This is quite dangerous, especially when taking into consideration that everyone can act confident in their opinions. If we take a contemporary example – from my perspective – the President of the United States Donald Trump has been quite an interesting subject to illustrate the Dunning-Kruger effect. His frequent proclamation of knowing everything about a given field (for a short compilation, click here) makes it apparent that either he uses his confidence as a persuasion technique, or fully holds a superior view of his abilities without possessing the metacognition to acknowledge that he may not have all the information.

In terms of how one can see this effect taking place on a day to day basis, the effect seems to play a role in contemporary discourse online. Not only does it give us the opportunity to learn about almost anything, but sharing opinions with others is the next best thing. Various platforms, like Twitter, allow for open discussions on any possible topic, whether that’s on politics, science, or the COVID-19 pandemic. Recently some sceptic groups have risen in the media, such as flat-earthers who aren’t convinced of the earth’s spherical form, anti-vaxxers, who are doubtful of the validity of vaccines, or those convinced that 5g towers are behind the spread of COVID-19. These groups are calling into question scientifically supported concepts, bringing their own supposed facts into the equation, and one has to wonder if confident misinformation is the driver of the conversation, rather than healthy scepticism. Furthermore, on the topic of online forums, this effect can be amplified through selective interaction with people who agree with your opinion. The concept of echo chambers comes to mind, which describes spaces where individuals communicate only with people who already agree with their opinions on a given topic. Having such support from a group of strangers can feel satisfying, but that positive reinforcement for possibly erroneous ideas can quickly escalate into an unsound view of the world.

“It is mindful to contemplate the null hypothesis of any complex situation, as that may be the reality.”

So how do we make sure to minimize this effect in ourselves? Taking notes from an interview with David Dunning (2019), an important sentiment that comes from the effect is self-reflection. Check your assumptions, think about the reason why your opinion on a given topic is the way it is, and don’t be afraid to admit that you don’t know something. He also brings to the attention that a lot of the erroneous judgments we make come from learning all by ourselves. Being open-minded and consulting with others allows you to expand your understanding of other perspectives and open your eyes to the complexity of any given topic (Resnick, 2019). In practical terms, it is mindful to contemplate the null hypothesis of any complex situation, as that may be the reality. And as the law of parsimony states, otherwise also known as Occam’s razor, from all the possible explanations for a given event, the simplest one is most likely to be the accurate one.

In some ways, you can also observe counteractions against the effect in any strong psychology research paper. As a psychologist carrying out and reporting on research, as much as confidence in one’s ideas is healthy, being objective about the strengths and limitations is important. Chances are that you may have carried out your own research and were instructed to focus on the details of other studies, your own study, and the overall topic in order to critically evaluate its characteristics. The process itself might feel tedious, however, it is a key component in healthy scientific development. It takes into account the reality that we cannot ever be completely certain about something, and acknowledge that there may always be a confounding variable, a coincidence, or even an error in procedure at play. Applying and consuming such reflective practices in the scientific literature can be a possible guide on how to approach one’s own sense of knowledge; be aware of your strengths and shortcomings.

“It might be wise to be the ones to listen first before trying to make our own voices heard.”

In everyday life, it is difficult to be aware of one’s blind spots and biases. Even knowing about this effect in daily life may not drastically change the way we interact with others because sharing what we’ve learned is something very human, and no one can become an expert in all fields of knowledge. It’s more applicable to adjust the way in which you communicate your beliefs and opinions; with an open mind that you may not have the full picture and you stand to gain from discourse with others and further learning. This is especially apparent, at least in my case, when it comes to the Black Lives Matter movement. A lot of information has been coming out about this issue during this year, and it has been abundantly clear that most of us such as I, who are aren’t directly affected, don’t know the half of it when it comes to the hardships and discrimination that occurs to the Black community. We might be well meaning in contributing to online discourse or public support, but before we start putting our own opinions out there, it might be wise to be the ones to listen first before trying to make our own voices heard.

Given all the unknowns there are in all fields of study, especially psychology, people shouldn’t feel discouraged to learn more. They should, however, be wary of their confidence when it comes to discovering a new topic, as chances are that you don’t have the full picture yet. In the words of German-American poet and writer Charles Bukowski, ‘The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence. The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts.’ However, as a student writing this article, I feel to be in an uncomfortable situation; who am I to preach about checking your biases? Or can I even truly do this topic justice? This effect has made me aware of the fact that although I may have researched the topic for this article, I may not understand the whole scope of it and so, who am I to write about it, or comment on other people’s behaviour? At the same time, I will most likely never know everything there is to know about a given topic to be fully certain that my opinion is fully correct, but as long as I remain aware of my personal limitations and phrase my opinions carefully, hopefully I won’t as easily fall prey to such cognitive biases.